The Hanged Man: Part 4: Yule

Post #26: In which women create and share together ...

(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of The Hanged Man. If you prefer to read Part 4 in its entirety, go here. For the next serial post, go here.)

Minerva wove the wool into two generous yardages of midweight cloth, and it was time to begin dyeing.

Mary sat in the kitchen, having a bowl of soup while the twins slept, watching Minerva and Cassandra unearth the largest cooking kettles, when Cassandra swept her arm against a leaning pile of pots and pans and they fell clattering onto the stone floor.

“Wake,” she said, with an odd inward gaze Mary recognized. “She wakes, she lives, she wakes, she lives, she comes ever after…everything lost is found again.”

Mary heard Hecate answer a knock at the door.

They were still matching lids to pots and putting them away when Hecate brought the newcomer to the kitchen.

The strange woman’s gaze fell on the two cauldrons sitting ready on the table. “Good!” she exclaimed with pleasure. “I’m just in time.”

Cassandra approached her tentatively, like a shy child, a hand going to one of several braids plaited with a leather thong on which small brass bells trembled. The woman turned her head obligingly, so the braid hung within easy reach. An earring swung gently. Holding still so Cassandra might explore, the stranger met Minerva’s eyes, her own full of tears. “Minerva.”

“Briar Rose. My dear daughter. It’s good to see you again.” They smiled at one another.

“Silver fish in blossoming rose,” said Cassandra to Hecate, who stood in the doorway watching.

“I hope it’s careful of the thorns, then,” said Hecate seriously. Cassandra stopped caressing the bell-strung braid and turned away, losing interest.

“I’m Briar Rose,” said the newcomer to Mary. Unexpectedly, she stooped and kissed Mary warmly on the cheek. “I’ve come to help with the cloaks.”

Briar Rose sorted through her bundles, keeping one out, and Hecate took the rest away.

For some days, Briar Rose and Minerva worked like a pair of witches in the kitchen, heads bent over mortars and pestles and packages. Strange and occasionally unpleasant smells wafted through Yule House. Bits of dyed wool, each sample pointing to a needed adjustment in ingredients, timing or heat, littered the table top. Hecate’s amber-eyed wolf, coming to the back door in hopes of a tidbit, sneezed violently and retired in disgust, making them laugh.

At last the wool was transformed into several yards of crimson with body and depth, a joyous, heart-lifting color. The other length was dyed deep purple, nearly black in some light. It mingled shadows of grape, plum and fig. It was the color of storm clouds in autumn.

With this accomplished, they gathered to spread out gifts for the twins. Minerva and Briar Rose unpacked and laid out what they’d brought. Baubo held Dar, who watched everything gravely, but smiled for those he knew and trusted. Mary held Lugh, who wept and laughed with equal passion and recognized everyone as a friend.

Minerva laid out owl feathers wrapped carefully in a piece of linen. On seeing them, Mary took from a box the silver feather Blodeuwedd left at the window on the night of her labor and added it to the others.

“Flower face,” said Cassandra, picking it up. “White flower. Snow flower.”

“Blodeuwedd keeps you close, then,” Minerva said to Mary with satisfaction. Hecate smiled to herself.

The feathers were of many colors and Minerva laid them out in fans of white and cream, brown and grey. Dar’s eyes widened in wonder, and when Baubo picked up a grey feather and brushed it against his cheek he smiled.

“These for the purple cloak, I think,” Minerva said.

Briar Rose unfastened a large package containing many smaller bags and wrappings. These she unwrapped, one by one.

