The Hanged Man: Part 9: Lughnasadh

Post #89: In which meetings and reunions ...

(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of The Hanged Man. For the next serial post, go here. If you prefer to read Part 9 in its entirety, go here.)

After that, villages and towns became a problem.

Obtaining supplies and shelter from time to time was a necessary evil, but Cassandra, normally (if that word could ever be applied to her) able to function and communicate reasonably well, immediately came undone when there were other people about. Rapunzel couldn’t judge the accuracy of her predictions. Often, she spoke so confusedly she made little sense, but Rapunzel suspected she prophesied the future. Unfortunately, she was so sensitive and empathic her own prophecies upset her at least as deeply as those with whom she shared them. It took little to turn her into gaunt, wide-eyed incoherence.

But she’d never prophesied for a whole community before.

They were in a middle-sized town, large enough, Rapunzel hoped, to remain anonymous as a rather distraught mother and pitifully ugly daughter. Her plan was to quickly resupply, mostly with food, though Cassandra badly needed a new cloak, and leave. The weather held fine and she put off actually spending the night surrounded by people for the sake of Cassandra’s anxiety.

All went well until they reached the city center, a busy place where a forge did brisk business with a great clanging, a row of horses waiting patiently for shoeing, and several stalls sold household goods and food. Rapunzel was waiting in line to buy meat pies when Cassandra, her arm tucked firmly in Rapunzel’s, tensed, looking around uneasily.

“Cassandra, it’s all right,” Rapunzel said soothingly, recognizing the signs.

“Sparks like flowers,” said Cassandra in a clear voice.

A hammer struck an anvil with a hot, clanging sound. They couldn’t quite see sparks from here, though. On the other hand, there were buckets of fresh flowers in the stall next to them.

“They’re beautiful,” Rapunzel said in a quiet voice, hoping Cassandra would lower her own in response.

She didn’t. “Fire,” she said, her hallucinated gaze traveling around the cobblestoned square.

The man in front of Rapunzel turned to look at them. He moved like a cat, Rapunzel thought distractedly, lean and graceful. She let her mouth drop open, turned her shoulder to the man and muttered, “Hush, Mother. There’s no fire.”

“Fire,” said Cassandra, more loudly. “Flowers in the dark.”

Now other people paused to look.

“Don’t stay here,” Cassandra said to a woman with a chicken under her arm. “Go! It’s not safe! It’s all going to burn!”

The woman backed away, looking scared.

Cassandra began to weep in gasps. “Smoke and flame! Smoke and flame and screams!” She pulled away from Rapunzel. “The stars will go out!”

A crowd gathered. Rapunzel seized Cassandra’s arm and began to drag her away, but people pressed in around them. Cassandra moaned and trembled, pitiable and terrified. “Please! Please believe me! Save yourselves!”

“What’s she say?”

“She says there’s a fire.”

“What? There’s no fire here.”

“Poor lady!”

“Is she cursing us with fire?”

“Nah, she’s not cursing — just saying there is one.”

“Is she mad?”

“She sounds mad.”

“Do you think she’s a witch?”

This last low voice propelled Rapunzel into decisive action.

“My mother needs air,” she said firmly, “please let us through. She’s not well.” She began ruthlessly applying her elbow to the wall of people in front of them.

Someone caught Cassandra’s other arm and Rapunzel tensed, ready to fight. The man who’d been standing in front of them said tersely, “Walk. Straight ahead. Let’s get out of this.”

Between them, they steered the weeping, distraught woman straight at the blocking crowd and it parted, almost magically, though Rapunzel heard some ugly muttering, like a big dog growling low in its throat. The man strode forward, making Rapunzel lengthen her own stride to keep up with him. He swept them through the square and onto a street, up the street to a corner, where he turned.

Rapunzel began to feel irritated. “Thank you,” she said breathlessly. “We’re fine now.”

He didn’t reply.

“We’re all right now,” she said more loudly, and then, “We’re not going this way!”

“You are now,” he said. “I’m not leaving you until you’re safe out of town.”

Rapunzel stopped, still holding tight to Cassandra’s arm, so his steady stride faltered.

“Go away,” said Rapunzel fiercely, quite forgetting the usual cringing, slightly simple manner she adopted when ugly. She glared into the man’s grey eyes. He grinned suddenly, which for some reason further infuriated her.

Cassandra, who had gradually quieted as the market fell behind, and was now strung between them like a bone grasped by two competing dogs, crooned, “black and silver, purple and black, devil prince,” looking into the stranger’s amused face.

