The Hanged Man: Part 9: Lughnasadh, Part 10: The Hanged Man (Entire)

PART 9 LUGHNASADH

(LU-nuh-suh) August 1; first harvest festival; midpoint between Lithia and Mabon. Sacrifice, harvest, planning the next cycle of growth.

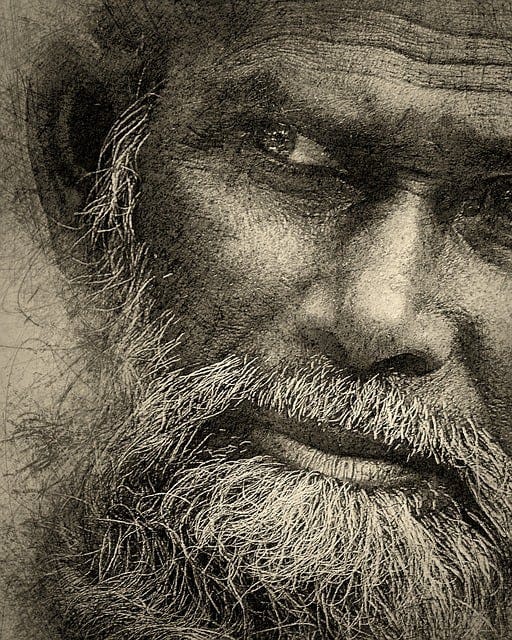

The Emperor

Kingship; healthy male power

ROSE RED

Rose Red sat with her back against her favorite oak tree. A large, clustered ram’s head mushroom grew at the base of the trunk. The tree made her think of Gwelda and her friend, Borobrum. The thought of Gwelda comforted her.

She and Rowan had come…home? That’s what Rowan had said when they found the spring guarded by rowan trees. She wasn’t sure what home meant, or if it meant the same thing to them both.

Rowan Tree (the place name was so obvious they didn’t even discuss it), comprised several hundred acres of mixed forest, river and meadow. As far as Rose Red could tell, it throve and needed nothing from her. She thought Rowan was far more useful than she; at least as a fox he became part of the natural balance.

He was delighted with the place. In his fox shape, he assessed rodent and rabbit population and found the scent of his own kind, as well as beaver, weasel, skunk, wild pig, bear and deer. He dug in rich soil, brushed through thickets, clawed open rotted fallen trees. He found a bee hive and a crow’s nest, occupants fledged and flown but hanging around making sarcastic comments on all that occurred below them. He fit in as naturally as the tree she leaned on.

But what did Artemis expect her to do here?

The rowan trees were fruiting. Rose Red took off a dead or diseased branch here and there, but they flourished without attention. In fact, all the woods did flourish without attention. Artemis had taught her that was the point. Rose Red’s job consisted of simply protecting and allowing the balance already present.

But what was she to do?

She’d been so caught up in her training, the initiation and its aftermath, and Rowan, she’d never thought about what would come after it all. It was ridiculous to have come so far and learned so much, only to find herself suddenly with nowhere to go and nothing to do.

They’d done some work. They mended the three stone walls around the spring. Rose Red wondered who’d built them, and when. The spring bubbled vigorously up from the ground and then dove out of sight again. The walls enclosed a space much larger than the spring, in fact. They talked about roofing the structure and moving the walls in, but in the end decided to respect the original shape of the place.

“There must be some reason the walls were built this way,” Rose Red said. “We’re new here. It doesn’t seem right to start making changes.”

Trees and grass had begun to whisper of fall’s approach. Out in the world, early harvest had begun, but Rose Red felt as though she and Rowan dwelt in a place apart.

She must prepare for winter.

She had an idea about shelter. She’d found a giant old oak at the edge of the wood. Standing under it, she had a fine view of a treeless slope and the river below. It shaded out smaller trees, so the ground remained relatively clear under its canopy. She sat under it every day, leaning against the trunk and being still or climbing into the crown among leaves and acorns.

One day she’d shown it to Rowan. “I want to build a house here, using the tree trunk as part of a wall,” she said. “Do you think it can be done?”

He padded around the trunk, looking at everything, fox like, though he wore his human shape. He stretched out his arms, measuring the oak’s girth.

“I’m certain it can be done,” he said. “It’s a good place. I like to think of you here. But how will you do it?”

Rowan, though he leapt lightly between fox and man shape, had a vulpine nature rather than a human one. He could no more master tools to fell trees, cut them up and build a house than he could fly, even if he wanted to. He didn’t want to. A fox has no need to plan for the next meal or winter shelter.

He’d called out of Rose Red a primitive passion that frightened her. She resented his power to rouse her, to make her feel and want. At the same time, she could never go back to the frozen girl she’d been. Persephone, Baubo and Artemis had been right. The ability to live sensually was power. She longed to explore that power more fully, but remained unwilling to fully explore its lineaments of rage, grief, lust and even joy.

Being with Rowan had also cracked her defensive isolation. As a lover he was immediate, insistent, flesh, fur and scent blotting out everything else, like a storm. As a companion, he was aloof. Sometimes she wouldn’t see him for days, though she knew he remained nearby. He lived in scent, sound and experience of now, fully engaged and self-contained. He had no need to talk.

She envied him his complete freedom from self-consciousness. He didn’t try. He just was.

She felt lonely.

She resented her loneliness most of all. Vasilisa, Jenny, the dwarves, Artemis, Rowan — all had conspired to shatter her self-sufficiency and independence by teaching her what friendship and love were. But had it been self-sufficiency and independence or had it simply been a fearful loneliness all along, only now truly revealed to her?

She sighed. What was the use of these feelings and insights now? She was responsible for a place in the middle of nowhere, the only human being for who knew how many miles.

Winter approached.

How would she manage?

Birds exploded out of the tops of nearby trees. A squirrel burst into a scolding chatter. Down at the river, the family of crows had been snapping up a half-eaten fish left by a weasel. They rose into the air, cawing harshly, and sped into the trees to see what was happening.

A fox streaked out of the long grass on the slope below her as she stood. It melted into the woods, heading toward the disturbance, and she followed, moving swiftly and carefully through the trees, keeping her hand near the knife in its sheath at her belt. Disturbed birds gave alarm calls in the tree tops.

She heard voices from the direction of the spring. The stand of rowan trees stood ahead. She paused among them.

A young woman of about her own age with disheveled dark hair over her shoulders looked around the clearing in disbelief. Behind her stood a man, sturdy and broad of chest, with straight black hair hanging in his eyes. His face wore a look of complete bemusement. He turned and looked over his shoulder at the newly-walled spring. Out of the gurgling shadows another figure appeared, maneuvering some kind of a complicated framework.

Rose Red stepped away from the tree.

“Kunik?” she said.

He turned at the sound of her voice. A broad smile crept across his face as she came toward him and he pushed his hair out of his eyes.

“Rosie!”

He caught her in an enormous hug. He felt warm and solid and smelled of wood smoke and…rain?

“You’re wet!” she said.

“It rained!” he said, as though reporting a miracle. “Maria brought rain to the desert!”

Rose Red disengaged herself.

The dark-haired young woman laughed. “Kunik, she has no idea what you’re talking about. Look around you! We’re not in the desert anymore.” She smiled at Rose Red. “I’m Eurydice. Sorry to drop in on you like this! This is— “

“Maria?” said Rose Red, feeling more and more bewildered. “It’s you, isn’t it?”

“Yes, my dear, it’s me,” answered Maria, running fingers self-consciously through cropped silver-streaked hair.

“Did anyone see what happened to the snake?” asked Eurydice.

***

They went down to the river. All three newcomers were soaked and it felt chilly in the shaded woods. There were fish in the river and everyone was hungry. There was no sign of Rowan. Rose Red wasn’t surprised.

She’d already built a fire ring on a patch of bared earth. Kunik caught several fish out of a pool formed by a beaver dam while Eurydice and Maria dried in the sun. They cooked chunks of fish on skewers over hot coals and shared Rose Red’s stash of fruit and nuts as well as what the others had in their bundles.

By the time the fish was cooked, Rose Red and the others had heard Eurydice’s story of the gateway under Yggdrasil and her journey, guided by the snake, to the Womb of the Desert.

As they ate, Maria and Kunik between them told of their meeting in the desert and subsequent events, Maria giving a brief account of her lost boys for Eurydice.

“…and then Maria cried and her tears strung the loom,” said Kunik. “Nephthys danced and chanted while clouds gathered. We could smell rain in the air. Maria’s tears made a fountain and a well opened and the roots began to drink. Rain fell and leaves uncurled on the trees. Life came back into the bones and then Eurydice was there and Nephthys raised her wings…and then we found ourselves here.” He finished awkwardly. He looked at Maria. “It sounds mad, doesn’t it?”

“It sounds comforting,” said Rose Red.

“What?” he looked amazed.

