The Tower: Part 5: Imbolc (Entire)

In which you can read without interruption ...

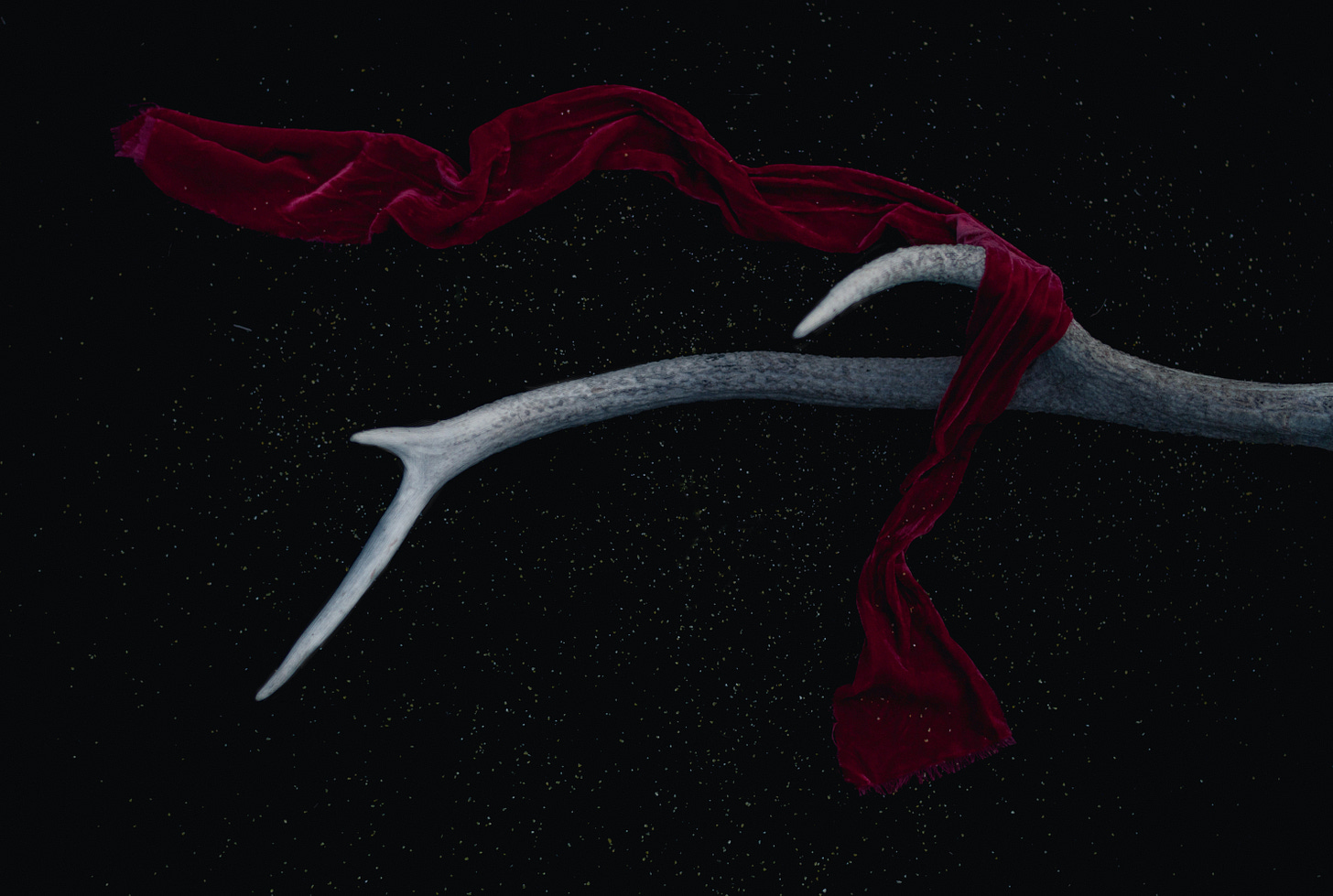

PART 5 IMBOLC

(i-MOLG) February 1; strengthening light, fertility and creativity. Awakening of youthful, chaotic energy. Midway between Yule and spring equinox.

The Card: The Star

Creative potential; renewal; new cycles.

CHAPTER 14

ASH

“Are you sure this a good idea?” Beatrice whispered a few minutes later.

“No,” Ash admitted. He wasn’t sure at all, but his curiosity was irresistible.

The dance, abruptly ended, already seemed like a dream. The dancers and the lynx had melted away into the forest. The candles were snuffed, the bonfire as cold as though it hadn’t burned in years. The ice-glazed forest stilled into a waning winter night.

Baba Yaga had sent everyone away, except Poseidon. He reclaimed his trident and threw a wolfskin cloak around his shoulders as the others left the clearing.

As the dance ended, Ash left his cozy vantage point in the scarf’s folds and flew into the shadow under the eaves overhanging the front of Baba Yaga’s hut. As he perched there, he heard a faint scraping sound, and the window nearest him opened a crack.

“Who’s opening it?” asked Beatrice fearfully.

“It’s the house,” said Ash. He edged down to the window gap and squeezed through.

“Phew!” Beatrice gasped.

They found themselves in Baba Yaga’s bedroom. It was a tiny room, containing nothing recognizable as furniture apart from the bed, which was a frame made from bones. A malevolent-looking skull of no identifiable species glared from the top center of the headboard. The bedding was a malodorous nest of stained and grimy sheets and blankets, the uncovered pillow a sodden, lumpy cushion the color of cold dishwater. The whole room smelled eye-wateringly of old fish, unwashed clothes and imperfectly tanned animal skins. The floor was heaped with tangled, soiled clothing, towels and bedding.

Hastily, Ash flitted through the gaping door. The bedroom consisted of a small square taken out of the larger square of the hut. Ash and Beatrice now found themselves in the single L comprising the rest of the floorplan. Here stood a rickety table with a splintered bench along one side and an old battered chair at the head. A small, obese iron stove squatted in a corner. A tiny galley kitchen contained a stained sink and a counter piled high with dirty dishes, pots and pans. An old-fashioned mangle sulked on the floor against the wall. Next to it leaned a broom with a long tassel of what looked horribly like human hair, clotted with filth

The hut tilted and began lowering.

