The Hanged Man: Part 9: Lughnasadh

Post #88: In which travelers meet and seek a resting place ...

(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of The Hanged Man. For the next serial post, go here. If you prefer to read Part 9 in its entirety, go here.)

CHAPTER 32

HEKS

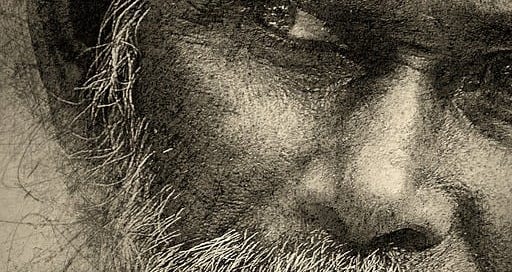

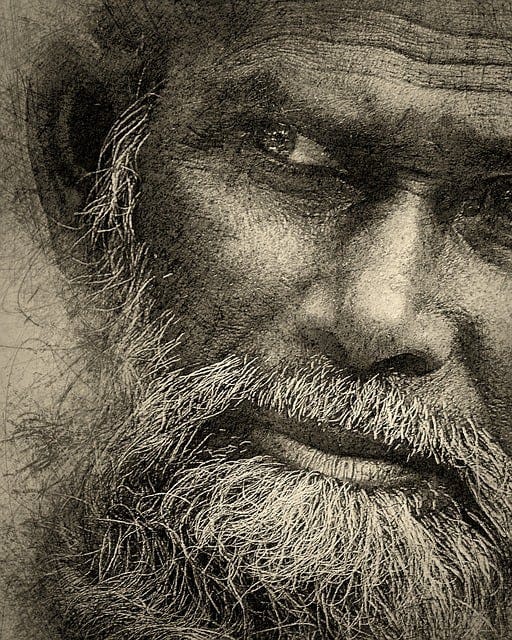

Heks watched Gabriel.

He was a spry old man in spite of his cane, curious, friendly and occasionally acerbic. Juliana’s death had done him a lot of good. He’d been sinking into dotage, bored, lonely and just a tinge bitter, when Dar and Radulf appeared. Now life was full of interest, even adventure. He had new people to talk to, new ideas to think about, and he once again felt part of something vital.

He talked to everyone, all the time. No one escaped his questions or his bright-eyed observation. He had a disconcerting habit of seeing and speaking bald truths, having no patience for indirection.

Toward Heks he demonstrated a mixture of curiosity and restraint. They were the same age. She knew he’d possessed a family — once. She found his reticence on the subject remarkable, given his general garrulousness. She didn’t probe, having plenty of her own past she preferred to keep private.

She was aware of his interest in her. A lifetime ago she’d been young and reasonably attractive. Well…young at least. As midwife and healer, she’d known many people, many families, and she’d received her share of surreptitious pats and admiring looks and even a kiss or two… Then Joe came along and swept through her life like an ice storm in spring, glittering and brilliant for an hour, but converting bud, blossom and leaf into wet black decay that turned to slime with a touch.

Gabriel’s interest in her was friendly, no more. He led her on to talk and spent hours walking with her or perched in a cart next to her. He generally ate with her and slept near her. She could see the others gradually accepting them as a pair. He was gentle with her, pretending not to see her reflexive cringe or flinch where there was an unexpected noise or motion. She was certain he’d never hurt her physically. He was a good man.

She thought sourly, I’m certainly trying hard to persuade myself!

The truth was, she, sere, wrinkled, thin-haired and withered, wanted passion, or romance, or one of those shameful words describing what can happen between a man and a woman. A young man and woman. Touch that made fine hairs stand up, scent, texture of hair and skin. She wanted to feel her face cupped in hands just a little too hard, a little too insistent, feel her lip caught between teeth, feel her body respond. She wanted to feel a hard knee between her thighs, nudging them inexorably apart…

And then what? she mocked herself. Then scrabble for oil because I’m old and dry?

“No,” said her heart. “Then he reaches for oil and touches you, caresses you, fingers and opens you until your body remembers and believes and responds. And then you know it’s not too late. It can still happen.”

But that was fantasy, secret and pathetic. In the real world, she was an aging, used-up woman. Beauty and passion had never been for her. Friendship and companionship, now those were possible. Those were appropriate desires. Even an old woman could hope for a friend. She knew her hands retained their skill. She hadn’t forgotten how to help open the way for new life to be born. She could reasonably dream of kneeling beside the miracle of mother and emerging child again, of being a surrogate grandmother. It had to be enough.