“Kunik,” she said, between tears and laughter, “Kunik, if you knew what I’ve done — what I’ve seen! I’ve so much to tell you! But first, where are you going?” she included all of them in the question. “What will you do now?”

“We’ve talked about that,” said Maria. “Kunik, and I, I mean.” She smiled at Eurydice. “We’re looking for a home.”

“I don’t know that I’m looking for anything, honestly,” said Eurydice. “I’ve been looking for myself, I think. I do know I’m a doorkeeper. I open the way. That’s what happened under Yggdrasil and at the — what did you call it?” she turned to Kunik.

“The Womb of the Desert,” said Maria.

“Yes. The Womb of the Desert. It’s a portal, you see. We opened it and came through to here.”

“It’s a spring,” said Rose Red.

“It’s a portal, too, said Eurydice. “I saw rowan trees guarding it. A powerful gateway.”

“It needs a keeper,” said Rose Red. Eurydice looked taken aback.

“Now tell us about yourself, Rosie,” said Kunik.

She began with parting from Maria and Mary, leaving out mention of Rowan and Rumpelstiltskin.

“…and I was feeling lonely and wondering how I’d manage alone, especially during winter, and then birds exploded up out of the trees and I went to see what was happening — and there you were,” finished Rose Red.

They looked at one another.

“Are…are you asking us to stay here — with you?” asked Maria.

Before Rose Red could answer, Kunik stood. “Will you show us the land?” he asked.

***

They stood under the oak tree, looking across the grassy slope and river valley.

“We need to do some building,” said Kunik.

“And planting,” said Eurydice.

“I know how to keep chickens,” offered Maria.

“We’re going to need help,” said Kunik. “I don’t know much about building.”

“All the wood we need is here,” said Rose Red. “There’s stone, too. I can help with that part, but I don’t know how to build and we’ve no tools or way to transport heavy material.”

“We need to think about food, too,” said Eurydice. “It’s too late to garden now but we can lay out and plan gardens and animal pens. Kunik can help with that.”

“This winter may be hard,” admitted Rose Red, “but there are still several weeks of good weather. We can harvest nuts and fruit from the land. There’s a market a half a day away. If we can make some shelter and buy or hunt meat, we’ll be fine.”

“Building and food, then,” said Maria. “Are those our priorities?”

Everyone nodded.

“We need someone to help with trees, then, right? Harvesting, cutting up and moving.”

“We must plant a replacement for every tree we take,” said Rose Red, “and plant well, in a good spot where it can thrive…” She trailed away as a thought occurred to her.

She glanced around them at the forest. “Rowan?”

He came out of a thicket in his fox shape, moving with feline grace. She knelt and spoke to him. “I’ve had an idea. Can you find the White Stag? Find him and bring him here. I want to send a message to Artemis.”

“The White Stag!” Maria repeated.

The fox melted away.

“Oh,” said Rose Red, standing again and seeing their amazed faces. “That’s Rowan.” Her face flushed and she avoided everyone’s eyes. “He’s a fox,” she added unnecessarily. “You know the White Stag?” she asked Maria.

“I think so,” said Maria. “I saw it the day we found the Well of Artemis, in fact.”

Eurydice cleared her throat. “My family lived among trees,” she said to Rose Red. “Tell me what your ideas are about a house here. I’d like to do something like that near the spring.”

GINGER

“Happily ever after,” Elizabeth had sneered. “It’s all very well for you! What about the rest of us, locked up here until we’re too old for anyone to want us? We know nothing, we’ve been nowhere and we’ve had no life because of you. Now you go off to live happily ever after and leave us.”

“But I was locked up, too!” Ginger had said. “Mother said I must guard, I must watch over you, I must hold the secret! I promised her!”

“You cared more about a mother who left us than your sisters!” retorted Elizabeth. “All you cared about was controlling us.”

“No. I didn’t want power. I didn’t want control. I hated it!” Ginger began to cry in harsh sobs that hurt her throat. “I had to protect you!”

“Protect us? From what? No one can stop us from dancing! No one cares, anyway. You stole our lives!” Elizabeth slammed out of the room. Sarah, the sister closest to Ginger in age, took Ginger in her arms.

“Hush. She doesn’t remember Mother the way we do. Most of them don’t. Gemma doesn’t remember her at all. They don’t understand.”

“Mother made me promise, Sarah. I had to keep the secret. Father …”

“I know. Mother thought it was the only way, and so did you.”

“All those dead men …”

“We couldn’t help it.”

“They’ll never forgive me.”

“They will. They’re shocked and scared right now, and they’re taking it out on you because you’re the closest thing they have to a mother.”

Ginger sat up, wiping her face with her sleeve.

“I’m shocked and scared too. I know we’re free now, but I can’t truly feel it, you know? I can say the words, but they don’t mean anything. I feel numb. What does ‘happily ever after’ even mean?”

Sarah laughed. “It means Elizabeth reads too many fairy tales, for one thing. I’m numb, too. Maybe we all are. It’s happening so fast, and we’re running in so many different directions, like a mob of disturbed geese, it’s no wonder we feel half crazy.”

“What are you going to do?”

“I’ve no idea. I can’t even get to what I want to do. There was always just what we had to do, and now suddenly there are choices to make and I have no idea how to do it.”

They gazed at one another, at a loss.

“Talk to Radulf,” said Sarah. “He’s a good man, a man of the world. He’s kind and he cares about you. Maybe he can help.”

“Sarah, I don’t want to get married right now.”

“Then don’t. And don’t keep it secret, the way you feel. If we’ve learned anything, it’s how that turns out! Just tell him the truth.”

***

“Radulf, what do you think ‘happily ever after’ means?”

They were riding. Every day they went out together, ranging well beyond the castle walls that had previously bounded Ginger’s life. They roamed over the countryside, exploring, talking, exchanging stories and getting to know one another.

They were easy companions. He was like the brother Ginger had frequently longed for, solid, dependable and, best of all, older. Someone who bore some of the burden instead of becoming part of it. He was a friend. Ginger trusted him more every day.

“That’s odd,” Radulf said. “I’ve been thinking about happily ever after myself lately.”

“Tell me.”

“Well, I told you about Marella, and my family, and my wife.” He glanced at her and she nodded. She knew the full story of Marella’s life and death, as well as the events during the initiation and his subsequent journey back to his old home.

“I realized a few weeks ago what I want now is to find a place to belong. I’m tired of wandering through everyone else’s life. I want to find a life of my own. I don’t know where, or exactly how to find the right place, but that’s what I’m looking for. I heard about you and your family from my friend Dar— “

Ginger nodded again. “The peddler.”

“Right. It intrigued me, as you know, so I came to find out more about that. Maybe I thought I’d find answers here for myself. Maybe I thought the answer to my longing was here, and I’d find it and live happily ever after. You know, be content and peaceful and have exactly what I want, even the things I don’t know I want, and be free of what I don’t want.”

“That sounds like a fairy tale. My sister Elizabeth is addicted to them. She said I was going to live happily ever after. We were fighting at the time.”

“Happily ever after is a satisfying ending to a tale, but what does it mean? In real life, things go on happening. People get sick, and fight, and go on making choices. Things change. I’ve been laughing at myself, because I know by now most of the time I don’t know what I want. I know what I don’t want and I know about some things I think I want, but we can never know all that might be possible, so how can we choose what we want out of an infinite set of possibilities?” Radulf shook his head.

“I’m glad you said that.”

“What?”

“That you don’t always know what you want.”

“Most people don’t. We may think we do, but even when we get exactly what we want we soon begin to want something different. It’s human nature, I think. Reality is always different than dreams.”

She’d longed for a life of her own, a chance to explore the world and herself. Would marriage to this stranger (for he was a stranger, really), be a life of her own? Or would she be limited by responsibility and loyalty before she even started, just as she’d always been?

Every face she saw outside the castle was strange. How would she ever make friends or call any place home that wasn’t her father’s castle and the big bedroom where she and her sisters had spent every night of their lives? And that wasn’t the hardest thing. The hardest thing was also the most difficult to talk about.

What about dance?

Except the word ‘dance’ was so inadequate.

What about spirit and body and passion? What about drumbeat and freedom of nakedness? What about sacred guides? What about other women who knew how to be fierce and wild — or who wanted to learn?

She feared no relationship could substitute for dance, and without this powerful, private center she’d collapse like an abandoned building.

Yet she’d chosen to leave her old life and every day she respected and trusted Radulf more. Was it wrong, this grief and longing for something of her old life? Was it disloyal? Should she be grateful for what she had, and embrace it without looking back? After all, she’d achieved relative freedom, hadn’t she?

There was no one to ask.

***

“This is Fengate,” said Radulf, reining in his horse. “This is the part of the kingdom your father has offered to me.”

“It looks nice,” said Ginger.