“Quick! She’s coming!” shrilled Beatrice.

Ash darted among the rafters, which hung with cobwebs that clung greasily to his body. He wedged himself above the junction of three beams and peered down through a slot allowing him to see most of the room. Beatrice crawled out of the fur on his chest and settled herself on the beam over which Ash looked.

The wooden floor below them was littered with bones, dirty utensils, mouse tails, wood chips, cinders, lumps of rotting food, teeth, lurking clumps of grease-coated spiderweb, lint, dead skin, hair and dust balls looking as though they’d been spawned by the Black Rabbit of Inle rather than bunnies.

The front door opened smartly. Baba Yaga and Poseidon stepped in and it slammed behind them.

Ash watched Poseidon take in the room with one swift glance, Baba Yaga a step behind him. Poseidon rolled his eyes, cocked a sardonic eyebrow and turned to her with his crooked grin.

“To what do I owe the pleasure?” he inquired mockingly.

“My pleasure,” she sneered, “not yours. How about a game of Keepsies with old Baba? Show off your pretty balls, sonny! Give an old lady a thrill!”

Holding her gaze, the smile still in place, Poseidon placed his trident tines on the floor and unscrewed the end of the wooden staff. From the opening, he spilled a handful of marbles.

She smiled the most malevolent smile Ash had ever seen on a human visage, and he squirreled away the picture in hopes of imitating it for Mirmir.

“Clear yourself!” she demanded, looking down at the floor. Without waiting to see what would happen, she stumped into her bedroom, rudely slamming the door behind her. In a moment she returned, weighing a wrinkled, brownish skin bag adorned with sparse, curling black hairs in her hand.

“Is that bag made of what I think it is?” Beatrice murmured in Ash’s ear.

“Shhh!” He hissed back.

Obediently, a wide circle on the floor had cleared itself of debris. Baba Yaga and Poseidon stood eyeing each other across the circle, weighing their marbles in their hands.

“Keepsies it is -- if you’re sure,” Poseidon said slyly.

Baba Yaga snorted. A blob of mucous left her nose and, halfway to the cleared floor, made a 90-degree turn and hurtled into a corner piled with debris.

“Shall we honor the season and play Last Clams?” asked Poseidon.

“That’s played in the snow, Numbwits!”

“Too cold for you?” Poseidon needled.

Baba Yaga hissed, clapped sharply, stomped one bare foot, and screeched “Last Clams!” as the cleared circle filled with two inches of slush.

“Why did she say it aloud like that?” Ash whispered to Beatrice.

“Probably claiming some kind of advantage,” said Beatrice. “Everyone says she cheats. Hush!”

“I’ll do the honors, then,” said Poseidon, and he made a shallow hole in the slush with the heel of his supple boot. With his hands, he shaped the hole into a cup, smoothing the slushy edges. Meanwhile, Baba Yaga measured off twelve feet from the hole.

“Shall we say five for an ante?” Poseidon asked.

“Ten!” she fired back. “If you can bear to lose that many,” she added with a sneer.

“Suit yourself,” he said. “I believe I can fit ten more into my trident handle.”

Poseidon knelt on the twelve-foot mark. He lay his trident staff in the slush, making a shallow groove to the slushy cup he’d formed. Laying the trident aside, he shot an opaque marble, ivory tinged slightly with pink, down the trench toward the cup with a powerful flick of his thumb. The marble rolled about three quarters of the way to the cup before bogging down in the slush.

Baba Yaga cackled triumphantly. She loosened the drawstring tie around her bag and peered into it, stirring with a finger, before choosing her marble. She withdrew a red one with a yellow eye and held it up between her thumb and forefinger. Ash smiled appreciatively at her sense of theater.

Poseidon moved aside and the Baba, in her turn, knelt. She leaned forward with her elbows on the floor, the posture revealing scrawny naked buttocks as the hem of her short tunic lifted. Squinting, she lined up her shot, waggling her rump like a cat getting ready to pounce. Ash, taking in every detail, gave his own bottom an experimental waggle.

She made the shot with a grunt. Her marble clicked against Poseidon’s, moving his forward. Evidently, the hit earned her another shot, for she again searched her bag and this time withdrew a white marble swirled with bloody color.

Ash and Beatrice watched, fascinated, as the hag and the sea king made trenches, selected shooters and gloated over each victory. Ash could see the slush made the game impossibly difficult. Snow would have been much easier to play in. As Baba Yaga’s first marble approached the slushy hole, she was unable to propel it up and over the shallow lip. She cursed, danced with rage and spat. She dug new trenches and advanced on the cup from other directions with other shooters, but still was unable to get her first marble into the hole.

Then, suddenly, she was successful. The marble slipped in smoothly as though rolling downhill, the first one in the cup.

Poseidon, who watched every movement his adversary made, cleared his throat meaningfully and glared at her while she crowed with satisfaction.

“Did you see it?” whispered Beatrice.

“No. What happened?”

“The floorboard raised up and tipped it in!”

Poseidon stalked around the circle, examining the several trenches and the marbles in play. Selecting a new shooter, this one black with a pattern of white stripes, he expertly hit one of the Baba’s pieces, earning a second shot. He then gave his attention to the marble closest to the cup. Kneeling, he took aim with one hand while giving two sharp raps on the floor with the knuckles of the other. As he made the shot, the whole hut tilted slightly and the marble rolled sweetly into the cup, just as Baba Yaga’s had done.

“Cheat!” shrieked the Baba.

“You started it,” replied Poseidon calmly.

Baba Yaga stomped to the door, flung it open and shrieked, “Don’t you dare help him! I’ll break your knees! I’ll beat you! I’ll take away your scarves and let you freeze! I’ll make you walk over hot coals!”

“Save your breath,” Poseidon advised. ‘We made an agreement. If needed, the legs would help me, in exchange for a gift.”