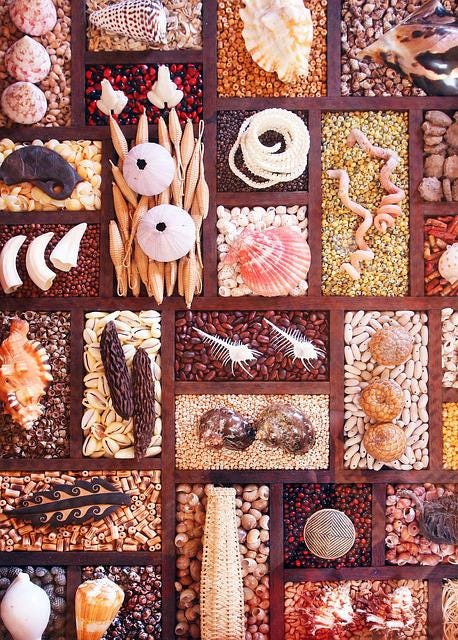

There were tiny bells of silver and brass. There were amber beads on a string, warm to the touch, smelling faintly of honey. They opened a package of carved bone and ivory beads. There were charms of silver, copper and brass in different shapes. There were shells like fingernails, pink and brown and cream. Wooden beads in every shade of brown and red were carved into beautiful patterns and shapes. Glass beads glowed and shone richly as they were revealed.

Minerva brought out two wooden boxes, plain and unadorned. They contained string after string of tiny pierced gems, jade, tiger’s eye, garnet, obsidian and amethyst. There were quartz beads and crystals.

As they stirred their fingers through this treasure, weighing, examining, exclaiming in delight at some minute bit of carving, Minerva talked of graceful foreign ships and merchants. Her workshop was in the port of Griffin Town, and she did business with travelers from all over the world. She also traded with the Dvorgs and Dwarves, those incomparable jewelers and metalworkers. Briar Rose entertained them with tales of crossroads and marketplaces, and peddlers carrying riches.

Cassandra reached out and touched a charm bracelet around Briar Rose’s wrist. “Wake,” she said. “Wake.” Briar Rose smiled at her. Minerva took off her glasses, sat back and told the story of how Briar Rose came to Yule House to lay treasure before them.

“Once upon a time past and coming again soon, there lived a king and queen who longed for a child.

The king was a proud man, anxious to make a fine show, and he feared people would think him weak and unmanly if he didn’t sire a child.

The queen spoke little, and as far as the king was concerned was quite perfect. She was beautiful, obedient, and a credit to him. She sat down at table with him, laid down at night with him, and rose in the mornings with him. She was a skilled weaver, spinning her own thread and coaxing marvelous colors out of herbs, roots, bark, and even insects. The other kings envied him his wife. If only they had a child!

While the King went about his duties, every day the queen and her most faithful attendant stole away to a pool in the forest.”

Minerva paused, an affectionate look passing between her and Briar Rose.

“The castle and its grounds were surrounded by a thick hedge of brambles and briars, and this pool lay in the forest just outside the hedge. The queen found an opening in the hedge and for many years had come to this secret place to bathe. The forest creatures knew her and took no notice of her presence. Indeed, she’d made quite a pet out of a frog living in the pool.

It came to pass that the queen at last bore a child, a lovely little girl. The king, beside himself with joy, ordered a feast to which he invited all his relatives, friends, and acquaintances. He took special care to invite all twelve fairies in his kingdom, and set a table apart for them. Their dishes were gold and crystal, their cloth the finest damask. Silver shone like glass and innumerable candles lit the scene. The fairies possessed the power to give the baby marvelous gifts, if they were properly encouraged by the richness of the king’s hospitality. (Naturally, each fairy would take away her place setting.)

One by one, the fairies rose and blessed the baby with perfect grace, happiness, health, and everything needed for a life of unblemished peace and joy. The company was impressed and the king felt satisfied. His daughter would be a perfect princess, a credit to him.

The queen, as usual, said nothing.

Suddenly, the door opened and in came an old woman in a plain hooded cloak with a stick in her hand. The company fell silent. It was the Wise Woman of the kingdom, who hadn’t received an invitation to the banquet.”

Minerva smiled sardonically. “It was you!” said Mary, catching on.

“Wait till you hear the curse!” said Briar Rose, chuckling.

“The crone hobbled over to the elaborate cradle where the baby lay. She bent and made a sign over the child.

‘Child,’ she said in a clear voice, ‘beautiful child, here’s my gift to you. You shall one day prick your finger on a spindle… and WAKE!’ She turned and shuffled back out the door.

A murmuring broke out among the throng. ‘What did she say?’ ‘What did she mean?’ The king turned to the queen, who looked wordlessly back at him. He hadn’t understood the old one’s words, but it seemed clear the child would be in danger from a spindle, so he ordered all spindles in the kingdom to be burned immediately, along with spinning wheels, distaffs and, for good measure, looms and shuttles. As an example, he made a public display of burning the queen’s spinning wheel and loom first.

