The Hanged Man: Part 4: Yule (Entire)

In which you can read without interruption ...

CHAPTER 12

MARY

The pains began at twilight. In the light of candles, she sat at the window and watched night bid farewell to day. It was the longest night of the year. Deep within her, more powerful than her own will and strength, a great clenching pain gathered and rose and then broke, receding. It left her breathless, sitting quite still as though afraid if she moved it would find her again. It didn’t immediately return and she consciously relaxed, moving her hands over the taut skin of her belly, breathing as deeply as she could. She felt the chair supporting her, the floor under her feet, the fire’s heat pushing against her legs. Drops of water beaded the curved lip of a pitcher on the table. She’d always liked the shape of that pitcher with its graceful handle, glazed an earthy brown. She thought of the water it contained, cool and clean. In a minute, she’d pour some into a cup and drink. Then she’d begin to walk. In a minute. Now, though, she felt she could fall asleep, doze here in firelight with night’s elbows on the window ledge, breathing its cool breath into the room.

Hecate came in. Mary looked up and their eyes met. Hecate left, returning in a moment with an armful of fresh linens. She set them down and pulled the low birthing stool from against the wall to a place nearer the fire. She poured water and handed the cup to Mary. It tasted just as she’d imagined, cold and sweet. She drank thirstily. Hecate helped her out of the chair.

They walked. The moons rose. Hecate spoke, her voice ageless, sexless, like the voice of eternity. She spoke of cycle and wheel, the rise and fall of stars as seasons came and went and came again. Now and then pausing to add wood to the fire, she spoke of seed in dark ground, quickening, growth, bud, leaf, flower, fruit, falling leaves, harvest and seeds falling again to dark ground. They passed the loom in the corner and Hecate spoke of wool, flax, linen, hemp, spindle and distaff, loom’s warp and weft, dye, needle and silk. She spoke of inexorable tides ebbing and flowing, and Mary felt the echo within her and thought of two little fish caught in that tide, silver and gold, pulled irresistibly into life by birth’s current.

Night paused at the open window to be with her, cooling and comforting her labor. Stars were silver flowers of frost in the dark sky. Resting on the birthing stool, Mary looked up and saw a white owl at the window. Hecate welcomed it, inclining her head, and told its story as Mary labored.

“A tale is told of Llew, a mighty man, the son of kings. Llew couldn’t take up his mantle without a wife. It happened that Llew was cursed, so he was unable to possess a human wife. His two uncles, Math and Gwydion, were magicians. They were determined he should fulfill his kingship, and so together took the nine sacred flowers of primrose, cockle, bean, nettle, chestnut, hawthorn; the blossoms of oak, broom and meadowsweet, and created from them the fairest maiden man ever saw. They breathed life into her and called her Blodeuwedd, or Flower Face.

At the same time, they cast a spell to keep Llew from death, as they feared misadventure and treachery when he took his rightful place as king with a wife by his side.

The two magicians were proud of their work and instructed Blodeuwedd carefully in her duty as a fitting wife to Llew. But their pride was at once too little and too great, and they were careless of the power of the nine sacred flowers. Strength of oak; life of primrose; earth of bean; wild protection of nettle; love and magic of hawthorn and the sweet, healing scent of meadowsweet — all these created a Goddess of Spring, a woman entire, a wild woman, the White Lady, and she was not theirs to control and command. Her destiny was far greater than wife or lover.

So, Blodeuwedd did not love her husband, Llew.

She caught the eye of Goronwy the hunter, handsome and treacherous, and he desired her. She made him a tool with which to gain her freedom.

Blodeuwedd coaxed from Llew the secret of his protection from death, and so overcame the spell with the help of Goronwy.

She and Goronwy tried to kill Llew, but failed. Gravely wounded, Llew turned himself into an eagle and disappeared. As an eagle, he suffered until found many weeks later by his Uncle Gwydion, whose eyes looked past his shape and recognized his nephew, the king.

For many months Llew lay ill, passing death’s borders and then wheeling back into life. In the end, the king rose from his sickbed, made greater than whole by his dark journey, and ruled again.

Then Gwydion turned his thought to Blodeuwedd and punishment for her treachery.

A great chase began over mountains and rivers, until at last she stood at bay, proud and lovely.

Gwydion, terrible in righteous anger, said, ‘Be now a bird, and for shame you shall not show your face in the light of day. You shall keep your name, that all shall know you and your faithlessness and treachery!’ With his staff, he struck her and she flew up as an owl.

She rose in the air, heart bursting with joy. Free! Free from Goronwy and his weakness! Free from Llew, whom she had made a king among kings! Free in darkness and moonlight!

And so Blodeuwedd brushes the night with silent wings, communing with waxing and waning moons and tides. She is wisdom and fertility, mystery and prophecy of flowers in frost and frost on flowers.”

As the story ended the owl spread its wings in a soundless silver sweep and floated away, but Mary didn’t forget its queenly regard and the next day found a shining feather on the sill.

Now Hecate spoke to the unborn ones, little fish, silver and gold, calling them forward. Mary groaned, panted, breathed, drank cool water, felt held and comforted in Hecate’s words, leaning to rest in the old woman’s arms when rest there was.

Then there was no more rest. Pain held her, inexorable, huge. She pushed, felt herself stretch and open, stretch and open. In a pause, she opened her eyes and realized night had passed on, was even now embracing day. Pain once more took her in its own embrace and she pushed with all her strength and felt the child slide out of her into Hecate’s hands. The child was silver and shadow, grey eyes wide as though with wonder. Hecate tied off and cut the cord and wrapped him in clean linen. Mary held him, warm and slippery, against her. His heart beat quickly. She rested her cheek on his damp head, smelling the place within her whence he’d come. Once more pain clasped her and, holding her dark little boy, fresh from the water of another world, she gave birth to his brother, fair and ruddy and green eyed, and he roared with a sound like triumph with his first breath.

In the following days, Mary rested and her sons fed and slept and throve. Hecate cleaned and polished the birthing stool, blessed it, and took it away. A wide cradle stood in the room. Winter enfolded Yule House, where loom waited, fire burned, babies slept and nursed and slept again.

***

“Visitors,” said Hecate one afternoon. She stood aside for a brisk, elderly woman with a cap of short white hair and an armful of packages. A younger, smaller woman followed her. “Put those on the table, Minerva.”

As the newcomer did so, Hecate said to Mary, “This is Minerva, and this is Cassandra.”

Haunted brown eyes in a gaunt face framed by a riot of luxuriant brown hair met Mary’s for a moment before the woman looked away, managing to convey a flinch without moving a muscle.

Minerva’s sharp eyes were grey behind her spectacles. Dar looked up at her solemnly as she bent over Mary to inspect him. Minerva offered him a finger, and at once the tiny starfish hand grasped it. Minerva laughed.

“Congratulations, my dear. He’s beautiful. Come and see, Cassandra.”

“Deep-drinking roots where fish perch, silver and gold, silver and gold,” said Cassandra. “Mirmir whispered it to me.” She stood awkwardly, as though afraid to approach Mary.

“Mirmir knows all stories,” said Minerva.

“It’s not bad. I don’t need to stop fish swimming or roots drinking, do I, Minerva?”

“No, my daughter. You don’t need to stop anything, even if it is bad. I think you know you can’t always stop bad things.”

Cassandra’s face crumpled in bewilderment. “I do need to. If I know about something bad, I need to tell and try to make it stop. I must make them believe…”

“I know a wonderful story about that,” Hecate interrupted.

“Oh, I like stories!” Cassandra was diverted. “It’s not a bad story, is it?” she asked, frowning again.

“Shall we sit down? The babies might like to hear the story too.”

“Yes,” said Cassandra uncertainly, still motionless. Mary pulled herself to her feet, her deflated body awkward and sore. “Come and meet Lugh,” she said, taking Cassandra’s hand and leading her to the cradle.

“Silver and gold, silver and gold,” crooned Cassandra as Mary pushed the blankets aside.

“We call the silver one Dar and the gold one Lugh,” said Mary.

For a long moment, hazel eyes met brown in perfect understanding.

***

While Minerva strung the loom and unwrapped hanks of wool she’d brought, Cassandra had a hot drink and something to eat with Mary, who ate frequently throughout the day. Hecate poured a cup of tea for herself and settled into her chair by the fire.

“Were you going to tell a story, Hecate?” Minerva asked from the loom.

Hecate’s lips quirked. Cassandra put her hands in her lap like a good child. “It’s a small story about a magic man like you, Cassandra.

“There lived a man who was so good the Gods offered him the gift of miracles. Humbly, he refused the gift, but when pressed he asked that he be allowed to do a great deal of good without ever knowing it.