“Gift? What gift?” screeched Baba Yaga.

“Something they’ve always wanted. An ankle bracelet.”

“What?” Baba Yaga looked dumbfounded. Poseidon’s face was full of mischief as he grinned at her. Beatrice vibrated with silent laughter.

“An ankle bracelet,” Poseidon repeated clearly. “Honey invariably catches more flies than vinegar, my dear. Shall we continue?”

They played on, Baba Yaga taking every opportunity to cheat undetected with the help of the floor, but unable to evade Poseidon’s watchful eye. Every time she cheated, he rapped what could only be a previously-agreed upon code to the chicken legs, which obediently tilted to assist his shots. One by one, their marbles rolled into the cup.

Cheating aside, Ash thought they were evenly matched. Neither gained a permanent advantage over the other. At the end of the game Baba Yaga possessed two marbles left in play to Poseidon’s one. With an expert shot, he slammed his last one home and won the game.

While the Baba fumed, stamped her feet and muttered invective, Poseidon scooped the marbles from their slushy resting place and examined them on his broad palm.

“Very nice,” he said with approval. “An oxblood, a tiger and a lovely jasper. What’s this called?” he held up the first marble she had shot, red with a yellow eye.

“That’s my devil’s eye. It’s part of a set,” she whined. “One’s no good without the other. Poor old Baba, cheated out of her finest shooter! My prettiest! The joy of my old age! The heart and soul of my collection!”

Poseidon eyed her. “I suppose I could give it back to you,” he said.

“It’s only right! It’s only just! You cheated poor old Baba!”

Poseidon poured all the marbles but the devil’s eye into the hollow staff of his trident and screwed the end back on.

“I’ll make you a deal,” he said.

“A deal? A deal? I don’t make deals with thieves and cheaters!”

“Well, in that case…” He began unscrewing the end of his staff again.

“What deal?” she asked resentfully.

“You know and I know if the Yrtym breaks down entirely Webbd is lost. We must do everything we can to support healthy cycles and seasons. The Rusalka will seek mates among the animals, and tonight Cerunmos was reborn. I propose I join the fertility ritual and add my energy to theirs, allowing the Rusalka to increase their contribution to the next cycle of growth. I’ve already spoken with them, and they consent to my presence, but they’re unwilling to add to the ritual without your agreement.”

“You expect me to sell my girls for a measly marble?” Baba Yaga pretended affront, but Ash saw a calculating gleam in her eye.

“Certainly not. I ask you to honor their consent and my intention in exchange for the prize of your collection. Of course, we could do nothing and let Webbd unravel as it will. I suppose in that case marbles will cease to matter.”

“Give it to me,” Baba Yaga demanded, holding out her hand.

“You agree to the deal?” Poseidon closed his fingers firmly over the devil’s eye.

“I agree!” she screeched. “Hand it over, you pilfering pirate, and get out!”

“Crawl back into my fur,” Ash whispered urgently to Beatrice. As she did so, Poseidon put the marble into Baba Yaga’s palm.

“Begone!” she shrieked, and in a swirl of air the lamps went out, the slush disappeared and the door crashed open. Poseidon, trident in hand, crossed the tilting, lowering floor to the gaping door in a few strides. Outside, the approaching dawn tinged the sky with pale light. Ash launched himself from his hiding place and followed Poseidon out the door, silent as a shadow. Poseidon’s form dropped away below and behind him as he sped away from the clearing and into the forest.

CLARISSA

Morfran, Marceau, Poseidon, Vasilisa and Clarissa gathered in the plunge pool. Many Rusalka were present as well; those whose mating season was not late winter. Sofiya, Morfran’s mate, an owl in her animal aspect, was not there, and neither were the Rusalka who took the aspect of fox and lynx.

Clarissa felt swamped with conflicting emotion. Irritation was uppermost, and she allowed her demeanor to express it, staying on the edge of the group with folded arms and an expressionless face. Nobody paid much attention to her bad mood, which increased her annoyance.

She felt uncomfortably aware, again, of her youth and inexperience. The birch wood positively hummed with sexual power. She felt it and responded to it, but was unable to participate or contribute, aside from the dance. The fact that Marceau and Vasilisa also stayed on the sidelines during the second part of the Imbolc ritual didn’t help the awkwardness of being caught between childhood and adulthood. She was curious, fascinated and a little afraid of the raw energy sizzling and sparking just out beyond sight and hearing. The huge footprint of the lynx in the snow, the feather dropped from an owl and the vixen’s midnight love song burned in her blood and body. Every interaction carried an erotic charge.

She wished passionately for Seren, but a small voice in her heart of hearts whispered the suspicion he would have hated such an elemental show of sexuality. Disloyal, she thought to herself. You don’t know that. He might have joined with the sacred consort and added his energy to the ritual. What’s more fertile than creativity?

She dared not disobey Baba Yaga’s command to accompany the others wherever they were going, in spite of her show of defiance, but she made her reluctance clear. She’d taken no part in the plan or discussion. She thought they were going to see Sedna, whom Marceau had spoken of before they came to the birch wood, but she wasn’t sure even of that.

She coldly ignored the stirring interest and excitement she felt about being in the sea with her own people, seeing new places, trying to discover more about the mysterious Yrtym and collecting stories. It felt gratifying to know when she met Seren again, she would have as much to tell him as he to tell her, but she knew she belonged with him and refused to take pleasure in any delay in rejoining him.

Still, the stories made up for a great deal. Morfran, Marceau, Poseidon and Vasilisa knew many tales, both familiar and new to Clarissa. The Rusalka proved a treasure trove, not only of animal stories but also secret traditions and stories of the rye and poppy fields and the endless birch woods. Clarissa listened, enthralled, to stories about Baba Yaga, sea creatures and people, and tales of the private lives of animals. In exchange, she repeated her father’s tales and poetry and stories she’d learned from Rapunzel and Persephone. She longed to share some of Seren’s tales, but loyally refrained, though she mentioned his enchanting performances whenever she had a chance.

