The Hanged Man: Part 4: Yule

Post #31: In which change approaches ...

(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of The Hanged Man. If you prefer to read Part 4 in its entirety, go here. For the next serial post, go here.)

Molly and Eurydice spent time with Kunik nearly every day. They built fires on the shingle and ate picnics. They explored up and down the limb of the sea. Eurydice dredged out of her memory every folk song and story she could, even showing them some of the folk dances she’d known in her old life, while Kunik played his drum. The voice of the drum underneath his hands seemed to draw music out of Eurydice’s memory.

Kunik proved a quiet young man. He was frequently turning a bit of driftwood or bone over in his hands. Eurydice loved to watch him. Broad and strong looking, his hands were incredibly sensitive and discovered every pit, seam and fissure of the material he explored. Sometimes he rubbed whatever he examined over the thin skin on the underside of his wrist, or across his cheek.

“Why do you do that?” she asked him one day. They were squatting together over the thin line of debris left by the high tide. Kunik had picked up a curving piece of bone, a rib, Eurydice thought. He ran it thoughtfully along the curve of his jaw.

“I’m searching for the shape inside it,” he said.

She looked at him. He smiled but he didn’t meet her eyes.

“Are you teasing me?”

“No. It’s just hard to explain. My carvings start as a piece of wood or bone or stone. But inside them another shape is locked, another possibility, another form and function. I can feel that hidden shape. When it’s clear in my mind I uncover it.”

“Like taking off a skin?” asked Eurydice. Kunik smiled widely. It made his round cheeks push his eyes into slits.

“Exactly like. This bone was once part of a living creature. Now it’s a remnant of that life but it’s still something by itself — a bone. It’s transformed. I can transform it yet again into another new shape. I think this is a polar bear. I make a lot of them, but each is different because each is made out of something different. Let’s see what else there is.”

Their four hands quested in the line of debris and Eurydice thought vaguely how easy it would be to confuse his hands with hers. They possessed the same olive skin and broad shape.

MARY

Mary began to feel restless. She couldn’t guess how long she’d lived at Janus House but it seemed months -- perhaps even more than a year. And yet winter never changed. Her exhaustion had long since been assuaged and her twin sons seemed like a memory from another life. She often thought about Mother and the strange night in the forest during which the old man grew young again in the fire. Where did Mother go? Her heart told her all was well and the old woman left willingly and gladly moved on, but to where? And how had it happened? Did Mother know she was leaving?

She could hardly remember the drained woman she’d been the night Hecate brought her here. She felt immeasurably older and wiser, more patient and peaceful than ever before. Yet she felt impatient with the endless winter and sameness of Janus House. What once seemed a refuge now became tedious and dull. What next? What was happening in the world? Where were her sons? Was there any place, anyone, that needed her now? Before the birth of the twins, she had gathered seeds, planted, nurtured the green earth. Was seed awaiting her hand? Was Spring waiting for her somewhere? But Mary felt in her heart the path forward was not like anything that had come before. Was there someone to love, and someone who waited to love her? She walked in winter woods, sat quietly by the evening fire with Eurydice, listened to Molly’s talk, took her meals, and spent time in her room alone working on a gift for the child.

EURYDICE

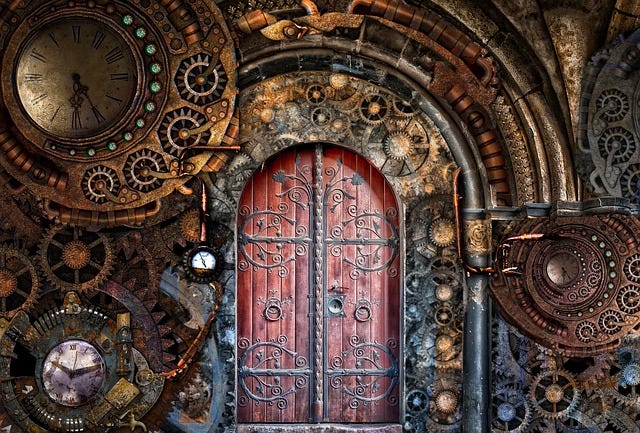

Eurydice spent hours examining the key. It was as long as her finger, the bit decorated with a complicated pattern of wards. The bow of the golden key carried a pattern of scrollwork. Small red gems like rubies were scattered on the bow, shoulders and shaft, as though the key was decorated with a spray of sparks. She’d never seen anything like it before. For some reason, she hadn’t told anyone about it, but she carried it with her and frequently during the day her fingers groped for it, running over the shapes of the jewels on the slim shaft, feeling the delicate scrollwork with a fingernail. What kind of a door did this key open? Was she to search for it? Why else would the key come to her? How exactly did the key come to her? The questions were a kind of mental grit, uncomfortable, irritating.

One evening, as Eurydice and Mary sat together, Eurydice said, “I think I’ve found out something about myself.”

“Are you going to tell me?”

“I want to.”

“I’m listening, my dear.”