Rapunzel felt hot, hungry, and irritated. “Devil? You’ve said black and silver and purple but you never said devil before! You can’t mean this man? I’m not going with him — and neither are you!”

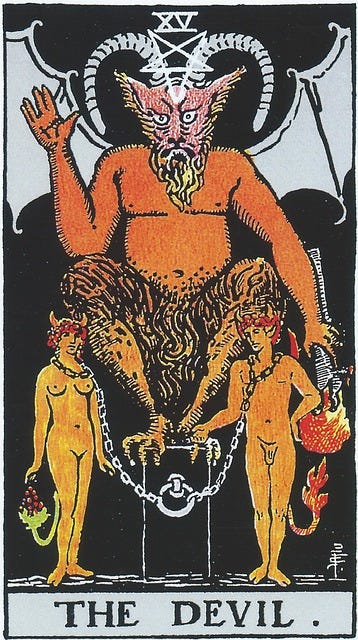

“You’ve heard of me,” he said. “Do you know the old crones say the devil in the Tarot deck symbolizes authentic experience? Perhaps that’s what your mother means. I’m rather fond of what’s real. Truth and the devil are perilously close for some people, I’ll admit.”

“Shut up,” said Rapunzel. “Come on, Cass — Mother! She tugged at Cassandra’s arm, starting to turn away.

“Dar!” A young man and woman approached them, she obviously pregnant and perspiring freely. “Are you all right?” She looked anxious. She carried a heavy-looking basket. Rapunzel smelled the meat pies she’d been going to buy at the stall and her mouth watered.

“All’s well, Mary. I thought it best to get them away quick.”

“We should keep going,” suggested the man beside Mary, also laden with baskets. A thick gold hoop decorated in his left earlobe. “Better to avoid any more trouble.”

Cassandra pulled away from Rapunzel and reached out her hand to the fair man with the baskets.

“Gold and green, milk and honey, silver and gold!” she said, looking from one male face to another.

Rapunzel threw her hands up in the air in mute surrender.

“Well, if you don’t want to come…” the one called Dar said slyly to her.

“Shut up,” she said again, but with less heat.

“You must come,” said Mary firmly. “You can travel with us. We’re quite a big group. You’ll both be safe.”

“I prefer to travel alone,” said Rapunzel stiffly. “We won’t inconvenience you.”

“Oh, la-di-da!” mocked Dar.

“Dar!” said Mary reprovingly. “Don’t tease her!”

He took a step forward and kissed Rapunzel on the mouth.

She, feeling the scene fast slip out of control, changed into her real face and raised her hand to slap his cheek at the same time, so his kiss landed on lips that felt soft and firm rather than slack and spittle-flecked. He jerked his head back and the flat of her hand struck his cheek with a satisfying smack that made her palm sting.

“Do that again,” she said between her teeth, “and I’ll bite your lip off!”

“Silver fish, gold fish, silver fish, gold fish,” said Cassandra, standing in front of Mary with her palms pressed to her bulging belly.

In the end, it was the other man who took charge. He put a heavy basket into Dar’s free hand. Cassandra clung to Dar’s other arm contentedly, and the man with the earring wisely left her alone. Dar’s astonishment quickly turned to speculation and he eyed Rapunzel, opening his mouth to speak, but the other man forestalled him. “Walk,” he said sternly. “Save it for later. Take care of this…lady.” He indicated Cassandra. “I’m Lugh,” he said briefly to Rapunzel.

Dar walked. Rapunzel could almost see the insouciant flourish of an invisible cloak. Silver, black, or purple? she wondered idiotically.

Lugh took the basket from Mary and put it into Rapunzel’s hand. “Interesting trick,” he said, amused. “You don’t need to stay with us but come with us now and eat something, at least. We mean you no harm. Walk!”

She walked, following the imaginary sweep of the devil prince’s cloak.

Behind her, Mary asked, “Lugh, do you think there are two?”

“I don’t know,” he said, “but we were both the Seed Bearers — once.”

“Once,” echoed Mary, rather wistfully.

***

It was a larger group than Rapunzel expected. As she looked around, counting heads, she realized it wasn’t the number of people but the wagons, carts and other conveyances that made it appear so large. They looked as though they were moving house.

Which, she soon understood, was exactly what they were doing.

Lugh sent Dar off with the baskets to distribute their heavy contents, but he kept out food for Rapunzel and Cassandra. To Rapunzel’s irritation, Cassandra refused to be parted from Dar, though he was obviously disconcerted by her attentions. For days Rapunzel had been longing for a break from watching over the odd woman, but now she was surprised to find how much she resented Cassandra’s quick trust of a stranger. Especially that particular stranger! She didn’t protest, however, as they turned away together.