Now, as they left the birch wood for the open sea, Clarissa swam beside Marceau. Morfran and Vasilisa made their farewells and slid into the plunge pool as well. She watched as Poseidon took each Rusalka in his strong arms, looking deeply into her eyes and kissing her warmly on the mouth. The Rusalka smiled at him and returned his caresses with a kind of grateful reverence. Evidently, his role in the fertility ritual had been successful.

She had seen nothing but tracks in the snow of the lynx, Cerunmos, since the dance.

The Rusalka slid into the water after Poseidon. They intended to escort the group to the portal and test its accessibility for themselves.

Clarissa arched forward in a dive, feeling her tail come briefly out of the water as it propelled her down after Marceau. She swam, the others about her, down and then sideways, rising at last toward sunlight filtered by clouds. Her head broke the surface and she found herself in the sea, the others around her. The Rusalka had stayed behind. The portal was open.

Poseidon took the lead. He set a swift pace, and they traveled for a day and a night and another day, the water growing steadily colder as they swam north. They began seeing huge, floating islands of ice, only a small portion of which showed above the surface. These were carved into fantastic ridges, arches, mountains and caves, like frozen clouds fallen into the sea.

Clarissa, gazing around her in wonder, gradually dropped behind the others and was startled to nearly swim into them. They had stopped, floating upright and looking ahead. As she made an abrupt adjustment to her own speed she saw, a yard beyond them, a vertical wall of water, exactly like the one outside the lighthouse. Here, too, the water had receded from the land, holding itself back as though invisibly dammed.

“It’s all right,” she said. “I’ve seen this before. Just swim to the edge and slide down.”

“Wait,” Poseidon commanded.

Clarissa turned in time to see several seals emerge from the water’s gloom. The February sun sank.

The seals approached Poseidon, looking into his face with liquid dark eyes and frisking around him.

“King Poseidon?” said one. “We haven’t seen you in our waters before.”

“Greetings, Seal People,” said Poseidon. “We’ve come in search of Sedna, and to learn how it is with you here in the North’s cold water.”

“We are not Seal People, King,” said the seal. “We are Selchie. As you see, it is not well with us, or with Sedna. She is out there, huddled on the bare sea bed. She’s angry and none dare approach her. Sedna and her people are cut off from the land, and they from us. The land starves for the sea, and we starve for the land.”

“We’ve come to see if we can help,” said Marceau. “Disconnection and breakdown are everywhere. We’re trying to learn how to repair it.”

“Come back to our grotto tonight,” said the selchie. “Night is falling, and the nights here are cold. Sedna has no fire. You’ll freeze. We want to hear your news, and you can rest and eat. It’s better to approach Sedna in daylight.”

“Thank you,” said Poseidon. “We will come with you.”

Clarissa never forgot that night. She missed her father, Irvin, acutely. He would have gloried in the Selchies’ grotto, a cave half filled with water and illuminated by shallow half-moon bowls of burning blubber set in natural stone niches above the water line. Both Selchie and grotto smelled strongly of fish. Selchie and merfolk alike satisfied their hunger with raw fish as they swam to the grotto. Once there, after more complete introductions, the Selchie and half-humans found one another equally fascinating. Morfran, whose grandfather had been a selchie, appeared more animated and eager than Clarissa had ever seen him.

Having established mutually friendly relations, Poseidon and Marceau turned the talk toward Yrtym and the consequences of its breakdown. The selchie listened with interest as Poseidon outlined Yrtym’s ubiquitous role on Webbd.

“It is an invisible net, then, catching and holding all life? The sea as well as the land?”

“Even the stars,” said Marceau. “The constellations are changing. On land, life is dying. Gateways between peoples and places are breaking down. In the sea, volcanic activity heats the water, which disrupts the food web. Before long, people such as yourselves will be impacted.”

“We already are,” said one of the selchie. “Nurseries and breeding grounds disappear as the sea withdraws from the land. The threshold places are empty and barren. Sedna’s anger smolders, and no one knows how to comfort her. The land people cry out for food and the sea’s return so they can hunt on the ice again. Nothing is as it should be.”

Clarissa, worn out after the long swim, found a place against the grotto’s wall to sleep, and drifted away to the selchie’s silvery-sounding voices and the deeper tones of Poseidon and Marceau, rocked in a watery cradle of stone.

The next morning the selchie accompanied them back to the sea’s edge. After a friendly parting, the company from the birch wood swam out of the wall of water and slid down to the bared sea floor, following Clarissa’s example and transitioning into human form as they did so. When Clarissa stood once again on two legs and looked around, she saw a stranger, a man approximately Morfran’s age with large dark eyes and silky black hair brushing his shoulders. A stylized black seal tattoo decorated his left upper arm.

He smiled apologetically at their surprise. “One of the selchie is my mother. I was visiting her when we found you, and I chose not to reveal myself while we talked. My father is human.” He pointed toward the distant land with his chin and gestured at the bare sea bed before them. “This is like a hole in my center.”

“What’s your name?” Vasilisa asked.

“Please call me Pim.” He turned to Poseidon. “Traditionally, the shaman visits Sedna to honor her and ensure good hunting, but when the sea left the land Sedna forsook her people. The shaman can no longer approach her. The places where we hunted seal and walrus are nothing but bitter stone and dried salt. The whales do not come to feed, and the polar bears are dying. Our fishermen must walk a long way, carrying their kayaks, to reach the water, and they cannot launch their boats onto the sea without climbing a rock or an ice slab.

“Then you arrived, talking about Yrtym and trouble elsewhere on Webbd, and I realize what is happening to me and my people is only a small part of a larger change. I am a man with two tribes and two families, belonging wholly to neither. I am not a shaman. I’m a drummer and a storyteller, a bridge between the selchie and the ice people. I want to help both my families. Sedna is our mother. We depend on her. I want to go with you to talk with her.”

“You’re welcome to join us,” said Poseidon. “We don’t know how to live here, or anything about Sedna. Perhaps we can help one another.”