As usual, the queen said nothing.

Years passed and the princess, who was called Briar Rose, grew in loveliness and was perfectly happy. She fell in love with the prince next door and they were married. Naturally, they conceived three handsome, strong, sons. However, the first son grew to be a wastrel and a gambler. The second son took to drink and chased women. The third son left one day to seek his fortune.

The prince, now king, was a proud man, anxious to make a fine show. He stayed busy with his kingly affairs.

Briar Rose, now queen, spoke little and, as far as the king was concerned, was quite perfect. She was beautiful, obedient, and a credit to him. She sat down at table with him, laid down at night with him, and rose in the mornings with him. Other men envied him his wife.

One day, while the king went about his duties, Briar Rose took one attendant, an old woman who’d served her mother before her, and they walked about the castle grounds. The hedge of brambles and briars was high and thick, but Briar Rose found an opening in it she’d never seen before. She followed a path to a forest pool. Longing for the water against her skin, she bathed. A frog squatted on a rock, watching her intently. She drew near to it and it jumped away, as though in play. Next to the place it sat lay an old key with scrollwork on its shoulders. It was encrusted with red gems. Wondering, Briar Rose took the key back to the castle with her.

As the king went about his daily duties, Briar Rose visited the forest pool every day. The days seemed long and the castle large and empty. Briar Rose climbed stairs and walked down corridors she couldn’t remember seeing before. She peered into empty rooms. One day, exploring the attics, she came across a locked door. The jeweled key was in her pocket; it fit the door and she opened it. There sat the old servant who accompanied her to the pool every day, in a shaft of sunlight at a whirring wheel. Briar Rose came close; she’d never seen a spinning wheel before. The old one deftly turned a wooden dowel in her hand. As though in a dream, Briar Rose reached forward to touch the spindle, and pricked her hand.

She learned to spin, dye the yarn, and weave. She collected feathers, hair, bones, snake skins, and twigs. In the market, she bought glass beads and charms of copper and silver. She planted an herb garden so as to make her own dyes, tended it barefoot, and went to bed late with grimy soles. In the market, she met a peddler, lean and dark, his face worn with weather and laughter. He played a bone flute. His haunting, insinuating melodies filled Briar Rose with longing.

The peddler presented her with a bracelet of bells for her ankle and one day, hearing the flute on the other side of the bramble hedge, she unbound her hair, picked up her skirts, and danced.

She caught a cold dancing under a summer full moon. Her chapped, red nose appalled the king. She’d never been ill before. Her transparent white skin freckled from sun. She flaunted the grey in her hair and the king felt ashamed of her. In the pool, Briar Rose traced silver lines of childbearing on her body, lifted her breasts, laughed and wept, and lay naked on moss to let sunlight touch her.

Briar Rose gave her weaving to the peddler. The pieces were strange, like nothing anyone had seen before. Bits of bone, owl feathers, animal hair, beads and bells and charms intermingled with texture and color, making people stare. The peddler made good money from selling them.

One day the king woke to find Briar Rose was gone.

The peddler broke her heart, of course, but she lived awake ever after.”

The babes slept. The women at the table held the story for some minutes in silence.

“Silver, gold,” Cassandra crooned to herself. “Gold, silver. Me, not me. Not me, silver…” She was sorting everything on the table into two piles.

“That’s right,” said Minerva. “Now it’s time to cut out the cloaks and make them. How shall we embellish purple and crimson?”

It wasn’t always easy to choose. Everyone but Cassandra wavered occasionally. In the end, they deferred to her judgment.

The next day they began, passing the cloaks back and forth as inspiration waxed and waned.

Days came and went, but Mary had no sense of time passing. She often left the house, stepping into winter’s silent embrace. Since the birth she’d felt slow and muffled in head as well as body.