Lugh settled Mary tenderly on a convenient fallen tree in shade and Rapunzel stayed with her, preferring the position of spectator rather than participant.

Mary addressed herself to her food single mindedly, and Rapunzel, eating her own meal with appreciation, took the opportunity to look over the group.

Dar stowed things in a cart, on which once bright paint had faded. There were words on the side of the cart but she couldn’t read them from where they sat. He raised and lowered flaps with ease, and she assumed the cart belonged to him. He unpacked food onto a shelf and others in the group came and helped themselves. She counted eleven people, including Mary.

A woman approached them. Scanty grey hair was twisted up off her neck. Her face was deeply lined. She might have been anywhere from fifty to eighty years old.

“Are you well, my dear?”

Mary nodded, swallowed a mouthful, and said, “Yes. It was hot, though. We encountered a bit of trouble in the market — did you hear?”

“I heard a bit from Lugh.”

“Heks, that woman…”

“Her name’s Cassandra,” Rapunzel put in. “And I’m Rapunzel.”

“I’m Mary and this is Heks,” said Mary perfunctorily. As though hearing her own abruptness, she turned impulsively to Rapunzel. “I’m sorry. I’m being selfish. It’s just that she — Cassandra — made it sound like maybe there are two…” she rested a hand on her belly.

“Did she?” asked Heks, without much surprise.

“You think so too! Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because I’m not sure and I didn’t want to worry you. After all, it makes no difference. Either way, you’re pregnant.”

Rapunzel giggled. “Being pregnant with twins does somehow seem like being more pregnant,” she said apologetically when they looked at her.

“Oh, Heks! How am I going to manage two babies?” Mary wailed.

“Quite well, I should think,” said Heks firmly. “You’ll have help, of course, exactly the kind of help you most need. Anyway, that’s still months away. No need to worry about it today.”

“Where are you going?” asked Rapunzel, curious.

“We’re following a…guide,” answered Mary. Her eyes slid away from Rapunzel’s.

“Where are you going?” Heks asked Rapunzel, “you and your mother?”

“I’m following the ey…a guide, too,” said Rapunzel.

The three of them looked at one another and began to laugh.

“Oh my,” said Mary, wiping her face and then her mouth on her sleeve. “I’ve no room to laugh like that. In fact…” She stood and retired discreetly behind a bush.

When she returned, Rapunzel said, “She’s not my mother. I found her alone in the middle of a crowd. They were talking about witches. She was terrified, making no sense, and apparently alone and homeless. I couldn’t leave her.”

“Of course not,” said Mary, looking appalled. “Poor woman.”

“Is she a witch?” asked Heks with interest.

“I’ve no idea what that word means,” said Rapunzel, somewhat irritably. “She’s a seer of some kind. She knows things. But at least half the time she makes no sense at all, so it’s hard to tell what she’s talking about. Back there,” she gestured in the direction of the town, “she said the market square would burn. She begged people to leave.”

“Oh, my,” said Heks inadequately.

“When I hear the word ‘witch’ I think of the Mother of Witches, Baba Yaga,” said Mary, who hadn’t been following the conversation.

Rapunzel saw her own surprise reflected on Heks’ face.

“You know Baba Yaga?” she asked Mary incredulously.

The vulnerable young pregnant woman suddenly appeared older, more assured. She straightened her shoulders. “No, I wouldn’t say I know her. But she’s been a teacher.”

“You never told me,” breathed Heks.

“Baba Yaga doesn’t appear in casual conversation,” said Mary dryly.

“You, too?” Rapunzel asked Heks.

“Yes,” Heks said tersely.

“Me, too,” said Rapunzel. “How interesting.”

“Your face changed,” said Mary shyly “when Dar kissed you. Are you a witch, then?”

“Dar kissed her?” Heks said in astonishment. “Dar?”

With an air of one laying her cards on the table, Rapunzel groped in her tunic and laid her hand flat, uncurling her fingers, revealing a small white sphere with an open blue eye.

“My guide,” she said resignedly. She turned to Mary, who looked down at the eye in astonishment. “Yes, I can change my face. A gift from Baba Yaga, in fact. And yes, I suppose I am a witch. I was raised by one and she taught me everything she knew.”

Heks reached down the neck of her shirt, between her breasts. She turned over her closed hand and opened her fingers. There in her palm lay two black marbles, slightly larger than Alexander’s eye, studded with points of light.