So, the man went about his life as he always had, doing each day’s tasks, and wherever his shadow fell behind him, it cured illness, soothed pain and comforted sorrow. His shadow brought green life to arid ground and springs of fresh bubbling water to the earth’s surface. He trailed joy wherever he passed, but he never looked back, so remained unaware of the blessing of his passing.”

“He trailed joy wherever he passed,” repeated Mary. “I like that.”

“He made things good and didn’t even try,” said Cassandra.

“They called him the Holy Shadow,” said Hecate.

***

“What are you making?” Mary asked Minerva respectfully. Hecate had told her of Minerva’s skill, her school and her business, but refused to say why she came to Yule House.

Minerva looked up from the loom, though her hands continued to weave. Her gaze sharpened over the top of her spectacles, which perched halfway down her nose.

“Every cycle I weave cloaks for twin boy babies born at Yule,” she said. “The Norns — you know of them, the three Fates who spin, wind and cut the fiber?”

“Yes. Cassandra mentioned Mirmir. Doesn’t he guard the well at Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, where the Norns live?”

“He does. The Norns and Mirmir are great friends. Well, the Norns prepare the wool and I weave it. Then we dye it and make the cloaks. It’s a kind of ritual, and it means I can take a vacation, play with babies, see old friends and students.”

“Lugh — I mean their father, Lugh,” Mary said, indicating the sleeping twins, “and his brother wore cloaks. They were beautiful. I wonder if you made those?”

“I did,” said Minerva.

“Oh,” said Mary, rather blankly. “Well…thank you.”

Humor gleamed on Minerva’s face. “My pleasure,” she said seriously.

While Minerva wove, Mary rested, rocked with a child at her breast or on her shoulder, half listening and half dreaming as Minerva and Hecate talked. Cassandra, on good days, helped Hecate with household work. Other days she clung to Minerva or Mary; Mary found an odd comfort in Cassandra’s presence.

Mary dozed, dreaming of wool woven out of firelight, frost and flake and star, cool taste of water, scent of baking bread, tart pomegranate on the tongue, the smell of baby diapers, thin sticky milk gulped eagerly from her heavy breasts and the feel of clean linen against her skin.

Cloth grew on the loom. Mary’s torn body healed. She ate with appetite. She felt content to drift and do nothing. Her mind felt weary. Something of herself had moved into the children as their lives were cut from hers. It wasn’t love. Love, a separate thing, rose endless within her for each babe as she held him, nursed him, noted the awakening of awareness. Not love, but some other vital essence of herself they’d taken into themselves. She no longer felt whole in the way she’d felt before. She felt a deep weariness and longing she couldn’t define or name. She wondered if the babies’ father felt this way before he and she parted, depleted even beyond the ability to care. She wanted to step back, step away, be still and quiet.

Her body, too, seemed no longer quite her own, no longer the familiar and trusted place she once knew. Silver threaded her hair and her skin would forever bear marks of childbearing and nursing. Back, hips, belly and thighs were suddenly strange to her. She understood for the first time the sacrifice demanded for new life.

She sat cradling the dark head and then the fair one at her breast and looked out the window, thinking about increase and decrease.

Into this time came Baubo, arriving on a sunless winter day. A second piece of cloth grew on the loom. Dar had nursed and rested against Cassandra’s shoulder, and Lugh nursed. The door opened and Baubo came into the room.

She was a figure to smile at, nearly as wide as she was tall. She wore shapeless and not very clean clothes, a skirt of rough homespun in drab brown and a tunic of grey. A tangle of curls grew from her pink scalp and she wore stockings, having left her cloak and boots at the door when Hecate welcomed her into Yule House. A hole in her left stocking revealed a dirty toe with a yellowed nail, much too long, poking out.

She walked straight to the rocking chair by the window and looked down at Lugh where he nursed. He’d just latched on and his greed had released the milk, but when he saw Baubo’s homely face and wide smile, he let go of the nipple and grinned up at her. Milk squirted against his cheek, wetting his mother’s clothes as well as his own gown, but Mary could do nothing about it. The sight of the old crone and the new babe, one so homely and well worn, one so fresh and new, grinning at one another was so ridiculous she snorted with laughter. The babe then transferred his gaze to his mother and chuckled, waving an arm towards her face, and she laughed harder, feeling the milky damp patch growing. She realized as she bubbled with laughter it had been a long time since she’d laughed. Baubo reached down and scooped the babe in his sticky gown into her own arms and Mary, now quite helpless with mirth, took a piece of linen from her shoulder and held it against her squirting breast to stop the flow of milk. She laughed and laughed and felt her breasts quiver and jiggle, one empty and slack, drained by Dar, and one heavy and uncomfortable with milk, felt the loose skin of her belly and the fat under it shake, and she didn’t care. She laughed anyway. Baubo and the babe laughed with her and then they were all laughing. Dar, held in the crook of Cassandra’s arm, looked around at the hilarity and joined in with his own chuckle, waving a fist in the air.

Order was restored. Hecate brought fresh tea, new bread and butter and soup. The unfed twin returned to the breast and this time drained it before joining his brother in slumber. Mary sponged herself clean and put on a fresh gown. Minerva showed Baubo her work on the loom.

Evening fell and Hecate lit candles and put more wood on the fire. Minerva left her weaving and joined the others by the hearth. Silence fell, content and easy.

“Tell a story,” said Cassandra to no one in particular.

“Yes, do,” agreed Mary.

“What about?” asked Minerva.

“Singing bones,” said Cassandra.

“Oh, yes,” said Minerva. “I haven’t shown you yet.” She groped under skeins of raw wool near the loom and came back to the fire with two objects in her hands.

“Oh,” said Mary in wonder.

Minerva handed her a bone flute, slender and curved to follow the original shape of the bone. One end blossomed in an ivory sculpture of petals, pierced with holes. The other end was cut off cleanly, bone end smoothed and plated with a collar of gold. There were bands of gold, too, down the length of the shaft in between regularly placed holes. Gems were inset in the thick end, topaz, garnet and tiger’s eye.

Cassandra examined the other flute. The bone was similar, but the mouthpiece and banding were of silver, and the gems pearl, crystal and moonstone. “Singing bones,” she said dreamily, “sand and ice and cavern.”

“That’s right,” said Minerva. “Nephthys began it.”

“Lost and found, lost and found…” chanted Cassandra to herself. Then, to Minerva, “Tell about Nephthys.”

“Yes, please do,” said Mary, wondering who Nephthys was.

The others murmured assent. Hecate rose from her place and fed the fire. The women watched in silence as fresh logs caught and burned. Minerva began to speak.

“Like a pimple on a flat cheek, a ruined stone cistern erupts from horizontal, featureless desert. It’s been there a long time. Sun bleached and crumbling, part of a rounded side still stands amid fallen rubble, creating a rough cave.

Nothing moves in the sky over the cistern. The desert exhales in shimmering waves.

A woman sits in the shade of the curved wall amid the fallen blocks of stone. Her eyes are empty. The place stinks with the eye-watering smell of urine and feces. The woman has sores around her lips and her hair is a dirty no-color snarl. Her shapeless clothing is the same color as the desert. Sun glares like a hot, hard headache. For a long time, nothing changes.

Then, a vulture wheels a long way above the desert. A long way distant in that blank landscape an upright figure makes its way slowly toward the tank.

An hour, a day, three days later, a vulture floats in the sky on the desert’s warm breath. The approaching figure is a female child, breasts just beginning to bud. Her hair is a thick dark cloud. She’s creased with sand and wears nothing but a ragged strip of cloth about her middle and dangling gold earrings. A tattooed series of dots, dashes and lozenges curls about her left arm like a snake. She’s dried and hardened by the desert, an old woman child with ageless eyes that are black as the life-growing earth of the flood plain. She carries a bundle strapped on her back and a grimy bag around her neck.

She reaches the ruined cistern. Inside it, Lost Woman goes on being lost. Nephthys reaches in, takes her by the arm and hauls her onto the sand. Lost Woman stands there, caked in her own filth and wrapped in stench. She says no word, makes no move. Her gaze rests incuriously on the child.

Nephthys doesn’t speak, for Lost Woman is lost and can’t be found with words. They’ve lost their power to call her.

With a few deft movements, Nephthys releases Lost Woman from her clothing and lets it fall onto the clean sand. She sees scars, foul open sores, shrunken withered breasts, a fleshless scaffold of bones. She pulls Lost Woman down to kneel, stoops and fills her hands with clean, bright sand and begins to wash Lost Woman gently. Starting at her neck, she rubs in slow, delicate circles with handfuls of sand. It falls down Lost Woman's thin back, sifts into the cleft of her buttocks, dusts fine hairs on her body. As Nephthys works down her body, she pulls Lost Woman back to her feet. The child rubs away filth from hips and buttocks and legs. She polishes scars. She rubs every crease and sag and fold of skin. She washes elbow creases and under arms. She cleanses inner thighs, behind knees, around delicate ankles. She rubs between each toe, the arch of each foot, between each finger and around brittle wrists. It takes a long time. She rubs away all that’s come before. She goes carefully around each open sore.