“I’ve been thinking about Kunik’s selchie stories and all the skins we might wear — the selves we might be. Remember the door I found in Hades? I dreamt it opened and there was a great crowd of people on the other side. I saw myself in the crowd, over and over, a crowd of Eurydices!”

Mary laughed.

“You were there, too, and…everyone. You were all so happy. I thought it was because the door opened and you thought I did it, but I didn’t. There was a key in the door and that’s what made it open, but I didn’t put it there or touch the door at all. Then a voice in my mind said, ‘Doorkeeper.’

“Did it mean you?”

“I thought so. But maybe it meant someone else. If I was the doorkeeper, I never touched the door at all. It just opened in front of me. The key was there, as though it unlocked the door, but I didn’t do it. I was just…there.”

“Maybe all you need is to be and one of things you are is a doorkeeper.”

“Maybe.” Eurydice looked away. “I’ve been thinking… maybe… maybe I can love enough to allow people to find out what they can be. Maybe love like that is what opens doors. The key is only a symbol.”

“Maybe,” said Mary quietly. She reached out and took Eurydice’s hand in her own. “What a beautiful blessing to bring into the world!”

“Oh!” Eurydice bit her lip. “That sounds like so much to live up to, Mary! I wasn’t thinking of anything that big. I just thought maybe I might help a few people open the way.

“I myself am in need of that. As you’ve confided in me, I’ll tell you I’m restless. I think I’m ready to leave Janus House but I don’t know how — or where. I just know I’m no longer peaceful here. Something calls me, but I can’t quite hear it yet. I don’t want to leave you and Molly, but I think the time is coming when I must.”

“Perhaps it’s something like the selchie feel when they’ve been too long out of their skins. They long for what they’re made of, though it means leaving those they love.”

“You’re wise. That’s comforting. Yes, I think it’s exactly like that. I’ll tell you something else. I think the time approaches when Molly will also choose to leave. I don’t think she herself is aware of it yet, but I foresee it. Have you noticed lately how she’s grown up? She’s happy now, playing with Kunik, but that young man has opened her eyes to life in a new way. I think Molly will soon begin to feel restless too, and wonder what comes next. I’ve been working on a gift, something she might need.”

Mary and Eurydice sat long by the fire that evening, allowing it to burn down to glowing embers. Eurydice went to bed with sadness. She would miss Mary and Molly. She’d noted Molly’s new growth and maturity, as well as Mary’s gradual withdrawal. She too felt change coming to Janus House.

MARY

One day Mary and Molly set out together from Janus House. To Mary’s surprise, the path took them into the woods instead of down to the sea. It was a quiet, steely day. Nothing stirred. Snow like sheets stiff with dirt draggled on the ground and in the hollows. Trees seemed to watch and listen, hostile. The very air felt tense, on edge. Mary felt like an intruder. She sighed. Would winter ever break into spring? A subdued Molly slipped her mittened hand into Mary’s, a thing she did less and less, Mary had noticed. For once her cheerful exuberance was muted.

“Do you want to go back? It’s not a nice day.”

“No,” replied Molly with something like defiance. “There’s nothing there but the fire and a snack and tea, and then dinner, and then nighttime. It’s always the same! And the cold pressing in against the windows!”

Mary stopped in surprise. “I never heard you talk like this before! I thought you loved it here!”

“I do! I did! But it doesn’t change! I’m afraid Kunik will leave soon. Then what will there be to do? How much longer am I going to be here? Is this all there is?” She looked up into Mary’s face, mutinous, on the edge of tears.

“Molly…” Mary began, but forgot what she was saying. Something disturbed the heavy cold and silence of the watchful wood. A thread of sound wound slyly through the sentinel trees. Woman and girl looked into one another’s eyes, listening. The melody mocked, beginning clear and silver and then drifting vaguely away, as though fading, and then present again, closer, though from a different direction. They heard three clear notes, repeated over and over, like a call. The sound stopped. Mary closed her eyes, the better to listen. A sudden scent of damp earth came to her nose. She opened her eyes in surprise and found only the weary winter forest around her. She turned her head, trying to catch the scent again. Cold air scoured the inside of her nose. Again came three notes, demanding, compelling. With a sudden screech and sweep of wings that made them both duck, a white owl took off from a branch over their heads, a single silver feather drifting down into Molly’s hand.

A white owl in the daytime! Mary thought. It can’t be…

Oh, the piping! Let it come again!

Now Mary felt at one with the woods, no longer an intruder but listening… tense and straining. Cold pressed down around her. Molly edged closer to her and they stood, hand in hand, shoulder to shoulder. Something approached.

Three notes and then a single note, a pause, the note again. It sounded, Mary thought, like water dripping. She thought suddenly of the slabs of sea ice down at the inlet. Sea ice was melting, drop by drop, onto the stony shingle. But no, she thought dazedly. Nothing could melt in this cold, and besides, she couldn’t possibly hear such a small sound standing here in the woods! What was she thinking? The dripping sound filled her mind, mesmerizing. Note after note, relentless, dropped away. How many notes would it take to melt away winter? How long would it take to hear each drip?