“Galaxies,” she said. “But the truth is they’re eyes. Baba Yaga…” She trailed to a stop, as though not knowing how to begin an explanation.

“Ah,” said Rapunzel with understanding, and Heks relaxed.

Mary laid a hand on Rapunzel’s wrist. “Please stay with us,” she said.

“I think we will,” said Rapunzel, and relief blossomed within her, catching her by surprise.

MARIA

Gwelda carried stones for Maria’s house.

After much thought, Maria had been surprised to find she wanted to live near the river. Somehow, living water had become a friend rather than a place of horror. On the other hand, she knew the laziest, most sluggish-looking river could rise over its banks and cause chaos. She’d found a slab of half-buried stone thirty feet above the river, right at the edge of the grassy slope. From that spot, she could look across the hill to where gardens and animal pens took shape. The edge of the forest ran along behind her, and between her and the water grew a thicket of alders and other brush.

She’d shown the spot to Kunik, who approved her choice enthusiastically and expanded her tentative ideas. Today they had begun to build.

Working with stone was challenging to the point of irritation, but when the right fit was found, marvelously satisfying. Jan, who seemed to know something about any kind of building, demonstrated with hammer and chisel how to shape stone. Kunik, with his remarkable vision of shape within shape, worked closely with him. The others fetched and carried, making a pile of stones for a chimney. Gwelda roamed up and down the riverbank, bringing back likely looking large stones they couldn’t possibly have moved by themselves.

Demeter and Persephone carried food into the newly-finished root cellar.

They were engrossed in their work and the first any knew of approaching company was a “Halloo!” from the top of the hill.

Maria and the others downed tools and began walking up the grassy swathe. Gwelda, always nervous about scaring people, dropped behind Maria with Jan. Kunik, Rose Red and Eurydice, young and strong, surged ahead. As they climbed, carts came into view, along with horses and what looked like a crowd of people, several of whom came down the slope to meet them, a lean, dark-haired man among them.

“Dar!” said Kunik disbelievingly. “Look, Rosie, it’s Dar!”

Maria watched as they met in a breathless three-way hug. The man called Dar pulled away, smiling. “I’ve brought another old friend,” he said. Maria followed the direction of his gesture. A woman with an unmistakably pregnant profile gingerly stretched her back, a handsome fair man at her elbow.

Maria took a few hesitant steps, searching the woman’s face.

“Mary?” asked Rose Red, at her elbow.

“Rosie! Maria!”

Mary hugged Maria, then Rose Red, then fell into Eurydice’s arms.

Maria, standing back and smiling, realized there weren’t so many people as she’d first thought, perhaps a dozen or so. She saw a young couple, an old couple and what looked like a mother and daughter. Her eyes were caught and held by a head of short golden hair.

“Rapunzel! Rapunzel!”

Rapunzel looked, eyes widening in recognition. She left her haggard-looking companion and met Maria. They hugged enormously.

“I can’t believe it!” Rapunzel said. “You cut your hair! You look wonderful!”

***

Evening found them grouped around the biggest fire they’d had yet. Maria looked around at the scene, feeling satisfied and proud of what they’d created. The horses grazed peacefully in a friendly clump, including Persephone and Demeter’s mounts. Carts parked here and there, blankets and sleeping rolls ready for the night.

A happy feeling of community and reunion embraced the group. Dar told a story with words and flute. Heks was a dark, neat shape beside Mary. Lugh sat in front of them, cross-legged, his cloak furled like jeweled wings around him and his earring catching the light. Rapunzel’s cropped gilt head was next to Cassandra, who looked up at Dar as he talked and played, gesticulating and pacing near the fire, bone flute and cloak glimmering.

An owl screeched, close behind Maria. It made her twitch with surprise. Dar stopped in midsentence and Lugh rose to his feet in a single motion of supple strength, head tilted alertly. He swung around, facing Maria, his back to the fire.

A pale shape, silent as a star, flew to his shoulder. In the moment of landing Lugh appeared to grow taller, his shoulders broader, the carriage of his head prouder. Maria never forgot the picture he made, a god of seed and harvest, the barbarically decorated cloak enhancing and underlining his maleness, with the white owl, blazing eyed, like a sculpture of snow on his shoulder.

Then the owl took off, silent as a blown dandelion seed.

“Good evening.”

A woman stepped out of the shadows, short-haired, lean, looking over a pair of silver-rimmed glasses.

Cassandra, with a wordless exclamation, threw herself into the stranger’s arms.