Once again tugging on Lost Woman’s hand to make her sit in the sand, the child rubs Lost Woman's face. With the lightest touch, she rubs forehead, temples, nose and cheeks. She rubs around sores about the mouth. She rubs the lips themselves, behind the ears, the chin. As she works on Lost Woman's face and looks into her eyes, something quickens in their empty depths. Something fragile looks out and Lost Woman’s eyes are no longer quite so empty.

Nephthys steps away, dusting her hands together and then clapping with satisfaction. Lost Woman stands obediently at the child’s gesture, and Nephthys drops to her knees in front of Lost Woman and puts her mouth to a sore above her right knee. Her mouth is as gentle and cool as a river in the sore place. She licks the wound. She moves around Lost Woman's body, first on her knees and then on her feet. She searches for every sore and scar and puts her mouth on each in turn, kissing, licking. It takes a long time.

Lost Woman, utterly naked in the foulness of her wounds, begins to weep. She weeps without sound and tears fall down her face, drip from her chin, fall onto her withered breasts, and fall onto the child. And there’s water in the desert as Nephthys cools the lost one's wounds, holds them in her mouth, licks them with long strokes, bathing each hurt in attention and reverence.

An hour, a day, three days later, a vulture flies high above on the warm desert’s breath. Lost Woman is sand polished and kissed back into the possibility of life. The white sky blazes. Nephthys reaches into her bundle and brings out several cooked eggs, wrapped in cool, moist leaves. She gives the eggs, one by one, to Lost Woman, who peels them and eats.

Nephthys takes from her bundle a folded square of stiff cloth, olive green, and hands it to Lost Woman, and then she turns her back on the empty tank and walks away. After a moment, Lost Woman follows her.

As they walk, the old cistern falls farther and farther behind. Once more, the desert looks empty. Neither looks back. The child walks steadily, strongly, as though on a path instead of endless sand. Lost Woman feels sun and air on her new skin, on open sores. She feels muscles stretch in her legs and feet as she walks in the sand. She feels herself breathing. Nephthys walks on and the lost one follows her.

An hour, a day, three days later, nothing stirs in the white sky. Nephthys is on her knees, scooping away sand with her hands. Lost Woman crouches beside her and puts out a tentative hand to the uncovered shape. It’s a bone, gently curved. Lost Woman picks it up and feels its strength and lightness. It’s cool from lying buried in sand. The shape of it in her hand reminds her of an old memory of cupping her own breast, firm weight of her flesh, nipple thrusting against her palm. The child unfolds the green square of cloth and knots three corners together. She gestures to the bone. Lost Woman puts it into the knotted pouch. Nephthys hands her the unknotted corner and walks on.

An hour, a day, three days later, two upright figures walk in the desert. Each drags behind her a rough pouch of heavy olive-green cloth loaded with bones. The bones are of every shape and size, some old and brittle and some new and hard.

Sometimes there’s been food and sometimes there’s been water. Sometimes there’s been sleep and dark desert sky. Sometimes a vulture circles lazily high above them in the white sky on the desert's breath.

Lost Woman sees life in the desert. The sand tells the stories of those who move upon it. Delicate footprints, beautiful curved trail of a snake and drag of a lizard’s tail whisper of life in this place. Sometimes a trail of footprints ends with a wing’s brush mark.

The child sees every trace of movement recorded in the sand. She reads a dropped feather, a shed skin and a tuft of hair caught on a thorn like a map. She collects seeds when plants offer them and puts them carefully into the bag around her neck. She follows the high paths of kite and vulture. A woodpecker drumming in cactus, the place where the grouse has taken a dust bath and the harsh language of the raven speak to her. The desert is utterly trackless to Lost Woman's eyes, but Nephthys moves over it with confidence and familiarity.

Lost Woman has watched Nephthys play with desert dogs and sand cats, dance with spiders and race snakes. She’s watched her gold earrings sway, glinting and shimmering like warm stars as she skips over the desert. She’s seen the smooth childish back with its round bumps of spine under a thick wiry tangle of dark hair and pointed wings outspread like arms over the desert, then woken from a sun-drunk doze and thought the vision for a dream.

On some nights, clear and cold and crowded with sharp stars, Lost Woman awakens and Nephthys isn’t there. The fire burns low and she feels safe. The night desert vibrates with life. A great heart lies underneath the smooth flanks of sand, beating steadily and slowly, intermingled with light, rapid pulses of many other lives. Movement and breath are about her. Sand shifts and murmurs. Wings are in the air. Coyotes howl in the distance. Her breath and heartbeat are part of the night song. She’s alive. She’s in the desert. She’s alive in the desert.

Every place they go there are bones. Some lie clean and bleached in the sand and some are buried and hidden. Many are broken and many are so small Lost Woman wonders how they ever came to be found at all. Most of the bones go in Nephthys’s pouch but now and then she hands a bone to Lost Woman and with each one Lost Woman is a little more found.

A finger bone reminds her of picking pine nuts. She puts the bone in her pouch and all morning, as she walks, she remembers the smell of dusty hot pinons. She can see their squat bushy shapes, feel the smooth small nuts in her hands.

The memory is like water in the desert.

A hip bone like a wing tells an old story about a strong young woman who stood upright with shoulders back. She remembers the stretched feeling after a night of love a little too big to be held between her thighs. She remembers the ache of a long walk in the autumn and the smell of leaves underfoot. She remembers a loose tired feeling of pain wrapped about her body like a blanket, the smell of blood, the weight of a baby in the crook of her arm.

They gather bones. Lost Woman learns how to sieve desert sands. Bones call out to her and she hears.

An hour, a day, three days later, the land changes and they come to a winding canyon. They walk along its floor, dragging their knotted pouches of bones behind them. Canyon walls rise gently as they walk, giving shade. After a while they climb, hauling their pouches after them. Nephthys leads them to a dark slit in the canyon wall that seems too small to enter, but enter they do, the child and the other behind her.

The cave widens out. A rough fireplace lies under a hole in the rock roof where a shaft of light comes in. A heap of skins nestles against a wall. Water from a spring trickles into a natural stone basin and drains away again.

There’s water in the desert.

They work together, and an hour, a day, three days later, a fire burns. There’s been food and drink and the blessing of bathing. Lost Woman’s sores are nearly healed and tell an old story now. She sits on an animal skin with another draped over her shoulders.

Nephthys unknots her pouch and spreads its contents on the floor, revealing her collection of bones. She smooths a large area of sandy floor with a twig broom and begins to lay out the bones. Fire burns. Night desert sky looks down. Time is not present. Nephthys murmurs, a child at play. She hums a lullaby, a prayer. She chants in a low whisper. Beneath her small, callused hands, white landscapes begin to take shape. There are what might be a mouse, a wild dog and the slender, weightless frame of a bird. Watching her, listening to the sound of her voice, Lost Woman sinks into a kind of dream.

Without thought, she goes to the pouch she’s dragged through the desert. She smooths another place on the sandy floor with the twig broom, and then, one by one, she puts the bones down and builds…she builds…oh, she builds…

Everything lost is found again. Her voice is found again. She lays out her vibrating bones and, to help them, to call and claim them, she takes a breath and sound flows through her and hums out her mouth, out her nose. The joints in her body loosen and sound fills her. She opens her lips and song swells and overflows, rising up her throat. Shapes under her hands tell her where the bones belong and she lays them there, one after another. Her song fills the cave and Nephthys picks it up, joins with it, supports it and lifts it, and they sing, Lady of Bones and Lost Woman, and the bones under Lost Woman's hands bind themselves together with cartilage and tendon and muscle.

The song goes on and deepens and the bones cover themselves with flesh and then skin, and there are breast and belly and hip and moist cleft between the legs. There is thick cinnamon hair and beauty and strength. The song beats like great wings against the ceiling and walls while Lost Woman puts her mouth to the mouth of the creature she’s made, presses herself against her and into her, and the woman opens her eyes, chest rising and falling with breath. The song finds the cave entrance and rushes out on falcon’s wings, wild and free, holding the women within it, and Lost Woman is found, soaring back into herself, into life.”

They were singing, a wordless tumult of passionate sound rising slowly to a triumphant crescendo of clapping and stamping and full-bodied voices holding nothing back. Mary saw tears on Baubo’s face. Gradually, the song fell away, quieted, softened, until it sheltered under their tongues and in the back of their mouths, humming and ebbing and then drifting into rich, firelit silence.