They looked across the barren, rocky plain of salt-encrusted ice and sea debris at a world without color. The dark watery wall behind them emphasized a landscape of grey and white in which sky, the distant land and the bared seabed merged together. A dry wind knifed through Clarissa’s unprotected flesh, making her feel weak and vulnerable. Some way ahead she could see a structure. It reminded her of the shipwreck in which Marceau made his home, but this skeleton looked like bone. It leaned tipsily, like a bleached ship.

“Sedna is there,” said Pim. “Ever since the water receded, she has been there. We don’t know why she doesn’t return to the sea.”

They began walking, bare-footed, across the harsh sea floor. The cold pressed against them like an invisible barrier. The rocks hurt Clarissa’s feet. Morfran, with his twisted hip, struggled to keep his footing, and Marceau took his arm.

Pim fell into step beside Clarissa.

“I’m a storyteller too,” she said.

He glanced sideways at her and smiled. “Are you? Maybe we’ll have time to share some stories. I don’t have my drum with me, but I could show you some of our dances, too.”

“I’d like that,” said Clarissa.

The structure was the tilting skeleton of a whale. As they drew near, the wind brought a stench of rotting fish and flesh. Clarissa clapped a hand over her nose and mouth. “What is that?”

“I believe it’s the skins,” said Marceau, gesturing to several skins flung over the whale’s rib bones. The ivory bones were pitted, broken and cracked, the backbone tapering gradually to the tail. Lying on her side with her knees drawn up, her back against the ridges and knobs of the spine, lay a slight figure cloaked in snarled black hair.

Clarissa saw no evidence of fire. Gnawed bones were scattered around the whale skeleton, but none looked fresh. One of the skins was that of a polar bear, the fur yellowed and thin, and Clarissa could see strips of tattered flesh still adhered to it. There were also a couple of sealskins, the fur looking soft and thick but smelling powerful enough to make her eyes water. She wondered how Sedna, if this woebegone figure was Sedna, could stand it.

The curled-up figure remained motionless and Poseidon and Marceau stood looking down at it uncertainly. Surprisingly, Morfran awkwardly lowered himself onto one knee on the hard stones.

“Lady? Sedna? We’ve come to speak with you.”

Slowly, the child-like figure stirred, uncurling. The head turned and Clarissa saw a face decorated with tattoos, a graceful V from hairline to the bridge of her nose and vertical double lines running from lower lip to below her chin. Her dark eyes burned like embers. She tensed and hissed, baring her teeth like a cornered animal. In an explosive movement that made Clarissa take a hasty step back, the woman twisted into an upright position on her knees.

Clarissa gasped.

The woman was handless. Each arm ended at the wrist in a healed stump.

Sedna shot her a fiery look of pride and bitterness and Clarissa felt her cold cheeks color with shame.

Morfran, who remained on one knee, bringing him eye to eye with the starveling figure, said, “We mean no harm. We only came to talk with you.”

“I have nothing to give you,” Sedna snarled.

“We come to give, not to take,” said Morfran.

Eyes blazing, Sedna looked them over. A ridge of muscle stood out in her thin cheek.

“Lady,” Poseidon said when she caught his eye. He inclined his head respectfully.

“I am Marceau, a sea king,” Marceau introduced himself. “Vasilisa, my daughter, who is half human, and Morfran, my grandson, who is half selchie.”

“You are one of my people,” Sedna said to Pim in a harsh voice.

“Yes, Lady,” he replied. “I am called Pim. My mother is a selchie and my father a human. This is Clarissa.”

“You are not a shaman. Why have you come?”

Pim hesitated. Clarissa thought it the question was dangerous. Sedna radiated anger mixed with despair. Perhaps following Morfran’s lead, Pim said, “I’ve come to see if I may serve you.”

Sedna examined their faces in silence. Clarissa felt frozen, her skin plucked into gooseflesh.

“You have nothing I need,” Sedna said at last, and made as though to turn her back on them and lie down again. “Go away.”

“Are you hungry, Lady?” asked Morfran. “May we hunt for you?”

Sedna sat straight again. “You wish to feed me?”

“We would be honored,” said Marceau, with a glance at Pim, who nodded slightly.

“Very well,” said Sedna, and she sat where she was, her dark hair draping her shoulders, as they organized themselves.

After a muttered conference, they decided Pim would go back to his village for furs and clothing. Morfran, Marceau and Poseidon would seek out the selchie and attempt to find a walrus, which would be large enough to feed them all. Vasilisa and Clarissa, to Clarissa’s consternation, would stay with Sedna.

“Offer to comb her hair,” Pim said in a low voice.

“With what?” Vasilisa asked.

“She has a comb.”

The hunters trudged away to the water, looking cold and puny against the back drop of low sun, the strangely arrested wall of water and the desolate sea floor. Pim walked in the other direction, toward land. Vasilisa and Clarissa looked at one another.

Vasilisa approached Sedna and sat, tucking her legs comfortably in imitation, and Clarissa dropped down next to her.

“Your hair is beautiful,” said Vasilisa. “It must be hard to take care of.”

Without hands, thought Clarissa, imagining trying live with such a pitiful loss.

“May I comb it for you?” Vasilisa asked.

Sedna regarded her.

“I have nothing to give you, so don’t waste your time.”

“I want nothing from you,” said Vasilisa, meeting Sedna’s smoldering gaze. “It would give me pleasure to comb your hair. I like cutting and combing hair.”

“There’s a comb somewhere,” said Sedna ungraciously.

Clarissa began searching the campsite and found the carved ivory comb lying within the whale’s ribcage. It was a beautiful object, and she handed it to Vasilisa, wondering who had made it and why it belonged to a woman with no hands.

Vasilisa moved closer to Sedna and asked her to sit sideways to the whale’s backbone so Vasilisa could work with her hair. As Sedna acquiesced, Clarissa felt emboldened to ask, “Are you cold?”

“I am not as cold as you are,” said Sedna, “but you may throw a sealskin around my shoulders.”

Trying not to gag at the idea of the putrid skin wrapped around her bare body, Clarissa draped a sealskin carefully around Sedna, stepping back hastily to distance herself from the smell.