“It is nice. I’ve explored a little. It’s a market town, reasonably prosperous, with several businesses. There’s not a thing wrong with it.”

Ginger glanced at his rueful expression.

“So?”

“So, it’s not what I want. I want to want it, but I don’t. When I think about living here, overseeing the town and the land around it, I feel bored.”

He sounded so annoyed with himself that she laughed.

“What about finding your place and making friends?”

“I thought that’s what I wanted, but now I wonder. Here’s a perfectly good opportunity, and I can’t even feel interested. I can’t help feeling when I find what I want I’ll recognize it. I’ll feel something beyond polite interest!” He turned in the saddle slightly, facing her. “What about you?”

She was taken aback. “What about me?”

“Do you want to get married, choose a house in this town, and settle down? Do you want children? Do you want to go back to the castle? I think you’d be freer now.”

“No.” She felt herself flush and dropped her gaze to the horse’s neck.

“No?”

“No.”

Radulf chuckled. “Would you care to elaborate?” he invited.

“I don’t want to sound ungrateful,” she began.

“Ginger,” he interrupted.

“What?”

“Are we friends?”

“Oh, yes!”

“Good. Then tell me what you want. As friends, we don’t owe each other anything. As friends, let’s assume we want what’s best for one another, what’s happiest. You’re not ungrateful. You’re not stupid. You’re a lovely woman and your life has suddenly changed out of recognition. You can make choices for the first time. You’re free. Satisfy my curiosity. What do you want?”

“Oh, Radulf, I don’t want to get married right now!” She met his gaze as bravely as she could. He smiled, to her enormous relief. She straightened her shoulders, feeling unburdened. “I don’t want to go back to the castle. It felt like a prison. My father won’t miss me. He doesn’t need me. My sisters are going in several different directions. I want to go forward, but I don’t know who I am or how to be free. I don’t know what I want. I just know some things I don’t want, like you said.”

“As good a place to start as any,” said Radulf.

His mount shook his head irritably, setting the bridle jingling.

“Let’s ride,” suggested Radulf. They turned the horses and rode away from the town into the summer countryside.

“Ginger, you’re lovely, as I said, but the truth is I don’t want to marry again.” He glanced at her. “I don’t want to hurt your feelings, either, you know.”

“Friends,” she said, smiling.

“Yes. And as your friend, I’m not going to leave you alone in the world until you have your bearings. You’ll need to find a place to live and make at least a couple of new friends. I’ll talk with your father and decline his offer of land to oversee and a wife. If it seems appropriate, I’ll move out of the castle and find someplace to stay nearby, but I won’t leave you until you feel ready to be on your own. I’m in no hurry, and maybe I’ll find some path into my own future here with you.”

“Thank you,” said Ginger with gratitude. “I don’t even know how to begin!”

“Things take time,” said Radulf. “I think we should enjoy the summer and explore. Eventually you’ll see the next step you want to take, and so will I. In the meantime, we each possess a friend and companion to talk to and discover with.”

“Right now, that sounds like ‘happily ever after’ to me,” said Ginger.

He laughed. “Good. Me, too.”

KUNIK

The grassy slope spoke to Kunik. He whittled a quantity of rough stakes and one sunny day everyone assembled on the slope. He grouped them at the bottom, their backs to the river, looking up.

“There, see the fold running along there? It makes a steep bank about five feet high. If we built a long low shed, or several smaller ones right there, we could use the bank as the back wall. That’s south,” he pointed over the river, “so the sun would shine into the shed. We could keep animals there, and make pens out of some kind of fencing, wood or stone or even a hedge if we can plant the right thing.”

“A good, strong chicken house that can’t be dug into,” said Maria.

“Right.” He smiled at her. “Chickens are so vulnerable they need to be completely enclosed. Goats would give us milk and meat.”

“Sheep would give wool,” Maria said.

“Don’t forget pigs!” said Kunik. “Bacon!”

They laughed together.

“The gardens should be near the animals,” said Eurydice. We can use their bedding and waste in the soil.”

“Absolutely,” agreed Kunik. “Now look, see where the fold tapers away into nothing and the slope flattens?” They grouped around him, following his gesturing arm. “We could easily terrace that piece into different garden beds. It’s close enough to take advantage of the animals, it gets good sun and it’ll drain well. Look, see that spot above where the sapling is growing?”

“That’s another oak,” said Rose Red.

“Well, see the thick grass there? It’s a darker green than the rest of the hill. I bet there’s water there, underground, and it’s just above the garden. It would help to make a well for the garden and the animals, wouldn’t it? We can haul water from the river, but this would be easier.”

“So, we’d keep animals and gardens in common?” Rose Red asked.

The others looked at her. “I mean,” she said quickly, “it makes sense, of course, but…I’ve never lived that way before.”

“Look.” Maria pointed up at the top of the slope, near Rose Red’s oak tree. The White Stag stood in sun-dappled shade, looking out across the valley. It seemed to Kunik he wore a crown of oak leaves and acorns, his antlers mingling with the lowest branches of the giant oak. He wondered how long the stag had been there, watching.

***

The White Stag stayed with them for three days, listening to them talk and make plans. He accompanied them when Rose Red took them for a day and taught them the names and habits of fruit and nut trees. There were chestnuts, as well as hazels, acorns and walnuts. She proved a natural teacher, and revealed to them something of the intricate system of balance in the forest.

“We can eat chestnuts, of course, but birds eat them, too, and all kinds of animals. Pigs eat them, so if we do keep pigs and let them run, they’ll help fatten our meat. I’ve only found these few trees in this part of the forest, so I think we shouldn’t use them for wood. They’re too valuable as a food source. We could try to grow more of them, of course. There’s plenty here for us to share, but we must never take more than we need.”

“Now, look at this,” she stopped next to a shrub with sharp thorns and red berries. “This is hawthorn. It makes a great hedge. I thought of it when Kunik showed us how to use the slope. There’s a lot of it in the woods, and it’s another source of food for the birds. It flowers, too. We’ll need to transplant it where we want it and get the hedge going, but after that we’d be set. We can use it as a windbreak, too. I bet snow drifts on the hill in winter.”

“I’m overwhelmed,” said Eurydice. “How are we going to do all this?”

“I think I can get some help,” said Rose Red.

“We found our way here,” said Maria. “Perhaps others will, too. Nephthys told us what we searched for also searched for us.”

The next morning the stag was gone.

***

“How did you find us?” Kunik asked the man called Jan as they stood watching Jan’s giantess wife embracing Rose Red and weeping with joy.

“A fox brought word to Gwelda,” said Jan. “He said Rose Red needed help with some trees and begged us to come lend a hand. I’d not met her, myself, but I’d heard about her from Gwelda. Because of Rose Red, Artemis asked us to help her serve and protect the forest.”

“You’re most welcome,” said Kunik. He’d taken an instant liking to Jan, who was approximately his own size, though not as thick-chested or strong. Under the tousled brown mop of his hair Jan’s face appeared shaped for laughter, every line and fold stamped with humor.

Gwelda bent and carefully returned Rose Red to the ground, wiping her cheeks with the hem of her lime green, tent-like dress and innocently revealing a monolithic expanse of thigh.

Eurydice came into view, toiling up the hill, lifting her thick hair off her neck with one hand so cooler air could reach her skin.

“Eurydice!” Rose Red waved. A crow circled above Gwelda, cawing excitedly. She raised an inviting arm, elbow crooked, and the crow alighted on it, as comfortable as if in a tree. Kunik saw Eurydice’s jaw drop. The crow began to stalk up the arm, still cawing, as though to examine the round face under a thatch of turquoise hair like a bird’s nest.

“Meet Gwelda!” said Rose Red breathlessly, as Eurydice reached them. The giantess bent down and offered Eurydice a thick callused finger while a chipmunk peered out of her sleeve, black eyes bright.

“Eurydice!” called Kunik. “Come and meet Jan. He and his wife came to show us how to harvest wood and build.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said Eurydice, laughing.

After the flurry of reunion and introduction, they followed Rose Red into the edge of the forest. She’d marked several trees for harvest and she showed Jan a clump needing to be thinned. Jan nodded, sized up the tree and gripped his axe.

“Now, I want the tree to fall that way, see? It’ll cause the least damage. Then we’ll trim it in place and leave the trim for the forest to break down and use.” He moved around the tree trunk, using the axe to whittle away at the trunk, judging balance and tipping point. “Gwelda will help drag the tree out into the sun to dry, and when we’ve cleared and thinned this spot, she’ll help you plant replacement trees.”

Eurydice squeezed Kunik’s arm and slipped away, making a large circle so as to be out of range of falling trees. He knew axes made her uncomfortable, a not unreasonable reaction from a tree nymph. He turned his attention back to Jan.