That night, when Mary slept, she dreamt of singing bones.

***

Minerva wove the wool into two generous yardages of midweight cloth, and it was time to begin dyeing.

Mary sat in the kitchen, having a bowl of soup while the twins slept, watching Minerva and Cassandra unearth the largest cooking kettles, when Cassandra swept her arm against a leaning pile of pots and pans and they fell clattering onto the stone floor.

“Wake,” she said, with an odd inward gaze Mary recognized. “She wakes, she lives, she wakes, she lives, she comes ever after…everything lost is found again.”

Mary heard Hecate answer a knock at the door.

They were still matching lids to pots and putting them away when Hecate brought the newcomer to the kitchen.

The strange woman’s gaze fell on the two cauldrons sitting ready on the table. “Good!” she exclaimed with pleasure. “I’m just in time.”

Cassandra approached her tentatively, like a shy child, a hand going to one of several braids plaited with a leather thong on which small brass bells trembled. The woman turned her head obligingly, so the braid hung within easy reach. An earring swung gently. Holding still so Cassandra might explore, the stranger met Minerva’s eyes, her own full of tears. “Minerva.”

“Briar Rose. My dear daughter. It’s good to see you again.” They smiled at one another.

“Silver fish in blossoming rose,” said Cassandra to Hecate, who stood in the doorway watching.

“I hope it’s careful of the thorns, then,” said Hecate seriously. Cassandra stopped caressing the bell-strung braid and turned away, losing interest.

“I’m Briar Rose,” said the newcomer to Mary. Unexpectedly, she stooped and kissed Mary warmly on the cheek. “I’ve come to help with the cloaks.”

Briar Rose sorted through her bundles, keeping one out, and Hecate took the rest away.

For some days, Briar Rose and Minerva worked like a pair of witches in the kitchen, heads bent over mortars and pestles and packages. Strange and occasionally unpleasant smells wafted through Yule House. Bits of dyed wool, each sample pointing to a needed adjustment in ingredients, timing or heat, littered the table top. Hecate’s amber-eyed wolf, coming to the back door in hopes of a tidbit, sneezed violently and retired in disgust, making them laugh.

At last the wool was transformed into several yards of crimson with body and depth, a joyous, heart-lifting color. The other length was dyed deep purple, nearly black in some light. It mingled shadows of grape, plum and fig. It was the color of storm clouds in autumn.

With this accomplished, they gathered to spread out gifts for the twins. Minerva and Briar Rose unpacked and laid out what they’d brought. Baubo held Dar, who watched everything gravely, but smiled for those he knew and trusted. Mary held Lugh, who wept and laughed with equal passion and recognized everyone as a friend.

Minerva laid out owl feathers wrapped carefully in a piece of linen. On seeing them, Mary took from a box the silver feather Blodeuwedd left at the window on the night of her labor and added it to the others.

“Flower face,” said Cassandra, picking it up. “White flower. Snow flower.”

“Blodeuwedd keeps you close, then,” Minerva said to Mary with satisfaction. Hecate smiled to herself.

The feathers were of many colors and Minerva laid them out in fans of white and cream, brown and grey. Dar’s eyes widened in wonder, and when Baubo picked up a grey feather and brushed it against his cheek he smiled.

“These for the purple cloak, I think,” Minerva said.

Briar Rose unfastened a large package containing many smaller bags and wrappings. These she unwrapped, one by one.

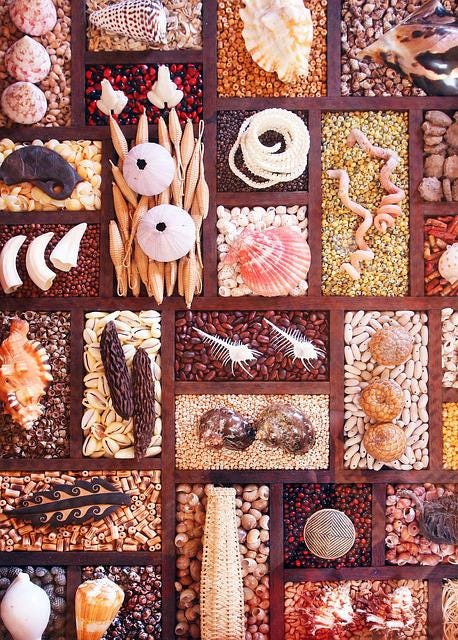

There were tiny bells of silver and brass. There were amber beads on a string, warm to the touch, smelling faintly of honey. They opened a package of carved bone and ivory beads. There were charms of silver, copper and brass in different shapes. There were shells like fingernails, pink and brown and cream. Wooden beads in every shade of brown and red were carved into beautiful patterns and shapes. Glass beads glowed and shone richly as they were revealed.

Minerva brought out two wooden boxes, plain and unadorned. They contained string after string of tiny pierced gems, jade, tiger’s eye, garnet, obsidian and amethyst. There were quartz beads and crystals.

As they stirred their fingers through this treasure, weighing, examining, exclaiming in delight at some minute bit of carving, Minerva talked of graceful foreign ships and merchants. Her workshop was in the port of Griffin Town, and she did business with travelers from all over the world. She also traded with the Dvorgs and Dwarves, those incomparable jewelers and metalworkers. Briar Rose entertained them with tales of crossroads and marketplaces, and peddlers carrying riches.

Cassandra reached out and touched a charm bracelet around Briar Rose’s wrist. “Wake,” she said. “Wake.” Briar Rose smiled at her. Minerva took off her glasses, sat back and told the story of how Briar Rose came to Yule House to lay treasure before them.

“Once upon a time past and coming again soon, there lived a king and queen who longed for a child.

The king was a proud man, anxious to make a fine show, and he feared people would think him weak and unmanly if he didn’t sire a child.

The queen spoke little, and as far as the king was concerned was quite perfect. She was beautiful, obedient, and a credit to him. She sat down at table with him, laid down at night with him, and rose in the mornings with him. She was a skilled weaver, spinning her own thread and coaxing marvelous colors out of herbs, roots, bark, and even insects. The other kings envied him his wife. If only they had a child!

While the King went about his duties, every day the queen and her most faithful attendant stole away to a pool in the forest.”

Minerva paused, an affectionate look passing between her and Briar Rose.

“The castle and its grounds were surrounded by a thick hedge of brambles and briars, and this pool lay in the forest just outside the hedge. The queen found an opening in the hedge and for many years had come to this secret place to bathe. The forest creatures knew her and took no notice of her presence. Indeed, she’d made quite a pet out of a frog living in the pool.

It came to pass that the queen at last bore a child, a lovely little girl. The king, beside himself with joy, ordered a feast to which he invited all his relatives, friends, and acquaintances. He took special care to invite all twelve fairies in his kingdom, and set a table apart for them. Their dishes were gold and crystal, their cloth the finest damask. Silver shone like glass and innumerable candles lit the scene. The fairies possessed the power to give the baby marvelous gifts, if they were properly encouraged by the richness of the king’s hospitality. (Naturally, each fairy would take away her place setting.)

One by one, the fairies rose and blessed the baby with perfect grace, happiness, health, and everything needed for a life of unblemished peace and joy. The company was impressed and the king felt satisfied. His daughter would be a perfect princess, a credit to him.

The queen, as usual, said nothing.

Suddenly, the door opened and in came an old woman in a plain hooded cloak with a stick in her hand. The company fell silent. It was the Wise Woman of the kingdom, who hadn’t received an invitation to the banquet.”

Minerva smiled sardonically. “It was you!” said Mary, catching on.

“Wait till you hear the curse!” said Briar Rose, chuckling.

“The crone hobbled over to the elaborate cradle where the baby lay. She bent and made a sign over the child.

‘Child,’ she said in a clear voice, ‘beautiful child, here’s my gift to you. You shall one day prick your finger on a spindle… and WAKE!’ She turned and shuffled back out the door.

A murmuring broke out among the throng. ‘What did she say?’ ‘What did she mean?’ The king turned to the queen, who looked wordlessly back at him. He hadn’t understood the old one’s words, but it seemed clear the child would be in danger from a spindle, so he ordered all spindles in the kingdom to be burned immediately, along with spinning wheels, distaffs and, for good measure, looms and shuttles. As an example, he made a public display of burning the queen’s spinning wheel and loom first.

As usual, the queen said nothing.

Years passed and the princess, who was called Briar Rose, grew in loveliness and was perfectly happy. She fell in love with the prince next door and they were married. Naturally, they conceived three handsome, strong, sons. However, the first son grew to be a wastrel and a gambler. The second son took to drink and chased women. The third son left one day to seek his fortune.

The prince, now king, was a proud man, anxious to make a fine show. He stayed busy with his kingly affairs.