She remembered the babies’ father, Lugh, sun dusted, laughing, gold earring glinting, his crimson cloak falling around strong thighs, rippling with agates, amber, gold thread and copper charms. She remembered how they’d lain together, wild, passionate, held in a net of flute and musky seed on the Night of Seeds. He was gone now, her lover, diminished, his blood and flesh gathered in with harvest in another turn of the wheel. As he poured himself out, her belly had swelled until she felt sure her skin would split. The loss and gain of it felt painfully satisfying.

As she wandered through winter landscape, Hecate’s wolf followed her. She wasn’t afraid of him. He never came near, but she glimpsed him across a snowy field or trotting between trees. He comforted her — there, but undemanding, needing nothing, a distant companion.

It seemed odd to make a new crimson cloak like Lugh’s for his son. More than odd, it was uncanny if she really thought about it. Lugh the lover, the father, was gone. He’d been swept away from her, lost somewhere behind, harvested, dried and threshed. Now his son began a new cycle.

Thinking, remembering, made her head ache. Dreams, past and future tangled hopelessly and she felt too apathetic to unravel them. It didn’t matter, in any case. Whatever had come before or would come after, now they were at Yule House making cloaks. It seemed enough to know.

One evening Cassandra, arms full of purple wool, ceased the low-voiced singsong nonsense chant she fell into when she felt peaceful.

“Poor silver fish! Sleeping silver fish!” She looked appealingly into one face after another, grouped around the work table where they sewed. The crimson cloak draped over the table between Baubo and Briar Rose, each of them at work on a different part.

Mary’s torpor was pierced. They’d all learned to keep calm and quiet, no matter what Cassandra said. Any display of distress exacerbated hers, but nothing upset her as much as ignoring her. Clinging, frantic, beseeching, she wept and babbled, increasingly incoherent, until assured the others heard and believed.

Cassandra had spoken of silver and gold fish ever since she’d come to Yule House. For some reason, this evening Cassandra’s distress was contagious and Mary felt sudden fear for Dar, solemn, sweet Dar with his considering gaze and hesitant smile.

She put down the pattern of leaves and flowers she was tracing for Lugh’s cloak.

“What do you mean?” she asked, more sharply than she intended. “What’s wrong with the silver fish? Why does he sleep?”

Cassandra began to tremble. The needle she held fell into the folds of wool in her lap.

“Little fish swims, and sleeps, and flies! He flies on silver wings, flies away, flies and dies, dies and flies!”

Mary looked at her, appalled, her face unguarded. Cassandra began to moan and rock. “Believe me!” she said. “Believe me!”

“Cassandra,” said Minerva, reaching out and capturing her wringing hands. “We believe you. You told us and we believe you. Remember, you don’t need to try to make things good. Remember the Holy Shadow? He made things good without trying.”

Hecate covered one of Mary’s stilled hands in her own. She rarely made gestures of physical affection and the surprise of it distracted Mary from her own distress. “Steady, Daughter,” she said in a low voice. “All is well.” Then, holding Cassandra’s anguished gaze with her own but speaking to the table at large, “I know that story, Cassandra. That’s an old story of past and future. Calm yourself, and I’ll tell it.”

Between Minerva’s touch and mention of the Holy Shadow, an oft-repeated tale Cassandra never tired of, she calmed. Mary took a deep breath and returned to her pattern. Baubo showed them a lion embroidered with gold thread and a mane of amber beads she was finishing on Lugh’s cloak. Minerva continued sorting crystals and pearls for a design of water, fish and stars around the hem of Dar’s cloak. Gradually, Cassandra relaxed.

“This tale is called ‘The Devil’s Cloak,’” Hecate began.

“Two babies, one silver, one gold, turn and stretch in the dark, rocked together in warm salty waves. Behind sealed eyelids, the silver infant dreams. Once upon a time and coming again soon is a moon dream of a silver fish swimming with stars. Once upon a time and coming again soon…

An old man sleeps in a cart in the desert. All his sunny days are etched around his eyes. All his miles are written on his soles. Each note he’s played on his flute gathers in seams around his mouth. He sleeps wrapped in the wings of his cloak.

In beginning and end, which were on the same day, imagine a flock of sheep, a season of shearing and carding, a journey to a great tree with three trunks. Imagine distaff, wheel and scissors in Fate’s hands, ageless and serpent wise.