***

With the help of Jan and Gwelda, the people of Rowan Tree collected two neat piles of logs, one of fragrant green wood, oozing sap, and the other of old, dead trees, seasoned and ready for splitting and shaping. Kunik quickly picked up the art of choosing what to use for fuel, what to set aside for furniture and other household use and what to utilize as building material for fence, shed and house. Jan seemed to know how to make everything needful out of wood and recognized in Kunik a fellow craftsman. They became good friends.

One afternoon, as he and Jan worked in a thicket of alder, they heard a shout.

“Hello!”

“Hello!” Kunik replied.

“We heard the axes! Don’t drop a tree on us!”

He laughed. “No danger! Come ahead!

Two women rode out of the forest on horses, one older than the other.

“We’re looking for the community settling here,” said the older one, smiling down at them.

“You’ve found us.” Kunik brushed a lock of hair out of his eyes. “I’ll take you the rest of the way.” To Jan, he said, “Do you want to come or get on with it?”

“I’ll get this one down. If you don’t come back, I’ll come see what’s doing. Gwelda’s somewhere around,” he finished with a slight air of concern. “The horses…”

“I’ll be careful,” Kunik assured him.

“Who’s Gwelda?” asked the younger woman as he led them through the trees. Behind them, the axe resumed its steady ‘thunk.’

“As a matter of fact, she’s a giantess,” he said. “I’m Kunik, by the way.”

“I’m Persephone, and this is my mother, Demeter,” the young woman said.

“You’re welcome,” said Kunik. “We’re rather rough just now, but friends are welcome.”

“We’re friends,” Demeter assured him. “We brought some things you might be able to use.”

He smiled over his shoulder. “That’s kind. How’d you know about us? Oh, there’s Gwelda. Will the horses be all right?”

They’d come out of the trees onto the crest of the hill. Ahead swept the grassy slope. Stakes were neatly planted, decorated with tough lengths of vine marking out squares. Some way below them a figure with turquoise hair and a rumpled lime green dress like a canopy picked up young trees with sharpened ends like huge pencils and thrust them into the ground, building a neat, tight fence. Other figures worked on the hillside, but it was hard to look at anything but the fence builder.

Persephone laughed. “That’s Gwelda?”

“That’s Gwelda,” said Kunik. “She takes some getting used to, but she’s the kindest person you’ve ever met. That was her husband, Jan, with me in the forest.”

“Her husband?”

“They adore one another,” he assured her. “Newlyweds.”

They left the horses to graze under a towering oak tree and made their way down the slope.

“We’re planning animal pens along the fold here, and a garden there,” Kunik explained, gesturing. “Here are two friends of mine, Maria and Eurydice. Dreaming of your chicken coop, Maria?” he teased. “We’ve visitors. Meet Persephone and Demeter.”

“Aren’t you beautiful,” murmured Persephone to the two women, and took them both in her arms as Kunik watched in astonishment.

The emotional greeting attracted attention. Gwelda left her fence building and stood watching. Her face lit at the sound of whistling as her husband strolled down the hill, axe in hand.

Rose Red had been down at the river when she saw the strangers arrive and now she joined the group, face damp from the hot climb.

“Persephone!” she gasped, and ran into her embrace.

Kunik laid a hand on Eurydice’s shoulder. Neither she nor Maria seemed able to speak.

“We’ve come, my Corn Mother and I,” said Persephone, arms still around Rose Red, “to aid in your harvest.”

***

They’d formed a habit of sitting around a fire at night talking. Gwelda and Jan possessed a childlike love of stories and they shared their own with delight, interrupting one another, giggling and boisterous. Gwelda became so animated she jumped to her feet and acted out bits, to general hilarity and exclamations. “Be careful, Gwelda! You almost stepped on me!” “Watch out for the fire!”

Entering into the spirit of the thing, the others had shared small pieces of themselves, keeping their stories amusing and playful.

The appearance of Persephone and Demeter brought an element of seriousness to the picnic-like atmosphere. There was nothing ominous about Persephone but she was, after all, the Queen of the Underworld. Eurydice and Maria, the only two who’d actually been to the Underworld, treated her with respect untinged by anything like fear, which went some way to putting the others at their ease. Rose Red treated her like an old friend. They were all fascinated by Persephone’s life in the Underworld.

Kunik noticed Demeter tended to be quiet by the evening fire, watching and listening. During the days, she worked as hard as any of them, laying out gardens, helping build coop, hutch and animal pen, and making helpful suggestions. She and Rose Red spent happy hours together considering strategies for optimal health for trees, soil, animals, plants and people.

Persephone and Hades kept rabbits, and they’d brought two pairs in a basket so Rowan Tree could breed a colony for meat and fur. Under Persephone’s expert direction, Kunik and Jan built a rabbit hutch. Maria was particularly intrigued and spent hours asking questions about the needs and habits of the appealing creatures.

***

“I sat in this same spot more than three weeks ago and wondered how I’d survive the winter, let alone shape a life,” said Rose Red.

It was early morning; mist swathed the river below. Rose Red and Kunik sat in the long grass looking down the slope at the construction of Rowan Tree. Rabbits were installed in the completed hutch. Their first livestock. With Gwelda’s help, several animal pens were built and fenced, nestling into the shelter of the slope. Kunik could see the roof of the chicken coop, tight and strong, though empty.

They were digging a root cellar near the bottom of the hill. Gwelda did most of the work with a trowel the size of a shovel, but they’d all given the project a few minutes each day. Slabs of wood lay piled in the grass next to it; shelves to be put in once the digging was finished. Jan was making a stout door.

Demeter had been helpful about storing food, and she and Persephone and Rose Red took advantage of the horses to harvest what the land provided for miles around Rowan Tree. When the root cellar was finished, fruit, nuts and honeycomb could be safely stored, along with a variety of dried mushrooms and berries.

Jan and Kunik turned their attention to building shelters and houses. These were as varied in location and style as the community members themselves. Their goal was to assure everyone a good roof for the winter. In the spring, refinements could be made, houses enlarged, more furniture built.

Kunik smiled. “At the very moment you were thinking that, Maria, Eurydice and I were moving toward you.”

“Persephone and Demeter had heard about us and they were planning their trip here, too,” said Rose Red. “That was before I thought to send for Gwelda and Jan. Now here we are. I’d never have believed it.”

“I wonder who else will show up?” mused Kunik, leaning back on his elbows. “Look at the color of that sky! Like an abalone shell.”

CHAPTER 32

HEKS

Heks watched Gabriel.

He was a spry old man in spite of his cane, curious, friendly and occasionally acerbic. Juliana’s death had done him a lot of good. He’d been sinking into dotage, bored, lonely and just a tinge bitter, when Dar and Radulf appeared. Now life was full of interest, even adventure. He had new people to talk to, new ideas to think about, and he once again felt part of something vital.

He talked to everyone, all the time. No one escaped his questions or his bright-eyed observation. He had a disconcerting habit of seeing and speaking bald truths, having no patience for indirection.

Toward Heks he demonstrated a mixture of curiosity and restraint. They were the same age. She knew he’d possessed a family — once. She found his reticence on the subject remarkable, given his general garrulousness. She didn’t probe, having plenty of her own past she preferred to keep private.

She was aware of his interest in her. A lifetime ago she’d been young and reasonably attractive. Well…young at least. As midwife and healer, she’d known many people, many families, and she’d received her share of surreptitious pats and admiring looks and even a kiss or two… Then Joe came along and swept through her life like an ice storm in spring, glittering and brilliant for an hour, but converting bud, blossom and leaf into wet black decay that turned to slime with a touch.

Gabriel’s interest in her was friendly, no more. He led her on to talk and spent hours walking with her or perched in a cart next to her. He generally ate with her and slept near her. She could see the others gradually accepting them as a pair. He was gentle with her, pretending not to see her reflexive cringe or flinch where there was an unexpected noise or motion. She was certain he’d never hurt her physically. He was a good man.

She thought sourly, I’m certainly trying hard to persuade myself!

The truth was, she, sere, wrinkled, thin-haired and withered, wanted passion, or romance, or one of those shameful words describing what can happen between a man and a woman. A young man and woman. Touch that made fine hairs stand up, scent, texture of hair and skin. She wanted to feel her face cupped in hands just a little too hard, a little too insistent, feel her lip caught between teeth, feel her body respond. She wanted to feel a hard knee between her thighs, nudging them inexorably apart…

And then what? she mocked herself. Then scrabble for oil because I’m old and dry?

“No,” said her heart. “Then he reaches for oil and touches you, caresses you, fingers and opens you until your body remembers and believes and responds. And then you know it’s not too late. It can still happen.”

But that was fantasy, secret and pathetic. In the real world, she was an aging, used-up woman. Beauty and passion had never been for her. Friendship and companionship, now those were possible. Those were appropriate desires. Even an old woman could hope for a friend. She knew her hands retained their skill. She hadn’t forgotten how to help open the way for new life to be born. She could reasonably dream of kneeling beside the miracle of mother and emerging child again, of being a surrogate grandmother. It had to be enough.