Yet she wanted more. She could do more. Not now, maybe, not yet, but someday. Her old life was gone in a whirlwind of blood and fire. She recognized nothing as hers except, oddly, the shawl she’d taken away from Juliana’s house. Gabriel himself -- no. Nothing in her hungry heart recognized him. She wanted nothing from him except to call him friend.

She stayed with Dar and the villagers, not because of Gabriel, but because of their guide.

No one knew where they were going. They wanted a new place to build a community. It would soon be first harvest, and they needed to find a place to spend the winter. As far as Heks could tell, Dar meant to follow his nose and trust in luck. In the beginning, she wasn’t sure she wanted to cast her lot with theirs. Easier, she thought, to make her way alone, try to find the white light she was to follow.

Then, the night before they left, an unearthly White Stag had come to them, slipping out of the woods like mist at dusk. Dar greeted it with reverence, and told the villagers the stag would guide them. Dar appeared relieved, even happy. Heks wondered if the creature had acted as guide for him before. It had melted away between the trees, glowing like a pearl in starlight, as they settled to sleep.

In the morning, Heks set out with the group, taking only the shawl with her.

MARY

“Where are we going?” Mary wiped a tendril of hair off her cheek for what felt like the hundredth time. It wasn’t noon yet. Her pregnancy increased her body temperature and she always felt hot. Today she felt ungainly and cranky as well. The nubile maiden bearing seeds and letting them fall in a wild mist of blood, milk, urine and sweat who’d lain with another Seed-Bearer under the fecund May moon was gone. Her seed pouches were empty and packed carefully away in her bundle.

A seed had taken root and grew in the dark red lining of her belly, and the primordial horned piper walked beside her in dusty boots, glowing with strength and vitality.

“We’re going to meet a friend of mine.” He glanced sideways at her, his face mischievous. “He’s leading a group to a new community. There’ll be wagons and you can rest. A midwife is among them and she can keep an eye on you.”

“And what about you?” She felt nettled, hating how much she wanted to rest. She could see something amused him about his ‘friend,’ but refused to give him the satisfaction of asking. It was too hot.

“I want to see you off your feet, help my friend and find something to do. I want to begin harvest!”

As he’d said this regularly for the last month, she made no reply. She knew he spilled over with energy and could hardly wait for long days in field and orchard. He’d be a big help to a new community, and, frankly, she’d be glad to take a break from his restless vitality. Though he now began to pour out the honey and milk of his strength, she must keep something back, carefully hoard her energy. Her own harvest still lay some way ahead.

“You’re hot. Shall we stop and rest?”

His quick concern diminished her grouchiness.

“No. It’s a hot day. I feel sweaty and fat.”

“We should meet up with them this evening. What do you say to a plate of food you didn’t have to cook and a comfortable bed?”

“I say, lead me to it.” She felt she should show an interest, ask about his friend and the others with him, but she couldn’t summon the energy.

He took her sweaty hand comfortingly in his.

She thought it was like walking hand in hand with the sun.

***

Five hours later, Mary seethed with fury. The cart was stifling. She felt every bit as hot in its shade as she had in the sun, and it didn’t admit a breath of air. In one more minute she was going to sit up, crawl to the back and put her feet on the ground again. The cloak she glared at swayed mockingly on its hook as the cart rolled along the dusty track.

She’d seen that cloak before. During initiation, the enigmatic peddler Dar led the men to their fire, his cloak rippling like dark water in firelight. Now, in the stuffy light, she realized the cloak wasn’t black, but a deep purple. Lugh’s cloak was sewn with gold and copper, ivory, carnelian, tiger’s eye and garnets. This one was silver and crystal, turquoise and moonstone and bone. She could just see the glowing tip of the Firebird’s feather sewn over one shoulder, exactly in the place Lugh’s lay. Lugh said it dreamed of being a wing.

Nausea rose in her throat, curling up like a bad smell. The cloak twisted on its hook. She was slick with sweat.

She closed her eyes, trying to hang onto her fury and forget she felt like a pile of soiled laundry, shapeless and smelly.

Blessedly, the cart stopped.

She heard Dar’s voice, then Lugh’s, remonstrating. Another voice cut in, confident and firm, laying down the law. She smiled in spite of her misery, keeping her eyes shut. Heks. She was saved.