Vasilisa, rather pinched about the nostrils, gathered Sedna’s hair in one hand at the nape of her neck and let it spill over the sealskin. Taking a firm handful of hair near the ends, she began combing through the tangled, salt-stiffened locks.

Clarissa watched the dark fire die out of Sedna’s eyes, leaving only dull apathy, as Vasilisa combed. She looked down at the stumps resting in her lap. The skin on her arms was dry and peeling. Sedna’s lips were cracked and her hair remained lifeless and dingy in spite of Vasilisa’s ministrations. The rancid fur hid her torso, but Clarissa had seen the washboard of her ribs and her shriveled breasts. She hoped the hunters returned soon with food.

The skins draped over the whale ribs shielded Sedna’s spot from the worst of the wind. Clarissa resigned herself to the stench and sat close beside Vasilisa and Sedna, wrapping her arms around her body for warmth.

“This reminds me of meeting another friend of mine,” said Vasilisa casually. “Her name is Rose Red. Her hair is black, too, but shorter and curly.”

Sedna, eyes closed, made no reply.

“Tell us the story,” said Clarissa, exchanging a glance with Vasilisa.

Vasilisa, in a low, soothing voice, told the story of Rose Red and her girlhood in her father’s castle with her mother, Queen Snow White. She described their first meeting in a forest clearing, where she’d found Rose Red sobbing. She remembered the Dwarves in their stone cottage, who befriended Rose Red, and Jenny, another friend. Section by section, she combed Sedna’s hair, smoothing it, running her fingers through it, and passing her palms over Sedna’s shoulders, head and back with firm strokes. Gradually, Sedna’s rigid pose melted. She collapsed inward, looking more childlike than ever, and Clarissa wondered how anyone could fear such a lonely, pitiful figure.

“I’d like to meet Rose Red,” Clarissa said as Vasilisa’s story ended.

“If you go to Rowan Tree, you will,” said Vasilisa.

Clarissa realized she’d forgotten about Rowan Tree and Seren for nearly a whole day. “Do you think she’d mind if I told her story?”

“I don’t think so,” said Vasilisa, “but you can ask her yourself. “Clarissa collects stories,” she said to Sedna.

“Do you know any stories, Sedna?” Clarissa asked.

Sedna shook her head and rubbed her right stump over her eyes.

“Pim said he knew some. Maybe he’ll tell them to us when he gets back. I’d like to know more about this place. I’ve never been anywhere like it.”

“In a land where snow drifts like fallen stars and night sky ripples with color,” Sedna muttered.

Vasilisa and Clarissa exchanged looks.

“That’s beautiful,” said Clarissa. “Do you mean this land?”

“It’s how they used to begin stories,” said Sedna, “when I was a child.”

“Do you remember a children’s story, then?” Clarissa coaxed.

Vasilisa smoothed a section of hair from scalp to ends, and began combing it in long, slow, sensuous strokes.

Sedna did not reply. Clarissa opened her mouth to cajole further, but Vasilisa, catching her eye, shook her head.

They sat silently. Clarissa fidgeted on the hard stones, remembering again how cold and uncomfortable she felt and wishing the others would return.

Then Sedna began speaking, her voice harsh and cracked, as though she hadn’t used it in a long time. Her words were hesitant at first, as she groped for meaning and syntax.

“In a land where snow drifts like fallen stars and night sky ripples with color, there lived a girl, the most beautiful girl in the village. Her mother was dead, and her father a hunter and fisherman.

When it was time for her to marry, men came to court her, but she was proud and refused them all. She wanted…something else. Something more, though she knew no name for what she sought. Her father was angry with her. Her repeated rejections caused bad feeling in the village. It was her duty to marry and bear children, as a young, unattached, beautiful woman was bound to cause problems. People began saying she was proud and haughty and her father could not control her.

One day, walking alone on the ice, the girl found gigantic wolf tracks. She followed the tracks a long way, but never saw the creature who made them.

It was the season of Yr’s return, and the girl walked alone every day, enjoying his warmth and light. She often saw the wolf tracks going inland from open sea among the floating ice.

One clear day she came over a hill and saw movement ahead. A large white wolf trotted toward the horizon, the low sun making its long shadow run beside it. The girl understood then why it had taken her so long to find the wolf. Unless it moved, it remained invisible against the snow and ice and white sky.

Her tracks began mingling with the wolf’s tracks, until she realized even as she followed it, it followed her. She began looking over her shoulder as often as she scanned the horizon ahead, not afraid, but filled with excitement and anticipation. She wanted to see the wolf up close, perhaps even speak to it. Sometimes she dropped to her hands and knees and sniffed fresh footprints, trying to catch a trace of the wolf’s warm scent in the world of empty cold wind and ice.

Every day the villagers shunned her a little more. She didn’t care. Her father, too, suffered, and took out his humiliation on her, but she paid no attention. She refused to see suitors. She thought only about the elusive white wolf. She called him Akhlut.

One spring day she jumped off an ice shelf and found him standing on the other side, as though waiting for her. The girl stood still and they regarded each other across the ice and snow. She judged the wolf to be at least eight feet long and nearly twice her weight. Its white coat looked thick enough to swallow her hand up to the wrist. It watched her out of grey eyes, then turned and trotted away.

After that, she saw it every time she went out, but seeing it no longer satisfied her.

She wanted to touch it.”

Clarissa was so engrossed by the story of the beautiful girl and the wolf she didn’t hear Pim return. She jumped and gasped when he draped a skin around her naked shoulders, and Sedna fell silent at once, the spell broken.

Vasilisa shot Pim an annoyed look.

“I’m sorry,” he said, contrite. “I didn’t want to interrupt you, Lady, but these two are unused to our cold. Perhaps you’ll honor us later with the rest of your story?”

Sedna nodded her head slightly without looking up.

Gratefully, Clarissa clothed herself in tanned hides, skins and fur-lined boots. She took the comb and continued working on Sedna’s hair so Vasilisa could dress as well. After asking for and receiving permission, Pim took the stinking fur from Sedna and replaced it with another, well-tanned and sweet.