Yet she wanted more. She could do more. Not now, maybe, not yet, but someday. Her old life was gone in a whirlwind of blood and fire. She recognized nothing as hers except, oddly, the shawl she’d taken away from Juliana’s house. Gabriel himself -- no. Nothing in her hungry heart recognized him. She wanted nothing from him except to call him friend.

She stayed with Dar and the villagers, not because of Gabriel, but because of their guide.

No one knew where they were going. They wanted a new place to build a community. It would soon be first harvest, and they needed to find a place to spend the winter. As far as Heks could tell, Dar meant to follow his nose and trust in luck. In the beginning, she wasn’t sure she wanted to cast her lot with theirs. Easier, she thought, to make her way alone, try to find the white light she was to follow.

Then, the night before they left, an unearthly White Stag had come to them, slipping out of the woods like mist at dusk. Dar greeted it with reverence, and told the villagers the stag would guide them. Dar appeared relieved, even happy. Heks wondered if the creature had acted as guide for him before. It had melted away between the trees, glowing like a pearl in starlight, as they settled to sleep.

In the morning, Heks set out with the group, taking only the shawl with her.

MARY

“Where are we going?” Mary wiped a tendril of hair off her cheek for what felt like the hundredth time. It wasn’t noon yet. Her pregnancy increased her body temperature and she always felt hot. Today she felt ungainly and cranky as well. The nubile maiden bearing seeds and letting them fall in a wild mist of blood, milk, urine and sweat who’d lain with another Seed-Bearer under the fecund May moon was gone. Her seed pouches were empty and packed carefully away in her bundle.

A seed had taken root and grew in the dark red lining of her belly, and the primordial horned piper walked beside her in dusty boots, glowing with strength and vitality.

“We’re going to meet a friend of mine.” He glanced sideways at her, his face mischievous. “He’s leading a group to a new community. There’ll be wagons and you can rest. A midwife is among them and she can keep an eye on you.”

“And what about you?” She felt nettled, hating how much she wanted to rest. She could see something amused him about his ‘friend,’ but refused to give him the satisfaction of asking. It was too hot.

“I want to see you off your feet, help my friend and find something to do. I want to begin harvest!”

As he’d said this regularly for the last month, she made no reply. She knew he spilled over with energy and could hardly wait for long days in field and orchard. He’d be a big help to a new community, and, frankly, she’d be glad to take a break from his restless vitality. Though he now began to pour out the honey and milk of his strength, she must keep something back, carefully hoard her energy. Her own harvest still lay some way ahead.

“You’re hot. Shall we stop and rest?”

His quick concern diminished her grouchiness.

“No. It’s a hot day. I feel sweaty and fat.”

“We should meet up with them this evening. What do you say to a plate of food you didn’t have to cook and a comfortable bed?”

“I say, lead me to it.” She felt she should show an interest, ask about his friend and the others with him, but she couldn’t summon the energy.

He took her sweaty hand comfortingly in his.

She thought it was like walking hand in hand with the sun.

***

Five hours later, Mary seethed with fury. The cart was stifling. She felt every bit as hot in its shade as she had in the sun, and it didn’t admit a breath of air. In one more minute she was going to sit up, crawl to the back and put her feet on the ground again. The cloak she glared at swayed mockingly on its hook as the cart rolled along the dusty track.

She’d seen that cloak before. During initiation, the enigmatic peddler Dar led the men to their fire, his cloak rippling like dark water in firelight. Now, in the stuffy light, she realized the cloak wasn’t black, but a deep purple. Lugh’s cloak was sewn with gold and copper, ivory, carnelian, tiger’s eye and garnets. This one was silver and crystal, turquoise and moonstone and bone. She could just see the glowing tip of the Firebird’s feather sewn over one shoulder, exactly in the place Lugh’s lay. Lugh said it dreamed of being a wing.

Nausea rose in her throat, curling up like a bad smell. The cloak twisted on its hook. She was slick with sweat.

She closed her eyes, trying to hang onto her fury and forget she felt like a pile of soiled laundry, shapeless and smelly.

Blessedly, the cart stopped.

She heard Dar’s voice, then Lugh’s, remonstrating. Another voice cut in, confident and firm, laying down the law. She smiled in spite of her misery, keeping her eyes shut. Heks. She was saved.

Heks banged open the back of the cart. “This can’t be comfortable, child,” she said. “Wouldn’t you rather come out into the air?”

Nausea receded with cessation of movement.

“Yes!” said Mary with relief. “I was beginning to get sick.”

Heks gave her a strong hand, hoisted her up from her damp pallet and passed her to Lugh, who stood waiting at the back of the cart to help her clamber out. He looked so worried her irritation evaporated.

“I know you want me to be out of the sun,” she said, “but it’s too hot and closed back here.”

“I’ll look after her,” said Heks. “You enjoy your brother.”

“Brother!” Mary almost shouted. Lugh looked taken aback. “Dar’s my twin brother. I wanted to surprise you.” He smiled, pleased with himself.

Heks took Mary firmly by the arm while she was still deciding between shouting and shrieking. “Come along,” she said.

Mary came. Usually strong willed, any demonstration of determination swept her helplessly along in its wake these days.

They evidently had stopped for a break. Mary saw villagers relaxing on the grass, eating, drinking and talking together. They had entered a forest and the trees cast welcome shade.

Heks led her away from the others to a stream screened behind willows. Mary bared her feet and sat on a log, soaking them blissfully. Heks stood behind her, unraveled her thick hair, tidied it with a comb from her pocket, braided it and pinned it on the back of her head, making Mary feel ten degrees cooler. She pressed a water-soaked rag to the back of Mary’s exposed neck.

“Why are men so stupid?” Mary asked.

Heks snorted with laughter. “They’re only men, that’s why. Poor things.”

Mary laughed too, but felt tears threatening.

“Why didn’t he tell me? I’ve met Dar before and he never said anything.”

“Because he doesn’t know better than to surprise a pregnant woman. You gotta teach him.”

“Teach him! I’ll teach him, the idiot!”

“You are teaching him,” said Heks. “But take it easy on him. He doesn’t know what it’s like,” she gestured at Mary’s curving belly. “And he loves you. He’s worried.”

***

Mary liked Dar. They’d hardly spoken at initiation but now there were slow miles in which to get acquainted.

At first glance, the twins weren’t the least alike, but together they formed a perfect balance. Dar was quick-tongued, impulsive and darkly passionate. Lugh was steady, primitive and blunt. Lugh acted. Dar thought. Watching them together fascinated Mary.

Gradually, she identified their similarities. They both played bone flutes, though she hadn’t heard Lugh play since the Night of Seeds. They each possessed a cloak, obviously made by the same hand. They were both natural leaders.

She admitted to herself she was glad to surrender to their leadership. There was no question about the fact that they were leading, either. Dar had somehow taken charge of part of a small village, though she’d only heard bits and pieces of that story, something about a murdered woman and an argument over conventions. It sounded complicated. At any rate, Heks, Gabriel, a couple called Liza and Brian, and a few others had decided to make a life somewhere else, and a motley assemblage of animals, carts, tools and household goods traveled along behind Dar, in his rather faded cart, like children behind an enigmatic pied piper. Dar was, in fact, following the White Stag, and no one had the slightest idea where he was taking them.

It was odd. Everything was odd, not the least her changing body and its new resident. Odd and exhausting.

She rode for a while with Gabriel, enjoying his gossip about his fellow travelers. Heks had made a pallet for her in the back of Gabriel’s open cart. After a while, she left her seat next to him and climbed into the cart to take a nap.

RAPUNZEL

Juliana’s house at the bend of the river lay many weeks and miles behind. Rapunzel was hardened with walking, lean and brown with sun-filled days.

She still followed the eye’s guidance.

She’d discovered, to her amusement, she’d retained the power to choose to be the ugliest woman in the world or herself. Several times she’d entertained herself with this new toy. It appealed to her sense of mischief to attract and then repel attention.

Harvest season lay ahead, and she began to think of winter. She’d been on the road a long time.

Still, this day was hot and fine and she need make no decisions immediately. She felt content to follow the eye, which appeared to be leading her into a town. When this happened, she took advantage of the chance to spend a night in a bed, or at least under a roof, and restock her supplies. Tonight, she could buy a hot meal.

She was making for a likely-looking inn when she passed a crowd.

“She’s a witch!” shouted a man.

“Go away, witch!” said another amid general muttering.

“Leave her alone, poor soul!” A woman’s voice, shrill but determined.

Rapunzel stopped, trying to see past the clot of people to the source of trouble. She elbowed a fat man’s back and he grunted with pained surprise and turned, glaring. When he saw her face his gaze dropped, angry flush subsiding.

“Please,” she whined, “what’s happening?”