At the end of another journey (and the beginning of the next), see wool woven on a loom strung of story, firelight, woman scent, turgid breast, pliant bone, salt and iron. The wool, now in two lengths, goes from loom to mephitic cauldron.

Now dyed, the wool is cut and shaped, stitched and embellished. The silver baby, birthed out of sunless womb’s ocean with his golden twin, now with fuzz of dark hair over his pearly head, receives a kingly purple cloak, a swirl of deep color, silver thread, feather and jewel, bone and charm.

The silver infant grows into a child. The child grows into a boy. The boy grows into a man who plays the road’s song on his bone flute while the cloak stirs in anticipation. Life’s circle hears the song and the rustle of the restless cloak. The circle cries out for them to take their place, man, flute, cloak.

They answer the call, man, flute, cloak. They leap into the circle. Life sweeps them into green and gold dance, dreams of silver and soot. A golden feather sewn on the cloak over the man’s shoulder blade dreams of being a wing. The feather’s dreams are copper, orange and crimson with hearts of green fire.

He mines for truth, the silver man. He drifts and whirls, cloak rippling in the flute’s song, like a star-struck spark that fears fire’s embrace. Sometimes he dreams old dreams of bare feet striding through desert sand under a froth of black hem, but he doesn’t remember those when he wakes. He’s a wanderer, chary of restraint. He can love but he won’t stay. Faintly on the wind, he hears his twin’s piping.

He discovers what he’s for.

The circle turns. Time wheels like a star along the vault of heaven. Man and cloak reflect life’s embrace. Lines settle in place where flesh was smooth. Embroidered threads weaken. Frost kisses dark hair. A charm loosens. Tongue and eye grow keen together and then gradually soften. A bead is lost. Youth dims. Hems thin. Injury and tear leave thickened scars on skin, heart and wool.

Spirit candles at sea. A queen who awakes. A woman with silvery golden hair. A young man with a twisted hip in search of himself. Outcasts and kings. Dancing Death and goat-foot Seed Bearer. Dwarve and maiden, hag and stag crowned with glowing bone. A Blue Witch in a light-struck tower. They all whirl in the circle with him, clasped to one another by story.

One day he discovers what lies beyond independence and ties himself gratefully with a golden rope that isn’t there. Brother unites with brother as harvest approaches. Feather on his shoulder still dreams of flying, but the bottom of the cloak is fringed with broken threads, hem unraveling and thin as cheesecloth.

The wheel turns and connection and community sustain him more than freedom ever did, but the road is still his oldest lover. Embroidery fades, crystal, bone and pearl drop like stardust in his wake. He shortens and shortens the cloak with his knife, trying to stay ahead of damage and wear.

During harvest of miles, days and stories, a day comes when the man is an old man in a ragged cloak with a shining golden feather on the shoulder. The feather dreams of becoming a wing.

Now, in end and beginning, an old man sleeps in a cart in the desert. A child with hair and eyes as dark as life-giving earth in a fertile flood plain opens the cart. The old man’s last dreaming breath comes to her, scented with exotic spice, early morning on a far-away city street, beckoning road after a rain at dawn, and she smiles, memories in her ageless eyes. The small weights of her earrings nestle against her neck. Easily, she lifts the old man in her arms, one of which is tattooed with dots, dashes and lozenges like a snake.

Tenderly, she lays the old man’s body down on the silk-rippled bed of the desert and stretches slender arms over him. Her arms become the pointed wings of a falcon and hide him from the stars. She sings a fierce song of hooked beak and bone, death cry and lament of lost things. The threads of the cloak sink into the sand, beads and charms and bells like drops of water. Only the glowing feather remains, a candle in the sand. The pointed wings raise gracefully and the sight of the old man’s naked body is greeted by the night sky with a silver spray of starry laughter. A shooting star, copper and orange with a heart of green fire, speeds across the sky, arrowing lower and lower over the desert. It flies under the pointed wings and takes up the frail body, unraveled and ragged, in its talons without pausing. The cloak’s feather drifts across the sand. The old man’s body is borne away into black sky over red desert, like a dream of flying.

As the child folds her wings and skips away into the desert night, the cart settles into the sand with a sound like a sigh.”

Mary wept.

(This post was published with this essay.)