Briar Rose, now queen, spoke little and, as far as the king was concerned, was quite perfect. She was beautiful, obedient, and a credit to him. She sat down at table with him, laid down at night with him, and rose in the mornings with him. Other men envied him his wife.

One day, while the king went about his duties, Briar Rose took one attendant, an old woman who’d served her mother before her, and they walked about the castle grounds. The hedge of brambles and briars was high and thick, but Briar Rose found an opening in it she’d never seen before. She followed a path to a forest pool. Longing for the water against her skin, she bathed. A frog squatted on a rock, watching her intently. She drew near to it and it jumped away, as though in play. Next to the place it sat lay an old key with scrollwork on its shoulders. It was encrusted with red gems. Wondering, Briar Rose took the key back to the castle with her.

As the king went about his daily duties, Briar Rose visited the forest pool every day. The days seemed long and the castle large and empty. Briar Rose climbed stairs and walked down corridors she couldn’t remember seeing before. She peered into empty rooms. One day, exploring the attics, she came across a locked door. The jeweled key was in her pocket; it fit the door and she opened it. There sat the old servant who accompanied her to the pool every day, in a shaft of sunlight at a whirring wheel. Briar Rose came close; she’d never seen a spinning wheel before. The old one deftly turned a wooden dowel in her hand. As though in a dream, Briar Rose reached forward to touch the spindle, and pricked her hand.

She learned to spin, dye the yarn, and weave. She collected feathers, hair, bones, snake skins, and twigs. In the market, she bought glass beads and charms of copper and silver. She planted an herb garden so as to make her own dyes, tended it barefoot, and went to bed late with grimy soles. In the market, she met a peddler, lean and dark, his face worn with weather and laughter. He played a bone flute. His haunting, insinuating melodies filled Briar Rose with longing.

The peddler presented her with a bracelet of bells for her ankle and one day, hearing the flute on the other side of the bramble hedge, she unbound her hair, picked up her skirts, and danced.

She caught a cold dancing under a summer full moon. Her chapped, red nose appalled the king. She’d never been ill before. Her transparent white skin freckled from sun. She flaunted the grey in her hair and the king felt ashamed of her. In the pool, Briar Rose traced silver lines of childbearing on her body, lifted her breasts, laughed and wept, and lay naked on moss to let sunlight touch her.

Briar Rose gave her weaving to the peddler. The pieces were strange, like nothing anyone had seen before. Bits of bone, owl feathers, animal hair, beads and bells and charms intermingled with texture and color, making people stare. The peddler made good money from selling them.

One day the king woke to find Briar Rose was gone.

The peddler broke her heart, of course, but she lived awake ever after.”

The babes slept. The women at the table held the story for some minutes in silence.

“Silver, gold,” Cassandra crooned to herself. “Gold, silver. Me, not me. Not me, silver…” She was sorting everything on the table into two piles.

“That’s right,” said Minerva. “Now it’s time to cut out the cloaks and make them. How shall we embellish purple and crimson?”

It wasn’t always easy to choose. Everyone but Cassandra wavered occasionally. In the end, they deferred to her judgment.

The next day they began, passing the cloaks back and forth as inspiration waxed and waned.

Days came and went, but Mary had no sense of time passing. She often left the house, stepping into winter’s silent embrace. Since the birth she’d felt slow and muffled in head as well as body.

She remembered the babies’ father, Lugh, sun dusted, laughing, gold earring glinting, his crimson cloak falling around strong thighs, rippling with agates, amber, gold thread and copper charms. She remembered how they’d lain together, wild, passionate, held in a net of flute and musky seed on the Night of Seeds. He was gone now, her lover, diminished, his blood and flesh gathered in with harvest in another turn of the wheel. As he poured himself out, her belly had swelled until she felt sure her skin would split. The loss and gain of it felt painfully satisfying.

As she wandered through winter landscape, Hecate’s wolf followed her. She wasn’t afraid of him. He never came near, but she glimpsed him across a snowy field or trotting between trees. He comforted her — there, but undemanding, needing nothing, a distant companion.

It seemed odd to make a new crimson cloak like Lugh’s for his son. More than odd, it was uncanny if she really thought about it. Lugh the lover, the father, was gone. He’d been swept away from her, lost somewhere behind, harvested, dried and threshed. Now his son began a new cycle.

Thinking, remembering, made her head ache. Dreams, past and future tangled hopelessly and she felt too apathetic to unravel them. It didn’t matter, in any case. Whatever had come before or would come after, now they were at Yule House making cloaks. It seemed enough to know.

One evening Cassandra, arms full of purple wool, ceased the low-voiced singsong nonsense chant she fell into when she felt peaceful.

“Poor silver fish! Sleeping silver fish!” She looked appealingly into one face after another, grouped around the work table where they sewed. The crimson cloak draped over the table between Baubo and Briar Rose, each of them at work on a different part.

Mary’s torpor was pierced. They’d all learned to keep calm and quiet, no matter what Cassandra said. Any display of distress exacerbated hers, but nothing upset her as much as ignoring her. Clinging, frantic, beseeching, she wept and babbled, increasingly incoherent, until assured the others heard and believed.

Cassandra had spoken of silver and gold fish ever since she’d come to Yule House. For some reason, this evening Cassandra’s distress was contagious and Mary felt sudden fear for Dar, solemn, sweet Dar with his considering gaze and hesitant smile.

She put down the pattern of leaves and flowers she was tracing for Lugh’s cloak.

“What do you mean?” she asked, more sharply than she intended. “What’s wrong with the silver fish? Why does he sleep?”

Cassandra began to tremble. The needle she held fell into the folds of wool in her lap.

“Little fish swims, and sleeps, and flies! He flies on silver wings, flies away, flies and dies, dies and flies!”

Mary looked at her, appalled, her face unguarded. Cassandra began to moan and rock. “Believe me!” she said. “Believe me!”

“Cassandra,” said Minerva, reaching out and capturing her wringing hands. “We believe you. You told us and we believe you. Remember, you don’t need to try to make things good. Remember the Holy Shadow? He made things good without trying.”

Hecate covered one of Mary’s stilled hands in her own. She rarely made gestures of physical affection and the surprise of it distracted Mary from her own distress. “Steady, Daughter,” she said in a low voice. “All is well.” Then, holding Cassandra’s anguished gaze with her own but speaking to the table at large, “I know that story, Cassandra. That’s an old story of past and future. Calm yourself, and I’ll tell it.”

Between Minerva’s touch and mention of the Holy Shadow, an oft-repeated tale Cassandra never tired of, she calmed. Mary took a deep breath and returned to her pattern. Baubo showed them a lion embroidered with gold thread and a mane of amber beads she was finishing on Lugh’s cloak. Minerva continued sorting crystals and pearls for a design of water, fish and stars around the hem of Dar’s cloak. Gradually, Cassandra relaxed.

“This tale is called ‘The Devil’s Cloak,’” Hecate began.

“Two babies, one silver, one gold, turn and stretch in the dark, rocked together in warm salty waves. Behind sealed eyelids, the silver infant dreams. Once upon a time and coming again soon is a moon dream of a silver fish swimming with stars. Once upon a time and coming again soon…

An old man sleeps in a cart in the desert. All his sunny days are etched around his eyes. All his miles are written on his soles. Each note he’s played on his flute gathers in seams around his mouth. He sleeps wrapped in the wings of his cloak.

In beginning and end, which were on the same day, imagine a flock of sheep, a season of shearing and carding, a journey to a great tree with three trunks. Imagine distaff, wheel and scissors in Fate’s hands, ageless and serpent wise.

At the end of another journey (and the beginning of the next), see wool woven on a loom strung of story, firelight, woman scent, turgid breast, pliant bone, salt and iron. The wool, now in two lengths, goes from loom to mephitic cauldron.

Now dyed, the wool is cut and shaped, stitched and embellished. The silver baby, birthed out of sunless womb’s ocean with his golden twin, now with fuzz of dark hair over his pearly head, receives a kingly purple cloak, a swirl of deep color, silver thread, feather and jewel, bone and charm.

The silver infant grows into a child. The child grows into a boy. The boy grows into a man who plays the road’s song on his bone flute while the cloak stirs in anticipation. Life’s circle hears the song and the rustle of the restless cloak. The circle cries out for them to take their place, man, flute, cloak.

They answer the call, man, flute, cloak. They leap into the circle. Life sweeps them into green and gold dance, dreams of silver and soot. A golden feather sewn on the cloak over the man’s shoulder blade dreams of being a wing. The feather’s dreams are copper, orange and crimson with hearts of green fire.