“It’s an old woman, making a nuisance of herself,” he said gruffly. “Scaring people.”

Rapunzel pushed in front of him and made her way through the cluster of bodies, kicking and jabbing. Most people, seeing her face, automatically took a step back. She’d made her way through more than one crowd in this manner. Ugliness discouraged close contact.

At the front, she found a middle-aged woman with disheveled hair and a gaunt face backed up against a fence. Her eyes were wide, white showing all the way around them. She wrung her hands and gabbled in a low voice.

Rapunzel instantly felt infuriated. She turned in front of the woman, shielding her, and faced the crowd.

“Why are you abusing my mother?”

“Your mother?” asked a woman. “See,” she shouted to someone else in the crowd, “she’s not a witch! A witch would do something about a daughter who looked like that!”

Rapunzel allowed an expression of shame to cross her face and dropped her gaze, letting everyone get a good look at her.

“She’s not a witch,” she said, but quietly, so the crowd had to strain to hear. “She gets…confused. She can’t help it. You’re scaring her.” She’d discovered most people assumed she was witless as well as ugly and took pains to sound childish.

“You should keep a closer eye on her,” a man said reprovingly.

“I do my best,” said Rapunzel, allowing her eyes to fill with tears. “I try, but she slips away sometimes.”

With satisfaction, she noted the crowd loosen. Several people turned away. A weeping female simpleton and her deranged mother provided little entertainment. Rapunzel, knowing well how she looked when she wept, slumped her shoulders and held her mouth half open, sobbing and showing crooked, stained teeth. Her nose ran.

Behind her, the so-called witch mumbled and cowered.

After a few minutes they stood alone, though passing people cast sidelong glances of curiosity at them. Rapunzel, mindful of this, artlessly wiped her face and blew her nose on her sleeve, carelessly smearing mucus across her cheek.

“Will you come with me?” she asked the other in low tones. She put out her hand.

Somewhat to her surprise, the woman took it, and allowed Rapunzel to lead her out of town.

A hawthorn hedge bordered fields along the road. Rapunzel watched for a gap and when she found one, they pushed their way through it. Hands still linked, she led the woman to a grassy spot. The hedge shielded them from the road. Rapunzel dropped easily to the ground, and the other woman followed suit.

She’d stopped mumbling and her eyes showed less fear. Rapunzel didn’t know what on earth to do with her.

“I’m Rapunzel,” she said. “What’s your name?”

“You’re for the silver fish in the dark,” she said, “but that’s not your face.”

“It’s not my face,” said Rapunzel carefully, feeling her way. “Will it frighten you if I change into my real face?”

“No,” said the woman, and watched the transformation serenely.

“You’re not my daughter, are you?” she asked.

“No,” said Rapunzel. “I said that so they’d leave you alone.”

“Thank you. I’m Cassandra.”

“Are you alone, Cassandra?”

“No. Golden rope fell down stone wall and caught me.”

She made just enough sense to be eerie, Rapunzel thought. No wonder she’d frightened people!

“Where do you live?”

“Oh, I can’t live somewhere!” Cassandra looked away and began humming to herself. She wound a lock of grey-threaded brown hair around and around her finger.

“What am I going to do with you?” Rapunzel muttered to herself.

“Follow the blue,” said Cassandra, looking across the field. “Follow the blue and silver and gold shall meet and I…and I…” she hesitated, looking bewildered. “But silver and gold already met,” she said confusedly, “didn’t they?”

She looked at Rapunzel appealingly. Her face was strained.

“I don’t know,” said Rapunzel gently.

“Follow the blue,” said Cassandra decidedly. “Follow the blue.”

“Do you mean this?” Rapunzel held out her hand, the open blue-eyed marble in her palm.

Cassandra hardly gave it a glance. “Follow, follow, follow,” she sang to herself. “Gold rope and black robe.”

“Does someone look after you?” Rapunzel asked hopefully. “Can I take you somewhere before I go on?”

“Winged flower face, loom and gold rope.”

Rapunzel gave up. The open eye in her hand looked steadily at Cassandra.

“Let’s walk,” she said with a sigh. “I want to get away from that town.”

After that, villages and towns became a problem.

Obtaining supplies and shelter from time to time was a necessary evil, but Cassandra, normally (if that word could ever be applied to her) able to function and communicate reasonably well, immediately came undone when there were other people about. Rapunzel couldn’t judge the accuracy of her predictions. Often, she spoke so confusedly she made little sense, but Rapunzel suspected she prophesied the future. Unfortunately, she was so sensitive and empathic her own prophecies upset her at least as deeply as those with whom she shared them. It took little to turn her into gaunt, wide-eyed incoherence.

But she’d never prophesied for a whole community before.

They were in a middle-sized town, large enough, Rapunzel hoped, to remain anonymous as a rather distraught mother and pitifully ugly daughter. Her plan was to quickly resupply, mostly with food, though Cassandra badly needed a new cloak, and leave. The weather held fine and she put off actually spending the night surrounded by people for the sake of Cassandra’s anxiety.

All went well until they reached the city center, a busy place where a forge did brisk business with a great clanging, a row of horses waiting patiently for shoeing, and several stalls sold household goods and food. Rapunzel was waiting in line to buy meat pies when Cassandra, her arm tucked firmly in Rapunzel’s, tensed, looking around uneasily.

“Cassandra, it’s all right,” Rapunzel said soothingly, recognizing the signs.

“Sparks like flowers,” said Cassandra in a clear voice.

A hammer struck an anvil with a hot, clanging sound. They couldn’t quite see sparks from here, though. On the other hand, there were buckets of fresh flowers in the stall next to them.

“They’re beautiful,” Rapunzel said in a quiet voice, hoping Cassandra would lower her own in response.

She didn’t. “Fire,” she said, her hallucinated gaze traveling around the cobblestoned square.

The man in front of Rapunzel turned to look at them. He moved like a cat, Rapunzel thought distractedly, lean and graceful. She let her mouth drop open, turned her shoulder to the man and muttered, “Hush, Mother. There’s no fire.”

“Fire,” said Cassandra, more loudly. “Flowers in the dark.”

Now other people paused to look.

“Don’t stay here,” Cassandra said to a woman with a chicken under her arm. “Go! It’s not safe! It’s all going to burn!”

The woman backed away, looking scared.

Cassandra began to weep in gasps. “Smoke and flame! Smoke and flame and screams!” She pulled away from Rapunzel. “The stars will go out!”

A crowd gathered. Rapunzel seized Cassandra’s arm and began to drag her away, but people pressed in around them. Cassandra moaned and trembled, pitiable and terrified. “Please! Please believe me! Save yourselves!”

“What’s she say?”

“She says there’s a fire.”

“What? There’s no fire here.”

“Poor lady!”

“Is she cursing us with fire?”

“Nah, she’s not cursing — just saying there is one.”

“Is she mad?”

“She sounds mad.”

“Do you think she’s a witch?”

This last low voice propelled Rapunzel into decisive action.

“My mother needs air,” she said firmly, “please let us through. She’s not well.” She began ruthlessly applying her elbow to the wall of people in front of them.

Someone caught Cassandra’s other arm and Rapunzel tensed, ready to fight. The man who’d been standing in front of them said tersely, “Walk. Straight ahead. Let’s get out of this.”

Between them, they steered the weeping, distraught woman straight at the blocking crowd and it parted, almost magically, though Rapunzel heard some ugly muttering, like a big dog growling low in its throat. The man strode forward, making Rapunzel lengthen her own stride to keep up with him. He swept them through the square and onto a street, up the street to a corner, where he turned.

Rapunzel began to feel irritated. “Thank you,” she said breathlessly. “We’re fine now.”

He didn’t reply.

“We’re all right now,” she said more loudly, and then, “We’re not going this way!”

“You are now,” he said. “I’m not leaving you until you’re safe out of town.”

Rapunzel stopped, still holding tight to Cassandra’s arm, so his steady stride faltered.

“Go away,” said Rapunzel fiercely, quite forgetting the usual cringing, slightly simple manner she adopted when ugly. She glared into the man’s grey eyes. He grinned suddenly, which for some reason further infuriated her.

Cassandra, who had gradually quieted as the market fell behind, and was now strung between them like a bone grasped by two competing dogs, crooned, “black and silver, purple and black, devil prince,” looking into the stranger’s amused face.

Rapunzel felt hot, hungry, and irritated. “Devil? You’ve said black and silver and purple but you never said devil before! You can’t mean this man? I’m not going with him — and neither are you!”