While Clarissa combed, Pim and Vasilisa took the malodorous skins away from camp and laid them on a convenient rock. They gathered up the half-gnawed bones and flung them as far away as they could for scavengers. Clarissa watched as Pim unpacked a bale of clothing and furs, a shallow half-moon bowl, two long, sharp knives in hide sheaths and a piece of hide stretched over a hoop about four feet in diameter, along with a thick wooden peg.

Clarissa heard a shout and saw Morfran, Poseidon and Marceau returning, heavily laden. Pim and Vasilisa helped them haul their burden closer to camp, where they laid it down and Pim began butchering, pointing and instructing as he worked. Marceau picked up the second knife and assisted.

By the time Clarissa had finished combing out Sedna’s hair, everyone was appropriately dressed and several pounds of walrus meat and blubber were cut into long strips, ready for eating.

Pim squatted on the ground near Clarissa and Sedna with the shallow bowl, which he filled with walrus blubber. He set three squares of ice around the bowl as a shield from the wind. He showed Vasilisa and Clarissa how to pound the blubber with an ivory tool, and then pulled pinches of what he called “arctic cotton” from a hide bag, soaking them in the fat and tucking them carefully along the dish’s rim. He lit the cotton with a spark from his flint, and fire outlined the bowl’s edge.

“This is a qulliq,” he said. “My people have used them for hundreds of years. With a snow house, called an igloo, and a qulliq, we can cook, drink, dry our clothes, warm ourselves and provide light.”

Clarissa watched, fascinated, as he made a tripod over the qulliq and hung a battered pot filled with chunks of snow over it.

Morfran approached Sedna, who sat watching the activity around her with more interest than she’d yet shown. Clarissa liked to watch him move, with his odd blend of grace and awkwardness. He sat down, positioning himself slightly to the side so he could speak to her face-to-face without blocking her view of the camp.

“Where I come from, we use wolf skins. I’ve learned a bit about tanning their skins. May I take your skins and finish cleaning them? Pim said he would teach me how your people do it.”

Clarissa felt pleased to see Sedna actually make eye contact with Morfran for a few seconds before looking away. She nodded.

“Thank you,” said Morfran.

Marceau and Poseidon draped raw strips of meat and blubber over the whale’s bleached bones near the qulliq. Vasilisa looked after the qulliq, learning the knack of maintaining a steady smokeless flame. When the snow in the pot had melted, she called Pim and Morfran, who were carefully scraping the putrid skins with Pim’s knives.

As they gathered to eat, the short day waned. They sat around the qulliq, even this flicker of fire in the immense cold wastes as attractive as one of Baba Yaga’s bonfires. Pim positioned the qulliq close to Sedna. She demonstrated no desire to move, so the others formed a loose circle, including her, with the qulliq in the center.

Well accustomed to eating raw fish and meat, they chewed lustily on the strips of walrus and even more welcome blubber. Clarissa knew eating the fat was as important as the protein in the meat, as it provided both energy and warmth.

She noticed neither Pim nor Morfran ate at once. Pim produced a carved bone cup, filled it with melted snow water from the kettle, and held it to Sedna’s lips so she could drink. She drank cup after cup. The others shared a wooden cup, but Clarissa took only a mouthful, as did the others, before passing it on. They would clearly need to melt more snow. Clarissa wondered how long it had been since Sedna had the simple luxury of a drink of water. No wonder her lips cracked and her skin peeled.

When the pot was empty, Marceau took it and walked away into the dimming afternoon in search of ice or snow to refill it.

Morfran chose a strip of blubber and offered it to Sedna. Clarissa watched her eyes go from the fat to Morfran’s face, as though gauging the risk of accepting it. He held it patiently, a friendly smile with no hint of pity on his face, and when Sedna leaned forward and took a bite Clarissa felt like cheering. She turned her eyes away, took a grateful bite of her own portion of meat and entered into the casual conversation of the others.

Marceau returned, rehung the kettle over the qulliq, which Vasilisa continued tending as she ate, and they applied themselves to filling their bellies while Morfran murmured to Sedna and fed her strip after strip of blubber and meat.

By the time the second pot of snow had melted, Clarissa and most of the others were replete. Pim, who had apparently eaten his fill, once again held the cup for Sedna, but this time she drained only four cups before turning away. She accepted another strip of meat from Morfran and then one last strip of blubber.

Clarissa and the others drank their fill, and Marceau once again took the pot to refill it. Morfran sat beside Vasilisa and applied himself to his own meal while Sedna sat against her bony support, wrapped in a thick fur that hid her mutilated arms, her black hair a neat curtain around her.

When Marceau had returned and the pot once again held melting snow, Clarissa said to Pim, “Will you tell us a story?”

Pim turned to Morfran. “You are a selchie?”

“Yes,” he replied. My grandfather -- my other grandfather -- ” with a smile at Marceau, “was a selchie.”

“Do you know any of our stories?”

“Only my grandfather’s story”

“I will tell you a selchie story, then.”

“In a land where snow drifts like fallen stars and night sky ripples with color, there lived a young hunter called Tek. His skin boat was the lightest and strongest, his eye the keenest and his harpoon never missed. When his people needed food, Tek pulled his boat onto the sea ice with the other hunters, making camp where the dark water lapped against the ice, or where the seals made blow holes and came up to breathe.

Then he sat or knelt, motionless in his furs, for hours at a time. The people said he left his body, as the shamans did, and his spirit slid into the water, searching for an animal ready to give up its life. He swam among the whales in their season, among the seals and walrus, and darted among the silver fish, fat and heavy with rich flesh, until an animal offered itself freely and followed him back to where his body waited with the other hunters.

After a kill, Tek and his people lifted their faces to the sky, opened their arms and gave thanks to the animal for its life. Tek and his people honored every gift the animal gave: meat, fat, skin, blood and bones.

The young hunter was popular because of his skill, and many women wanted to share his igloo and qulliq, but he favored none of them.