He mines for truth, the silver man. He drifts and whirls, cloak rippling in the flute’s song, like a star-struck spark that fears fire’s embrace. Sometimes he dreams old dreams of bare feet striding through desert sand under a froth of black hem, but he doesn’t remember those when he wakes. He’s a wanderer, chary of restraint. He can love but he won’t stay. Faintly on the wind, he hears his twin’s piping.

He discovers what he’s for.

The circle turns. Time wheels like a star along the vault of heaven. Man and cloak reflect life’s embrace. Lines settle in place where flesh was smooth. Embroidered threads weaken. Frost kisses dark hair. A charm loosens. Tongue and eye grow keen together and then gradually soften. A bead is lost. Youth dims. Hems thin. Injury and tear leave thickened scars on skin, heart and wool.

Spirit candles at sea. A queen who awakes. A woman with silvery golden hair. A young man with a twisted hip in search of himself. Outcasts and kings. Dancing Death and goat-foot Seed Bearer. Dwarve and maiden, hag and stag crowned with glowing bone. A Blue Witch in a light-struck tower. They all whirl in the circle with him, clasped to one another by story.

One day he discovers what lies beyond independence and ties himself gratefully with a golden rope that isn’t there. Brother unites with brother as harvest approaches. Feather on his shoulder still dreams of flying, but the bottom of the cloak is fringed with broken threads, hem unraveling and thin as cheesecloth.

The wheel turns and connection and community sustain him more than freedom ever did, but the road is still his oldest lover. Embroidery fades, crystal, bone and pearl drop like stardust in his wake. He shortens and shortens the cloak with his knife, trying to stay ahead of damage and wear.

During harvest of miles, days and stories, a day comes when the man is an old man in a ragged cloak with a shining golden feather on the shoulder. The feather dreams of becoming a wing.

Now, in end and beginning, an old man sleeps in a cart in the desert. A child with hair and eyes as dark as life-giving earth in a fertile flood plain opens the cart. The old man’s last dreaming breath comes to her, scented with exotic spice, early morning on a far-away city street, beckoning road after a rain at dawn, and she smiles, memories in her ageless eyes. The small weights of her earrings nestle against her neck. Easily, she lifts the old man in her arms, one of which is tattooed with dots, dashes and lozenges like a snake.

Tenderly, she lays the old man’s body down on the silk-rippled bed of the desert and stretches slender arms over him. Her arms become the pointed wings of a falcon and hide him from the stars. She sings a fierce song of hooked beak and bone, death cry and lament of lost things. The threads of the cloak sink into the sand, beads and charms and bells like drops of water. Only the glowing feather remains, a candle in the sand. The pointed wings raise gracefully and the sight of the old man’s naked body is greeted by the night sky with a silver spray of starry laughter. A shooting star, copper and orange with a heart of green fire, speeds across the sky, arrowing lower and lower over the desert. It flies under the pointed wings and takes up the frail body, unraveled and ragged, in its talons without pausing. The cloak’s feather drifts across the sand. The old man’s body is borne away into black sky over red desert, like a dream of flying.

As the child folds her wings and skips away into the desert night, the cart settles into the sand with a sound like a sigh.”

Mary wept.

MIRMIR

The Hanged Man rocked in Mirmir’s sinuous grasp while a grieving wind wound among Yggdrasil’s branches. “Dar! You tell of our birth and his death in the same story?”

“Birth and death are the ssame sstory,” said Mirmir, his golden eyes gleaming.

“When did it happen?” demanded the Hanged Man. “When I left him, Dar was not old and worn out. We’re not old! It’s not time for us to die! My children are still infants!” He glared at Mirmir.

The snake coiled his muscular body into a spiral and swayed next to the Hanged Man for answer.

“Damn the circle!” said the Hanged Man. He kicked furiously at Mirmir with his free foot. “Damn the cycle and the wheel, and damn the spiral! I’m tired of turning your stupid wheel! Why me? Why Dar?”

Mirmir uncoiled, paying no attention to the Hanged Man’s ineffectual kicks or anger. “Increasse and Decreasse. The cycle does not stop. Birth and death allow each other. Your mother accepted this.”

“It’s cruel.” The Hanged Man sulked. “I suppose you’ll tell about my death, too, as long as you’re ruining our birthday story. Go ahead. Get it over with. Tell me what I have to look forward to. It’s a good thing you haven’t anything to do with children. You’d give them the horrors with your stories. You’d make a rotten babysitter, Mirmir!”

The snake wheezed with laughter. “Every sstory in itss place. Your rebirth is yet to come, unless you want me to stop?”

The Hanged Man snorted and closed his eyes.

MARY

Days passed. From time to time Baubo and Hecate were absent, gone into the world on their own business, but Minerva, Cassandra and Briar Rose stayed with Mary. The children grew and throve. Winter passed into spring and then, imperceptibly, into summer. Bent over the cloaks, now sewing beads and gems into a swirl of water along a hem of the dark cloak and now embroidering sheaves of grain and poppies on the red one, Mary felt each stitch bring her closer to an ending.

The babies ceased to nurse and her breasts regained their shape, though not their firmness. The skin on her belly and hips tightened, but silver lines stretched from pubis to navel. The children crawled and then toddled about, playing, exploring, fighting, laughing, a constant source of amusement and anxiety. The women talked and laughed, minding the children, fashioning the cloaks, working together. Mary felt silent and faded beside their vitality. Hecate often sat with her, reassuring in her acceptance.

Mary felt a growing detachment. Her whole experience consisted of nurture, shaping herself around life so it could be born and grow. She’d gathered, sown and received seed. She’d prayed and danced and poured herself out in an abundance of passion and love so life might continue. She’d lain on rich earth and opened her body to a lover, a vessel for the cycle to which she’d surrendered herself. Yet increase always moved hand-in-hand with decrease. Seed didn’t grow unless the mature plant fruited and dropped it, dying. Were these children, her beautiful little silver and golden fish, her ultimate and final gift to the world?

Long ago she’d been given a seed pouch. Now and then she took it out and fingered the worn cloth. It wasn’t quite empty. A few seeds remained, yet planting seasons passed and she didn’t scatter them. She let other hands plant the garden. Her spirit felt worn and thin, without the vitality to nurture even a single seed. She’d known joy but it wasn’t with her now. Memories drifted around her like leaves falling from trees in autumn. What would happen to these seeds? She must find a safe place for the seeds.

They were not for the twins. They had no need of seed pouches. These seeds were her responsibility and she must find a way to send them forward with a new Seed-Bearer.

She sat with the others and stitched the cloaks, feeling like an empty room. With every stitch and passage of thread through wool, what had been was leaving. With every bead sewn in place something new approached. She’d given nearly everything she could give, stitching the last of herself into the cloaks. When they were complete, there’d be rest and silence. She longed for no one to need anything from her.

One evening Briar Rose set a last linen-wrapped package on the table. Minerva opened it carefully. As thin layers of linen were removed, they could see a glow. The last folds revealed two large golden feathers.

“The Firebird,” said Mary. She turned one in the light, now orange, now gold, now red, with flashes of blue and green like a dragonfly’s wing. The purple cloak looked like a flowing shadow in Briar Rose’s lap. She’d been embroidering the hem with a pattern of fish picked out with silver and crystal beads. She spread it across her knees, exposing the shoulders of the garment.

“Here,” she said, laying the feather across the back of the left shoulder, ‘as though it dreams of being a wing,’ like the story.”

Minerva, at work on the crimson cloak with tiger’s eye beads and charms, draped it so as to expose the same spot. It too showed no adornment. Hecate nodded in silent satisfaction. Mary handed the feather to Minerva, and she laid it against the crimson wool.

“That’s right,” said Mary. “That’s where their father’s feather lay on his cloak.”

Baubo smiled at Briar Rose. “The final touch. Thank you, my dear.”

CHAPTER 13

One day in late autumn the finished cloaks lay side by side. They seemed to gather light into themselves, one the warm light of sun and the other the cool light of moons and stars.

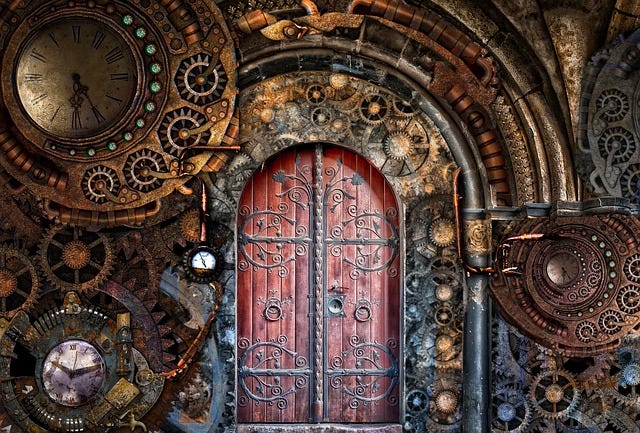

Hecate came that night into Mary’s chamber and quietly packed a few of her belongings. Mary didn’t ask what would happen to her now, but knew the end she’d felt approaching was upon her, and beyond that a door would open. She hoped wherever her journey took her it would be to rest and, filled with that longing, she slept.