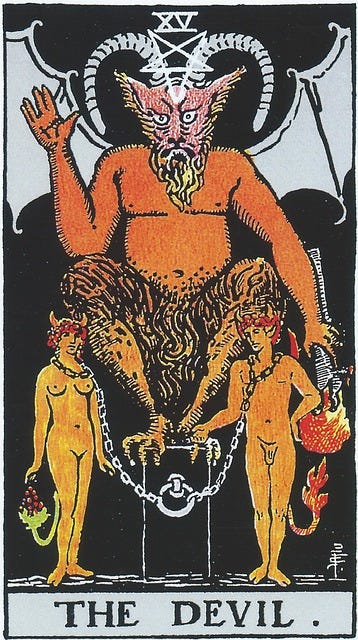

“You’ve heard of me,” he said. “Do you know the old crones say the devil in the Tarot deck symbolizes authentic experience? Perhaps that’s what your mother means. I’m rather fond of what’s real. Truth and the devil are perilously close for some people, I’ll admit.”

“Shut up,” said Rapunzel. “Come on, Cass — Mother! She tugged at Cassandra’s arm, starting to turn away.

“Dar!” A young man and woman approached them, she obviously pregnant and perspiring freely. “Are you all right?” She looked anxious. She carried a heavy-looking basket. Rapunzel smelled the meat pies she’d been going to buy at the stall and her mouth watered.

“All’s well, Mary. I thought it best to get them away quick.”

“We should keep going,” suggested the man beside Mary, also laden with baskets. A thick gold hoop decorated in his left earlobe. “Better to avoid any more trouble.”

Cassandra pulled away from Rapunzel and reached out her hand to the fair man with the baskets.

“Gold and green, milk and honey, silver and gold!” she said, looking from one male face to another.

Rapunzel threw her hands up in the air in mute surrender.

“Well, if you don’t want to come…” the one called Dar said slyly to her.

“Shut up,” she said again, but with less heat.

“You must come,” said Mary firmly. “You can travel with us. We’re quite a big group. You’ll both be safe.”

“I prefer to travel alone,” said Rapunzel stiffly. “We won’t inconvenience you.”

“Oh, la-di-da!” mocked Dar.

“Dar!” said Mary reprovingly. “Don’t tease her!”

He took a step forward and kissed Rapunzel on the mouth.

She, feeling the scene fast slip out of control, changed into her real face and raised her hand to slap his cheek at the same time, so his kiss landed on lips that felt soft and firm rather than slack and spittle-flecked. He jerked his head back and the flat of her hand struck his cheek with a satisfying smack that made her palm sting.

“Do that again,” she said between her teeth, “and I’ll bite your lip off!”

“Silver fish, gold fish, silver fish, gold fish,” said Cassandra, standing in front of Mary with her palms pressed to her bulging belly.

In the end, it was the other man who took charge. He put a heavy basket into Dar’s free hand. Cassandra clung to Dar’s other arm contentedly, and the man with the earring wisely left her alone. Dar’s astonishment quickly turned to speculation and he eyed Rapunzel, opening his mouth to speak, but the other man forestalled him. “Walk,” he said sternly. “Save it for later. Take care of this…lady.” He indicated Cassandra. “I’m Lugh,” he said briefly to Rapunzel.

Dar walked. Rapunzel could almost see the insouciant flourish of an invisible cloak. Silver, black, or purple? she wondered idiotically.

Lugh took the basket from Mary and put it into Rapunzel’s hand. “Interesting trick,” he said, amused. “You don’t need to stay with us but come with us now and eat something, at least. We mean you no harm. Walk!”

She walked, following the imaginary sweep of the devil prince’s cloak.

Behind her, Mary asked, “Lugh, do you think there are two?”

“I don’t know,” he said, “but we were both the Seed Bearers — once.”

“Once,” echoed Mary, rather wistfully.

***

It was a larger group than Rapunzel expected. As she looked around, counting heads, she realized it wasn’t the number of people but the wagons, carts and other conveyances that made it appear so large. They looked as though they were moving house.

Which, she soon understood, was exactly what they were doing.

Lugh sent Dar off with the baskets to distribute their heavy contents, but he kept out food for Rapunzel and Cassandra. To Rapunzel’s irritation, Cassandra refused to be parted from Dar, though he was obviously disconcerted by her attentions. For days Rapunzel had been longing for a break from watching over the odd woman, but now she was surprised to find how much she resented Cassandra’s quick trust of a stranger. Especially that particular stranger! She didn’t protest, however, as they turned away together.

Lugh settled Mary tenderly on a convenient fallen tree in shade and Rapunzel stayed with her, preferring the position of spectator rather than participant.

Mary addressed herself to her food single mindedly, and Rapunzel, eating her own meal with appreciation, took the opportunity to look over the group.

Dar stowed things in a cart, on which once bright paint had faded. There were words on the side of the cart but she couldn’t read them from where they sat. He raised and lowered flaps with ease, and she assumed the cart belonged to him. He unpacked food onto a shelf and others in the group came and helped themselves. She counted eleven people, including Mary.

A woman approached them. Scanty grey hair was twisted up off her neck. Her face was deeply lined. She might have been anywhere from fifty to eighty years old.

“Are you well, my dear?”

Mary nodded, swallowed a mouthful, and said, “Yes. It was hot, though. We encountered a bit of trouble in the market — did you hear?”

“I heard a bit from Lugh.”

“Heks, that woman…”

“Her name’s Cassandra,” Rapunzel put in. “And I’m Rapunzel.”

“I’m Mary and this is Heks,” said Mary perfunctorily. As though hearing her own abruptness, she turned impulsively to Rapunzel. “I’m sorry. I’m being selfish. It’s just that she — Cassandra — made it sound like maybe there are two…” she rested a hand on her belly.

“Did she?” asked Heks, without much surprise.

“You think so too! Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because I’m not sure and I didn’t want to worry you. After all, it makes no difference. Either way, you’re pregnant.”

Rapunzel giggled. “Being pregnant with twins does somehow seem like being more pregnant,” she said apologetically when they looked at her.

“Oh, Heks! How am I going to manage two babies?” Mary wailed.

“Quite well, I should think,” said Heks firmly. “You’ll have help, of course, exactly the kind of help you most need. Anyway, that’s still months away. No need to worry about it today.”

“Where are you going?” asked Rapunzel, curious.

“We’re following a…guide,” answered Mary. Her eyes slid away from Rapunzel’s.

“Where are you going?” Heks asked Rapunzel, “you and your mother?”

“I’m following the ey…a guide, too,” said Rapunzel.

The three of them looked at one another and began to laugh.

“Oh my,” said Mary, wiping her face and then her mouth on her sleeve. “I’ve no room to laugh like that. In fact…” She stood and retired discreetly behind a bush.

When she returned, Rapunzel said, “She’s not my mother. I found her alone in the middle of a crowd. They were talking about witches. She was terrified, making no sense, and apparently alone and homeless. I couldn’t leave her.”

“Of course not,” said Mary, looking appalled. “Poor woman.”

“Is she a witch?” asked Heks with interest.

“I’ve no idea what that word means,” said Rapunzel, somewhat irritably. “She’s a seer of some kind. She knows things. But at least half the time she makes no sense at all, so it’s hard to tell what she’s talking about. Back there,” she gestured in the direction of the town, “she said the market square would burn. She begged people to leave.”

“Oh, my,” said Heks inadequately.

“When I hear the word ‘witch’ I think of the Mother of Witches, Baba Yaga,” said Mary, who hadn’t been following the conversation.

Rapunzel saw her own surprise reflected on Heks’ face.

“You know Baba Yaga?” she asked Mary incredulously.

The vulnerable young pregnant woman suddenly appeared older, more assured. She straightened her shoulders. “No, I wouldn’t say I know her. But she’s been a teacher.”

“You never told me,” breathed Heks.

“Baba Yaga doesn’t appear in casual conversation,” said Mary dryly.

“You, too?” Rapunzel asked Heks.

“Yes,” Heks said tersely.

“Me, too,” said Rapunzel. “How interesting.”

“Your face changed,” said Mary shyly “when Dar kissed you. Are you a witch, then?”

“Dar kissed her?” Heks said in astonishment. “Dar?”

With an air of one laying her cards on the table, Rapunzel groped in her tunic and laid her hand flat, uncurling her fingers, revealing a small white sphere with an open blue eye.

“My guide,” she said resignedly. She turned to Mary, who looked down at the eye in astonishment. “Yes, I can change my face. A gift from Baba Yaga, in fact. And yes, I suppose I am a witch. I was raised by one and she taught me everything she knew.”

Heks reached down the neck of her shirt, between her breasts. She turned over her closed hand and opened her fingers. There in her palm lay two black marbles, slightly larger than Alexander’s eye, studded with points of light.

“Galaxies,” she said. “But the truth is they’re eyes. Baba Yaga…” She trailed to a stop, as though not knowing how to begin an explanation.

“Ah,” said Rapunzel with understanding, and Heks relaxed.

Mary laid a hand on Rapunzel’s wrist. “Please stay with us,” she said.

“I think we will,” said Rapunzel, and relief blossomed within her, catching her by surprise.