Suddenly she realized the notes were changing. Drip joined drop and now there were several. One fell into water — she could see it clearly in her mind’s eye, hear the splash it made. One fell onto stones — surely it was sea ice melting? Another fell onto earth, not frozen but soft and muddy, looking like chocolate cake, smelling like a garden in the rain. Faster they dripped, more and more drops joining in until they made a trickle, a rill seeking hollows and making tiny ponds before spilling over and hurrying on. Then, clear and distinct above the sounds of melting and water on the move, came the trill of a bird, liquid and beautiful. Tears fell down Mary’s cheeks. She was pierced with joy so keen it felt like pain. She put her hand protectively to her chest.

The music stopped. Mary opened her eyes and saw ranks of cold tree trunks, tired grey swathes of snow on the ground. It was utterly quiet. The only sound was her own rapid breathing. Her cheeks were wet. Her feet and hands were so cold they were numb. She felt as though she’d stood in a dream for a long, long time. Her breathing slowed. The effort of moving, of speaking, seemed too great to undertake. Janus House was too far to find again. The cold bit too deeply to be thawed in front of a fire. She felt a hundred years old and weary to her bones.

“Mary!”

She turned her head unwillingly towards the girl next to her. Molly laid a hand on her arm. “Are you all right? You look strange.”

“Cold,” said Mary through stiff lips.

“Yes, but you heard the piper—thaw is coming! Spring is coming, Mary!” Her face shone radiant, her hazel eyes soft and shining. “Come, let’s go back and get you warm.”

She tucked her arm through Mary’s and they turned to retrace their steps.

***

That night the sound of dripping water disturbed Mary’s sleep. It started slowly, one drop at a time, and then, like an advancing rain, pittered and pattered over trees, rocks, water down in the cove, on the ground and roof of Janus House. Mary turned over uneasily, frowning in her sleep. Through the gentle sound of dripping water came piping, a thin melody, enchanting, wickedly joyous. Mary found herself outside. Steam rose from the ground and the earth felt wet and damp under her feet. She saw with surprise her feet were bare and realized with greater surprise she wasn’t cold. When she stepped in a depression, mud squirted up between her toes. There was no snow. She walked through thin fog. She followed the sound of piping, feeling young and strong, relishing being barefoot on the ground. Piping and path wound between rocky outcroppings and trees, up and down gentle hills and valleys. On and on she walked, and then she climbed a low rise and broke out of mist into sunlight, a muted, early morning kind of sunlight, but not the low winter sun she’d seen for so long. This sun promised to rise high and warm the earth beneath it. For the first time, she could see some way ahead. Just entering a stand of trees in the valley were two figures. One was slim and wiry, bare chested with brown legs and tawny hair, holding a pipe to his lips. A crimson cloak draped his shoulders. He danced, turning and stepping, bending and sweeping from side to side, piping all the while. He possessed the legs of an animal with hooves. The other figure was female and she too danced, danced like a light-footed girl. Mary could clearly hear the sound of her laughter over the piping. But her head was a faded dun color and her figure was not willowy and slim but matronly, with comfortable hips and ample bosom. It was Mother.

Mary, in her dream, tried to call out but could make no sound. She raised her hand and waved, trying to get Mother’s attention. The piper was already among the trees at the edge of the woods. Mother didn’t see her, so intent was she on her dance, and in a moment, she too was swallowed up among trees.

“Wake!”

Mary woke. Who spoke? She was alone in her room, in her comfortable bed. The heavy curtains were drawn. It felt like early morning. The room was cool with morning chill. Had she herself spoken? The word had sounded like a ringing command.

Mother. Mother with him…the piper. Lugh. She lay still, remembering, half smiling, half weeping. Lugh. Musk and seed. Green fire in the mouth of winter. Feel of damp earth under her feet, sweat slick between her breasts, desire, salty and thick on the back of her tongue. The piper was abroad, calling…

At breakfast Molly was quiet and heavy-eyed. When Mary inquired if she felt well, she said curtly she’d had bad dreams, making it clear she didn’t intend to discuss the matter. After breakfast, she put on her outdoor clothing to go and meet Kunik. Mary cautiously asked if she might come too, and Molly assented.

They set out together, Molly walking ahead with her hands thrust firmly into her pockets. Mary smiled to herself. Evidently it wasn’t a handholding sort of day. The path took them down to the sea and Kunik was there, searching the tide line for treasures, while Eurydice sat on a stone and looked out across the inlet.

Molly went straight to Kunik, squatted down and began to talk in low tones. Mary joined Eurydice, who greeted her with a raised eyebrow and a nod at Molly.

“Bad dreams,” said Mary in explanation.

“Ah. Kunik will help.”

They sat companionably, looking away from the two young people. Kunik began to drum in an intermittent, hesitant fashion, as though learning a new rhythm. The women clambered off the rock and sat behind Molly, near enough to hear but not disturbing the intimacy between boy and girl.

(This post was published with this essay.)