In the morning, she bade farewell to her sons. She didn’t weep. They each gave her an affectionate hug and scrambled down out of her lap, eager to be away on their own business. Hecate took up Mary’s bag on a strong arm and they set out into a day of cloud and sun and silver wind. They traveled silently, Mary glad to be moving quietly through landscape that asked nothing of her but to keep putting one foot in front of the other.

They came at last to a weathered house with many chimneys above an ice-bound sea. Dusk drew near and lights shone warmly in windows. A forest flanked the house. Mary felt cold and weary and wanted nothing so much as a hot drink and a warm bed. Hecate rapped on the door, which immediately opened and revealed a tall, vigorous woman with a strong face who might have been any age past fifty. She stood aside and they entered on a gust of icy wind off the sea. Hecate set Mary’s bag down on a floor of red tile. Mary saw a staircase with carved banisters ascending into shadows. The house sounded quiet. She smelled newly-baked bread, lavender polish, fresh linen and burning wood.

Hecate helped her off with her cloak and hood, and as warmth and quiet engulfed her Mary felt such a wave of fatigue it was like losing consciousness. Hecate murmured words of farewell and left before Mary became aware they were parting. The strange woman took her arm firmly and guided her up the stairs.

The woman took Mary down to the end of a long hallway lined with doors. The room struck warm with velvet drapes drawn across windows, but all Mary was really conscious of was the bed, looking soft and deep and smelling of cold sun and pine sap. The woman sat her on a chair like a child and divested her of boots and socks and clothing. She pulled a soft cotton nightdress over Mary’s head, flung back the bedcovers and Mary crept in, feeling the covers laid across her shoulders and a hot water bottle at her feet, and was asleep.

For three days, she hardly left the bed. The woman, who introduced herself as Hel, brought her meals on a tray, made up the fire and tidied the bed if Mary wasn’t in it. She moved quietly and efficiently and didn’t bother Mary with chatter or questions. Now and then Mary heard sounds in the hall, but no one disturbed her. She slept for long stretches in the comfortable, deep bed. No one knew where she was. She didn’t know where she was. No one could find her. No one wanted her. No one needed her. She had no responsibility. On shelves near the windows she found books of the kind she most liked to read. One or two were familiar old friends but many were new to her. As her desire for sleep became satisfied, she lit her bedside lamp, pushed pillows behind her and read for hours at a time, dozing off and on and letting the book slide out of her hands. A comfortable wide chair next to the fire with a hassock for her feet proved a good place to sit and eat or drink a cup of tea. She sat with a cooling cup in her hand, looking into the fire, thinking of nothing, making no plans. Time had stopped altogether. There was no clock in the room. She didn’t know what day it was. Nights were long, dawns frost and silver, the sun low in the sky. Snow fell outside her window.

When she pulled aside the heavy wine-colored velvet curtains, she discovered a landscape of gently undulating white, and in the distance mountains, also blanketed with white. Even when the sun shone the view showed white and pale grey, shadows like smudges. Some way beyond the house stood thick forest, trees standing tall. The snow lay smooth and undisturbed. Gratefully, she surrendered to quiet.

One morning she woke abruptly. It was dark; the fire burned to ash and the room chilly. Her body, warm and cushioned, felt heavy and soft. As she lay, drowsy and quiescent, she felt the first stirring of curiosity about where she was. This comfortable, warm shelter in the winter landscape — where was it? Why was she here? What lay outside her room?

She threw back the cover and put her feet on the cold floor. She lit a lamp and draped a red wool throw around her shoulders. Her hair felt tangled and heavy against the back of her neck. How long had it been since she’d washed with more than a cloth and a bit of warm water? She knelt in front of the fire and rekindled it, making sure small pieces burned well before putting on a larger log. She drew the curtains and cold air pressed in against her. The sky began to lighten into dawn but it was still too dark to tell if the day would be clear or cloudy. Only the first pallid light tinged the horizon.

She stood with her back to the fire, which began to send warmth into the cold room, curling her frozen toes into a deep sheepskin on the floor, and let her gaze wander. To the right of the door stood the bed with a table next to it. On the table lay a couple of books and a lamp. The bed was tumbled and disordered, pillows flattened and the impress of her body a hollow in the feather mattress. At the foot of the bed, against the wall, stood a wardrobe, solid and imposing. She opened it and found the clothes she’d worn — it seemed so long ago — on the journey to this place. They were clean and folded. She put on heavy socks and thought about dressing herself but decided she wanted to wash first. Her comb and brush were there on a shelf but her hair was such a tangle she couldn’t be bothered and left them there. Fastened inside the door of the wardrobe she found a piece of paper that read:

Janus House

Dark December…

Inscrutable Janus stands in fallow Between,

Hearing distant ebb of Fall’s bright breath

And far-off rumors of gathering Spring.

He looks back…

When Earth exhaled into sensitive folds of Sky,

When trees, trembling and hesitant, released concealment,

Uncovered stood, afraid,

Stood knee deep,

Knee deep in yesterday,

But whispered dreams of the future among bare branches.

He looks ahead…

Over what thresholds…?

Into what seeds, brooding at Winter’s breast…?

Oh Janus, God of memory and hope,

God of door, gate, suspended interval,

Key-Keeper,

Only grant me courage to open each door.

Only grant me courage to accept each outcome…

Courage for the next waxing…

And waning.

TIME IS NOT HERE

The poem struck a deep chord in Mary and tears came to her eyes. She’d seen a carving of Janus once over a gate, one face looking left and the other right. She’d forgotten until now. So, she’d come to Janus House in this time between one thing and the next, and Hel ran the house. But where would she go from here? Was her waxing finished and now only waning left? I’m in the suspended interval, she thought with some sadness. She remembered her impression of an enormous house on the night of her arrival with Hecate. Were there others in other rooms like this who were in their own suspended intervals?

“Time is not here,” she read aloud, puzzling. What did it mean, time wasn’t here?

She shut the wardrobe door and sat in the chair by the fire, tucking her feet underneath her and gazing into the flames. Behind her, dawn slowly crept into the room. It was a clear morning.

The risen sun was throwing long shadows across the snow when Hel knocked and came in with a laden tray. She showed no surprise to see Mary up and the fire burning. She set the tray down and Mary saw a golden stack of thin pancakes, butter melting on top. A dish held some dark purple berry in its own runny syrup to spoon onto the cakes.

“Thank you,” said Mary. Hel knelt and added wood to the fire.

“You’re welcome. You begin to feel rested now.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes. And I found my clothes — you washed them for me. Thank you for that, as well. Is there somewhere I can bathe and wash my hair? I’m sorry, I don’t know exactly where I am or who you are and you’ve given me what I most needed …”

Hel stood quietly in front of the fire, smiling faintly. She wasn’t unfriendly, Mary thought, but somehow grim. It seemed a strange attitude for the keeper of a guest house.

“This is Janus House. It’s a place where people come to rest. Time is of no consequence. Those who are ready find us. Whatever they need to heal and rest and renew is given for as long as they need it.”

“It says on the wardrobe door, ‘Time is not here.’”

Hel stooped and reached into a basket of pinecones on the hearth. She lay them in a straight line across the floor. “We think of time as a straight line, like this. It’s a rule, no? Events happen one after another, in their turn. But here,” she swept up the pinecones and dropped them on the floor in a bunch. They bounced and rolled and came to rest where they would. “Time is like this. There’s no line, but circles and patterns overlapping. Janus looks two ways. He sees what has been and what might yet be. He closes the circle but it’s flexible, not rigid. Points on the circle might move together and meet, or intersect with other circles. Time, in the limited sense of a rigid line, isn’t here. Do you see?”

“Yes,” said Mary slowly. “I see.”

“Here at Janus House there’s only now. Your history is a place in your circle that might not yet have happened, or might have happened unimaginable ages ago. Your future may already be here waiting for you, or it may arrive behind you. Here there are no rules and no limits. You’ll eat, sleep, play, laugh, weep and heal as the moment for each thing arrives. There’s only what’s now.

“Are there are other guests?”

“Oh yes. There are always guests.”

“I don’t know where I’ll go from here. I’ve no place to go. I’m alone now.” Mary looked away from the tall, remote figure, ashamed of welling tears. She felt used up.

“You’ll stay until you’re ready for what’s next.”