MARIA

Gwelda carried stones for Maria’s house.

After much thought, Maria had been surprised to find she wanted to live near the river. Somehow, living water had become a friend rather than a place of horror. On the other hand, she knew the laziest, most sluggish-looking river could rise over its banks and cause chaos. She’d found a slab of half-buried stone thirty feet above the river, right at the edge of the grassy slope. From that spot, she could look across the hill to where gardens and animal pens took shape. The edge of the forest ran along behind her, and between her and the water grew a thicket of alders and other brush.

She’d shown the spot to Kunik, who approved her choice enthusiastically and expanded her tentative ideas. Today they had begun to build.

Working with stone was challenging to the point of irritation, but when the right fit was found, marvelously satisfying. Jan, who seemed to know something about any kind of building, demonstrated with hammer and chisel how to shape stone. Kunik, with his remarkable vision of shape within shape, worked closely with him. The others fetched and carried, making a pile of stones for a chimney. Gwelda roamed up and down the riverbank, bringing back likely looking large stones they couldn’t possibly have moved by themselves.

Demeter and Persephone carried food into the newly-finished root cellar.

They were engrossed in their work and the first any knew of approaching company was a “Halloo!” from the top of the hill.

Maria and the others downed tools and began walking up the grassy swathe. Gwelda, always nervous about scaring people, dropped behind Maria with Jan. Kunik, Rose Red and Eurydice, young and strong, surged ahead. As they climbed, carts came into view, along with horses and what looked like a crowd of people, several of whom came down the slope to meet them, a lean, dark-haired man among them.

“Dar!” said Kunik disbelievingly. “Look, Rosie, it’s Dar!”

Maria watched as they met in a breathless three-way hug. The man called Dar pulled away, smiling. “I’ve brought another old friend,” he said. Maria followed the direction of his gesture. A woman with an unmistakably pregnant profile gingerly stretched her back, a handsome fair man at her elbow.

Maria took a few hesitant steps, searching the woman’s face.

“Mary?” asked Rose Red, at her elbow.

“Rosie! Maria!”

Mary hugged Maria, then Rose Red, then fell into Eurydice’s arms.

Maria, standing back and smiling, realized there weren’t so many people as she’d first thought, perhaps a dozen or so. She saw a young couple, an old couple and what looked like a mother and daughter. Her eyes were caught and held by a head of short golden hair.

“Rapunzel! Rapunzel!”

Rapunzel looked, eyes widening in recognition. She left her haggard-looking companion and met Maria. They hugged enormously.

“I can’t believe it!” Rapunzel said. “You cut your hair! You look wonderful!”

***

Evening found them grouped around the biggest fire they’d had yet. Maria looked around at the scene, feeling satisfied and proud of what they’d created. The horses grazed peacefully in a friendly clump, including Persephone and Demeter’s mounts. Carts parked here and there, blankets and sleeping rolls ready for the night.

A happy feeling of community and reunion embraced the group. Dar told a story with words and flute. Heks was a dark, neat shape beside Mary. Lugh sat in front of them, cross-legged, his cloak furled like jeweled wings around him and his earring catching the light. Rapunzel’s cropped gilt head was next to Cassandra, who looked up at Dar as he talked and played, gesticulating and pacing near the fire, bone flute and cloak glimmering.

An owl screeched, close behind Maria. It made her twitch with surprise. Dar stopped in midsentence and Lugh rose to his feet in a single motion of supple strength, head tilted alertly. He swung around, facing Maria, his back to the fire.

A pale shape, silent as a star, flew to his shoulder. In the moment of landing Lugh appeared to grow taller, his shoulders broader, the carriage of his head prouder. Maria never forgot the picture he made, a god of seed and harvest, the barbarically decorated cloak enhancing and underlining his maleness, with the white owl, blazing eyed, like a sculpture of snow on his shoulder.

Then the owl took off, silent as a blown dandelion seed.

“Good evening.”

A woman stepped out of the shadows, short-haired, lean, looking over a pair of silver-rimmed glasses.

Cassandra, with a wordless exclamation, threw herself into the stranger’s arms.

CHAPTER 33

“It’s like being taken over by a depressingly efficient maiden aunt,” Dar complained. She’s asking everyone, ‘What do you need to be self-sustaining?’ She expects good answers, too. I’m terrified of her!”

“I’m exhausted,” groaned Lugh, stretching out.

“Oh, stop bellyaching, you two,” said Mary. She sat in a chair in the shade, Lugh and Dar stretched out in the grass at her feet. Maria sat with her back against a sun-warmed boulder. “You could hardly wait to get to work, remember?” She stretched out a foot and poked Lugh in the side with her toe. He reached up and grabbed her by the ankle, swinging her foot gently.

“I couldn’t wait to harvest,” he said, but he smiled.

“This is a kind of harvest,” said Maria. “All of us with our stories, finding ourselves here at the same time and working together. It’s like a harvest of personal resource instead of land resource, is all.”

“Well, whatever,” said Lugh, releasing Mary’s ankle and sitting up. He smoothed back his hair. “Is there grass on me?” he asked Mary.

“Fop,” said Dar, with some affection.

“Sloven,” replied Lugh, grinning.

In less than two days Minerva had spent several hours with Maria, whom she appeared to take for granted was the de facto leader of the group, sized up the situation, people and immediate needs. Her energy and intelligence were formidable. Under her supervision, food and shelter for both people and animals were finalized and Maria, grateful, realized they wouldn’t have been ready for winter without her. She was determined to learn everything she could about both business and leadership from Minerva.

Maria made a master list of skills and goods. Lugh set to work directing construction of a slaughtering shed, and Dar added every day to a list of needs, including hooks, hoists, buckets and a variety of saws and knives.

The community at Rowan Tree would slaughter none of their precious stock this fall, but breed and develop small herds and flocks for the following year. Maria knew how to harvest chickens, as did some of the villagers. Persephone promised to visit the following summer and show them how to harvest rabbits. This year Rowan Tree would survive on what the hunters brought in.

Some of the villagers hunted, or wanted to learn the skill, including two women. Rapunzel was also interested. Artemis, who appeared the day after the villagers, proved to be a patient, exacting teacher, and several people developed an interest in archery. Lugh was an expert butcher and over the weeks he taught a small group how to handle meat safely and efficiently, including drying and preserving in salt. Kunik was an expert in the value of fat, traditionally the life-giving fuel of his own culture.

Rosie, with the help of Rowan, oversaw balance, judging the number of grouse, turkey and dove to cull to keep local wild populations healthy and strong, as well as deer and wild pig. They used every butchered animal in its entirety, the bones eventually going to Kunik for carving or shaping. One of the villagers knew how to tan hides, and he quickly chose a couple of apprentices.

Jan and Gwelda headed a team of builders. Kunik was in demand to help choose building sites, and Rowan Tree began to sort itself into households. The stock was housed and cared for in common, and everyone possessed at least one skill to teach to others.

In the midst of this activity, Maria decided to lead the way in revealing her full story to the group. She’d told parts of it before, but left out other parts, depending on the listener. Ever since Persephone and Demeter appeared, she’d mulled over Persephone’s statement about helping with harvest. The association between the Corn Mother and harvest was directly simple. The association between the Queen of the Underworld and harvest was obscure and tinged with unease, especially for some of the younger folk.

Now she thought she could help to foster an understanding of the life-death death-life cycle internally as well as externally. She knew each one of them kept parts of their own stories close, parts that were too tender, risky, or shameful to share. Maria knew how fearful secrets sapped power.

After a day of sun, work, learning, advice, and laughter, she sat cross-legged in the circle around the fire and wove words the way she wove rugs on the loom, color and texture, scent, and touch. In the telling she grew confident; unafraid of judgment. Her listeners were rapt, softened, moved from tears to outrage and horror and back to tears.

When she had finished, Persephone gave a long sigh. “Maria, Maria, I’m so glad. What a beautiful life to live. What a beautiful harvest you’ve made from shame and despair.”

“Not only me,” said Maria. “I’m just the first to speak. Having you here gave me courage. You were the first to teach me how to create life from death and death from life.”

“Our stories intersect,” said Kunik. “Radulf’s a friend of mine.”

“Not to mention Baba Yaga and Nephthys,” put in Rose Red. She shuddered. “I’m glad I didn’t see that version of the Baba. She was horrifying enough in human shape.”

“Maria,” said Demeter quietly, “do you carry the eyes?”

Maria reached into the neck of her tunic, fumbled between her breasts, and held out her palm. Four white marbles lay on it, open eyes dark in firelight.

“Yes,” said Demeter, her voice thick. “I see.”

***

“Maria?”

Maria woke, opened her eyes, and discovered early morning light. Someone was whispering her name.

“Yes? Who is it?”

“Eurydice. I’m sorry to wake you, but something came through the Rowan Gate at dawn. I thought you should know.”