Heks banged open the back of the cart. “This can’t be comfortable, child,” she said. “Wouldn’t you rather come out into the air?”

Nausea receded with cessation of movement.

“Yes!” said Mary with relief. “I was beginning to get sick.”

Heks gave her a strong hand, hoisted her up from her damp pallet and passed her to Lugh, who stood waiting at the back of the cart to help her clamber out. He looked so worried her irritation evaporated.

“I know you want me to be out of the sun,” she said, “but it’s too hot and closed back here.”

“I’ll look after her,” said Heks. “You enjoy your brother.”

“Brother!” Mary almost shouted. Lugh looked taken aback. “Dar’s my twin brother. I wanted to surprise you.” He smiled, pleased with himself.

Heks took Mary firmly by the arm while she was still deciding between shouting and shrieking. “Come along,” she said.

Mary came. Usually strong willed, any demonstration of determination swept her helplessly along in its wake these days.

They evidently had stopped for a break. Mary saw villagers relaxing on the grass, eating, drinking and talking together. They had entered a forest and the trees cast welcome shade.

Heks led her away from the others to a stream screened behind willows. Mary bared her feet and sat on a log, soaking them blissfully. Heks stood behind her, unraveled her thick hair, tidied it with a comb from her pocket, braided it and pinned it on the back of her head, making Mary feel ten degrees cooler. She pressed a water-soaked rag to the back of Mary’s exposed neck.

“Why are men so stupid?” Mary asked.

Heks snorted with laughter. “They’re only men, that’s why. Poor things.”

Mary laughed too, but felt tears threatening.

“Why didn’t he tell me? I’ve met Dar before and he never said anything.”

“Because he doesn’t know better than to surprise a pregnant woman. You gotta teach him.”

“Teach him! I’ll teach him, the idiot!”

“You are teaching him,” said Heks. “But take it easy on him. He doesn’t know what it’s like,” she gestured at Mary’s curving belly. “And he loves you. He’s worried.”

***

Mary liked Dar. They’d hardly spoken at initiation but now there were slow miles in which to get acquainted.

At first glance, the twins weren’t the least alike, but together they formed a perfect balance. Dar was quick-tongued, impulsive and darkly passionate. Lugh was steady, primitive and blunt. Lugh acted. Dar thought. Watching them together fascinated Mary.

Gradually, she identified their similarities. They both played bone flutes, though she hadn’t heard Lugh play since the Night of Seeds. They each possessed a cloak, obviously made by the same hand. They were both natural leaders.

She admitted to herself she was glad to surrender to their leadership. There was no question about the fact that they were leading, either. Dar had somehow taken charge of part of a small village, though she’d only heard bits and pieces of that story, something about a murdered woman and an argument over conventions. It sounded complicated. At any rate, Heks, Gabriel, a couple called Liza and Brian, and a few others had decided to make a life somewhere else, and a motley assemblage of animals, carts, tools and household goods traveled along behind Dar, in his rather faded cart, like children behind an enigmatic pied piper. Dar was, in fact, following the White Stag, and no one had the slightest idea where he was taking them.

It was odd. Everything was odd, not the least her changing body and its new resident. Odd and exhausting.

She rode for a while with Gabriel, enjoying his gossip about his fellow travelers. Heks had made a pallet for her in the back of Gabriel’s open cart. After a while, she left her seat next to him and climbed into the cart to take a nap.

RAPUNZEL

Juliana’s house at the bend of the river lay many weeks and miles behind. Rapunzel was hardened with walking, lean and brown with sun-filled days.

She still followed the eye’s guidance.

She’d discovered, to her amusement, she’d retained the power to choose to be the ugliest woman in the world or herself. Several times she’d entertained herself with this new toy. It appealed to her sense of mischief to attract and then repel attention.

Harvest season lay ahead, and she began to think of winter. She’d been on the road a long time.

Still, this day was hot and fine and she need make no decisions immediately. She felt content to follow the eye, which appeared to be leading her into a town. When this happened, she took advantage of the chance to spend a night in a bed, or at least under a roof, and restock her supplies. Tonight, she could buy a hot meal.

She was making for a likely-looking inn when she passed a crowd.

“She’s a witch!” shouted a man.

“Go away, witch!” said another amid general muttering.

“Leave her alone, poor soul!” A woman’s voice, shrill but determined.