She wasn’t unkind, but Mary felt humiliated. What a pitiful contrast she made to Hel’s calm, clear presence, her chilling competence! She felt disheveled and unwashed. She’d lost her mate and left her children, and hardly felt capable of leaving her room, let alone considering the future.

“There’s a room downstairs next to the kitchen for bathing. You’ll find it well equipped.” Again, the slight smile. She gave Mary directions to the room and invited her to join other guests at meals downstairs or use the common rooms if she felt inclined. “You may like to go out, as well. It’s cold here but we’ve plenty of warm clothes for you to use.” She glanced out the window. “Don’t go far today. This afternoon there’ll be snow.”

Mary ate her breakfast with appetite, dressed and cautiously opened her door, looking down the quiet, empty hall. Her room lay at the end of the corridor. A window looked out at the same view she enjoyed from her room. A few steps along the hall, on the opposite side from her own, she found another door, and then another and another. She lost count as she followed Hel’s directions, found the huge staircase she remembered from the first night, and descended. The kitchen proved easy to find because of cooking smells and the chatter of women working there.

Mary returned her tray and thanked them, praising the food. One of them took her out of the kitchen and into a hall, opening a door and revealing a large room, as large as her bedroom, with a brightly burning fire, a narrow high table with a padded top, a shelf of thick towels with robes hanging on hooks beneath it, a round table with bottles and jars on it and, most welcome of all, a deep bath filled with steaming water.

“Oh!” exclaimed Mary in delighted surprise. “How beautiful! Thank you!”

The woman smiled and left her and Mary shut the door, shed her clothes, letting them lie where they fell, and moved to the table. There she found what she needed for her hair, smelling of rosemary. She set the shampoo, a cake of soap and a pitcher on a low stool next to the tub and climbed in.

It felt blissful. She rested her head on the tub’s rim and slid down, her hair floating around her. For some reason the touch of the warm water, the embrace of it, made her want to weep. Her body felt lonely. She thought, am I lonely?

I can’t take care of anyone else, she answered herself immediately. But am I lonely for someone to take care of me? She didn’t want to entertain the question. She sank below the surface of the water, wetting her hair.

She heard a knock on the door. Thinking someone brought more hot water, she called out “Come in!”

The door opened but it wasn’t a kitchen woman carrying water. An old woman she’d never seen before stood there, yet she seemed somehow familiar. She had warm hazel eyes, a generous bosom and hips, hair a faded dun color but still quite thick and pinned in a knot. She smiled at Mary with such warmth and affection that again tears were in her throat.

She shut the door behind her, took the things off the stool and sat down with the pitcher on the floor at her feet. She filled her palm with shampoo and began working it into Mary’s honey-colored wet tangle. “I thought you might like some help,” she said in matter-of-fact tones. “My name’s Mary, too, but that’ll be confusing, won’t it? Here at Janus House they mostly call me Mother, anyway.”

Mary could see why. Mother’s hands were strong, gentle and soothing against her scalp. The smell of rosemary, comforting and clean, filled the air. She closed her eyes against the suds sliding down her face.

“Thank you,” she said. “I did want… I did want…”

“Yes. It’s hard to wash one’s own hair when sitting in the bath. I usually slop water all over the floor when I try it!” The older woman laughed. “And your hair is beautiful, my dear. Mine used to be this color when I was younger.”

She was so warm and easy to talk to that Mary dropped her guard at once, not realizing until she did so how isolated and disconnected she’d felt for…how long? The older woman rinsed her hair, worked in a moisturizing crème, and rinsed again. Seeing the signs of childbirth, she asked about the child and Mary told her about the twins and the deep winter night of their birth.

“I left them to come here,” she said and felt a terrible unacknowledged shame rise up within her. “I needed to leave. I felt so tired. I feel as though I’ve nothing left to give anyone, so I left my boys. What a terrible mother I am.” Her voice broke.

“Now, my daughter,” said Mother, passing her a clean cloth to wipe her face and blow her nose. “They’re well cared for. Baubo herself is with them, she who laughs from the belly, looks out of her nipples, and loves children above all others, isn’t that true? And others besides her, yes? And you know those two children of yours have their own place in the world, as do you. Do you forget the turning wheel of increase and decrease? You’re bound to it still, you and your man.”

Mary couldn’t bear to talk of Lugh. “How did you know Baubo was there?” she asked hastily, “I didn’t say so.”

“No. You didn’t. But I’ve heard things. It’s not important. What is important now is you, yourself. You’ve done well, but for the time being you’ve given everything you can. We who nurture life must learn we can’t do so indefinitely. At some point, we run out of love and if we don’t step away, run away, even crawl away and find some path to replenishment and renewal, we die. That too is part of the cycle, but a difficult part, for it means coming to terms with our own needs, and we’d rather be meeting the needs of others!”

Mary, having mopped her face and then rinsed it in the sweet-smelling water, leaned back again. “Yes. I was thinking that when you knocked. That I want someone to take care of me now, I mean. But people did take care of me, during my pregnancy and after. I’m ashamed to want more. It’s ungrateful, isn’t it?”

“No. We all need someone to love and care for us. Come out now. The water’s cooling.”

Mary stood and Mother enfolded her in a capacious bath sheet. Mary sat on a stool in front of the fire, wrapped in the towel, and the old woman stood behind her and patiently combed out her tangled hair.

“Hel said everything I needed was here. But I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I don’t know how to help myself. Yet I know I need help.”

“Yes. Everything you need is right here, right now. Janus House is a place where all is allowed. Whatever you do here will be the right thing. Whatever engages you will be the thing you most need. You don’t need to make a plan or work at anything. Just be. Allow your experience to be. Don’t try at anything.”

“Surrender.”

“Yes, that’s it exactly. Surrender.” As she talked, she lay a sheet that had been warming in front of the fire on the narrow, padded table. “Come here, now.

Mary lay down on her belly, putting her face into a cushioned frame so she looked down at the tiled floor. The old woman gently brushed her hair away from her neck, letting it hang in a scented curtain. Mary smelled lavender and felt strong hands against her back. She closed her eyes. She was touched. She was touched and the touch asked for nothing in return. It seemed to her every pain and strain and overworked muscle in her body was summoned, revealed and comforted. The life her body had been living was uncovered, and as Mother’s fingers worked in her tissue, she remembered stooping to plant seeds under the sun’s warmth, kneeling, bending, saying a blessing over each new beginning. She remembered hauling water, raking, hoeing, weeding, pruning, staking, the feel of earth against bare feet. She remembered the wild, vibrant dance of mating, musk, stretch, passionate pleasure. She remembered sun, starlit nights, rain, and then more sun, sweat between her breasts. She remembered ladder, baskets, shapely weight of fruit in her palm. The old woman’s fingers found the ache between her shoulders that was the memory of the sharp curving scythe and rhythm of bend and swing, bend and swing. Muscles, ligaments and tendons in her hips and pelvic girdle remembered the long weight of the twins and then labor. Her body gave up its story to Mother’s listening hands.

Mary woke. She lay on her back, warmly covered. Her body felt absolutely at peace. The old woman was hanging up towels to dry, tidying the round table, wiping bottles of oil and putting them in their places. Mary lay dreamily, thinking of nothing, listening to the comforting sounds of someone else taking care of things. At last she stirred and stretched.

Mother came to her and helped her sit up, offering her a large glass of water. “Drink this, now, and help your body flush itself out.”

Mary drank. She handed the glass back. “Thank you. That felt marvelous. I don’t think anyone ever touched me with such love.”

“Good! Now, I suggest you go out into the fresh air and take a walk. I’ve found some warm clothes for you. When you come back you can eat again, and drink a pot of tea, and then rest. It’ll snow later, so go now and let the sun see you for a few minutes. There are paths in the woods. You won’t lose your way.

When she opened the door and stepped out into cold sunlight, the air felt like a sluice of icy water in her face. Her old vitality stirred, perhaps not entirely gone after all. She thrust mittened hands into her pockets and settled her chin into the folds of a wool scarf around her neck. Her feet found the path as though they’d always known it. As the path wound, she discovered the landscape rose and fell, revealing slabs of rock iced with snow, mounds of bushes and, unexpectedly, a view down to a sea inlet. She followed the path, feeling like a child, excited to be exploring and free of responsibility. She could see forest ahead, its outer edge consisting of bare-branched trees, and the path took her toward it until she walked among thick evergreens.

Through trees she spied movement — a flash of red. She paused, trying to see more clearly. Someone came toward her, running, laughing! It was a child, a child with honey hair twined about with ivy, running headlong. Without thought Mary knelt and held out her arms and the child flung herself into them.

“You’re here! You’re here! I’ve waited and waited and every day Mother said soon, soon now, but I thought you’d never come! And here you are and oh, what took you so long?”