Rapunzel stopped, trying to see past the clot of people to the source of trouble. She elbowed a fat man’s back and he grunted with pained surprise and turned, glaring. When he saw her face his gaze dropped, angry flush subsiding.

“Please,” she whined, “what’s happening?”

“It’s an old woman, making a nuisance of herself,” he said gruffly. “Scaring people.”

Rapunzel pushed in front of him and made her way through the cluster of bodies, kicking and jabbing. Most people, seeing her face, automatically took a step back. She’d made her way through more than one crowd in this manner. Ugliness discouraged close contact.

At the front, she found a middle-aged woman with disheveled hair and a gaunt face backed up against a fence. Her eyes were wide, white showing all the way around them. She wrung her hands and gabbled in a low voice.

Rapunzel instantly felt infuriated. She turned in front of the woman, shielding her, and faced the crowd.

“Why are you abusing my mother?”

“Your mother?” asked a woman. “See,” she shouted to someone else in the crowd, “she’s not a witch! A witch would do something about a daughter who looked like that!”

Rapunzel allowed an expression of shame to cross her face and dropped her gaze, letting everyone get a good look at her.

“She’s not a witch,” she said, but quietly, so the crowd had to strain to hear. “She gets…confused. She can’t help it. You’re scaring her.” She’d discovered most people assumed she was witless as well as ugly and took pains to sound childish.

“You should keep a closer eye on her,” a man said reprovingly.

“I do my best,” said Rapunzel, allowing her eyes to fill with tears. “I try, but she slips away sometimes.”

With satisfaction, she noted the crowd loosen. Several people turned away. A weeping female simpleton and her deranged mother provided little entertainment. Rapunzel, knowing well how she looked when she wept, slumped her shoulders and held her mouth half open, sobbing and showing crooked, stained teeth. Her nose ran.

Behind her, the so-called witch mumbled and cowered.

After a few minutes they stood alone, though passing people cast sidelong glances of curiosity at them. Rapunzel, mindful of this, artlessly wiped her face and blew her nose on her sleeve, carelessly smearing mucus across her cheek.

“Will you come with me?” she asked the other in low tones. She put out her hand.

Somewhat to her surprise, the woman took it, and allowed Rapunzel to lead her out of town.

A hawthorn hedge bordered fields along the road. Rapunzel watched for a gap and when she found one, they pushed their way through it. Hands still linked, she led the woman to a grassy spot. The hedge shielded them from the road. Rapunzel dropped easily to the ground, and the other woman followed suit.

She’d stopped mumbling and her eyes showed less fear. Rapunzel didn’t know what on earth to do with her.

“I’m Rapunzel,” she said. “What’s your name?”

“You’re for the silver fish in the dark,” she said, “but that’s not your face.”

“It’s not my face,” said Rapunzel carefully, feeling her way. “Will it frighten you if I change into my real face?”

“No,” said the woman, and watched the transformation serenely.

“You’re not my daughter, are you?” she asked.

“No,” said Rapunzel. “I said that so they’d leave you alone.”

“Thank you. I’m Cassandra.”

“Are you alone, Cassandra?”

“No. Golden rope fell down stone wall and caught me.”

She made just enough sense to be eerie, Rapunzel thought. No wonder she’d frightened people!

“Where do you live?”

“Oh, I can’t live somewhere!” Cassandra looked away and began humming to herself. She wound a lock of grey-threaded brown hair around and around her finger.

“What am I going to do with you?” Rapunzel muttered to herself.

“Follow the blue,” said Cassandra, looking across the field. “Follow the blue and silver and gold shall meet and I…and I…” she hesitated, looking bewildered. “But silver and gold already met,” she said confusedly, “didn’t they?”

She looked at Rapunzel appealingly. Her face was strained.

“I don’t know,” said Rapunzel gently.

“Follow the blue,” said Cassandra decidedly. “Follow the blue.”

“Do you mean this?” Rapunzel held out her hand, the open blue-eyed marble in her palm.

Cassandra hardly gave it a glance. “Follow, follow, follow,” she sang to herself. “Gold rope and black robe.”

“Does someone look after you?” Rapunzel asked hopefully. “Can I take you somewhere before I go on?”

“Winged flower face, loom and gold rope.”

Rapunzel gave up. The open eye in her hand looked steadily at Cassandra.

“Let’s walk,” she said with a sigh. “I want to get away from that town.”