The truth was he felt most comfortable in the world hidden beneath the sea ice, the cold, dim world of shining scale, sleek fur over a solid covering of fat, and the majestic blowing of the whales. The voices of the ice, groaning and creaking, followed him into his dreams. The sea beneath his skin boat held him and rocked him like a mother.

The animals came to recognize Tek’s spirit and welcomed the naked swimmer who visited them with his straight black hair and harpoon.

A group of selchie heard about Tek, and one day his spirit encountered this group. One among them, Selena, found Tek particularly fascinating. His skin was bare and smooth. Dark hair grew sparsely on his chin and upper lip and floated around his head as he swam. He had a layer of fat under his skin, as all healthy animals did.

Selena was young and vital, not yet ready to give up her life for the sake of others, but she noted Tek’s patience as he sought an animal who wanted to follow him into the world above, the world of humans and ice bears, birds and the life-giving air and sun.

He visited her people beneath. Why should she not visit his above?

The other selchie tried to dissuade her. They told her stories about humans who stole selchie skins, imprisoning them for years. They warned her of the anguish of leaving children in the world above to return home beneath, of being torn between one’s life and one’s loved ones.

‘Humans are not like us,’ they said. ‘Their love is selfish. What they call love is only possession.’

‘He is different,’ Selena protested. ‘I know he is different. He comes to our world beneath, and he is not selfish. He takes only those who offer themselves.’

‘If you follow him above as a seal, he and the other hunters will kill you for food.’

Selena began watching Tek and the other hunters from above the water. She avoided the blow holes the other seals used and concealed herself behind rocks or ridges and sea ice slabs. At night, the hunters disappeared into two round snow shelters, lit from within by a dim warm light. After a time, the light went out and remained so for several hours.

On a night of silver moon, Selena clambered out of the water onto the ice. Carefully, she anchored her skin with a stone so the wind could not steal it. She wriggled through an opening in one of the snow shelters on her hands and knees, crawling until the space opened. Three shapes lay under piled furs. The first man snored mightily, and he smelled of some kind of unfamiliar meat. The smell of it was strong in the shelter. The second man smelled of rancid fat and sweat. The third lay on his side, facing away from her. He smelled cleanly of the salt sea, and she knew this must be Tek.

Cautiously, she wormed her way under the furs, bending her knees and molding her body around his. The luscious fullness of her breasts and belly pressed against his hard back and she laid her round cheek against the blade of his shoulder, inhaling his body’s private scent. The mingling of warm breath in the frozen, dark shelter created an icy humidity that chilled every exposed inch of skin. She snuggled closely against the sleeping man, covering her face and ear with her black hair, tucking her shoulder down and pulling in her bottom.

Tek stirred and turned. Selena felt awareness wake in him. Warningly, she laid a finger on his lips, then replaced the finger with her mouth.

His breath, like hers, was scented with fish. His hand came up, rested briefly on her ribcage, and then moved in exploration over the landscape of her human form. It excited her and she stirred against him, torn between the necessity to stay under the furs and the desire to stretch and display herself for his touch.

As she returned his caresses, moving her hand over his muscled shoulders and chest, the slight indentation of his waist and the solid strength of his hip, his warm breath gusted against her cheek, her chin, and her lips, which he possessed again and again with gentle but increasing violence.

Her hand encountered soft, warm, rounded shapes with sparse hair at the core of him, and suddenly she found a hard rod, pulsing, velvet-sheathed, and he gasped when she wrapped her fingers around it.

Selena threw her right leg over him and knelt above him so they felt one another’s breath and her breasts made a cushion between them. She reached down and guided him into the wet divide between her legs, sinking slowly down until her full weight rested on him, though her elbows still supported her on either side of his shoulders.

He bucked under her, swelling and hardening, and she smiled against his lips, pushing into his mouth with her tongue. His hands came around her hips and he pulled her hard against him, thrusting deeply. She made a small sound of delight, and now felt his lips smile against hers. She lifted her hips slowly, feeling the delicious friction as he slid out of her, and then drove them down again with her soft weight.

Silently, they rocked together. Selena could see nothing but faint moonglow. Her senses were reduced entirely to her nipples, her mouth and face, and the place where their bodies joined.

His shuddering release fueled her own, and she writhed and jerked like a fish on a line while it swept through her. She slid off him in a rush of warm fluid and he put out his right arm and gathered her against him, stroking her hair, his breathing quieting. She laid her right hand on his chest and felt his heart’s strong beating.

She slept.

Hours later, when the short day dawned, Tek found one of his sleeping skins discarded near a large rock at the ice’s edge. He picked it up and the scent of their lovemaking came to his nostrils. He returned the skin to the igloo and spent the scant hours of daylight hunched over a blow hole in the ice, his body singing with remembered warmth and softness, his mouth tender with her scent and taste, his heart as loosened and melted as fat in a burning qulliq.

So the selchie Selena and the young hunter Tek became secret lovers. Above the ice, the long nights held them, wordless, naked and passionate. Beneath, Tek sought her out in spirit form, and they swam and played while the sea ice glowed and shimmered around them.

Selena was right. Tek never sought to steal her skin. She was free to come and go as she would. She, in her turn, did not compel him. When he and the hunters had food, they returned to their village; too far from the sea ice for her to visit at night. In this way, seasons passed during which they lived separate lives beneath and above for days or weeks at a time.

During a joyous reunion after some weeks apart, Selena told Tek she was pregnant with his child, and awe and joy filled him.

The other selchie watched Selena and her lover cautiously, accepting her right to do as she wished but fearing a painful and perhaps dangerous outcome.

Tek’s people had no inkling of his secret, but noted he was more remote than ever before, and less interested in the hopeful young women who tried to catch his attention. His prowess as a hunter increased with time; none other could compete with him. If Tek went to the sea ice, he always returned with food for the village.

Inevitably, the other hunters began to envy Tek’s success. That the young man should consistently bring home more meat than more experienced, older hunters and his own peers caused envy, and the other hunters muttered of uncanny powers assisting Tek. Their pride in his ability to send his spirit beneath the ice to hunt turned to distrust and fear. Perhaps he had struck a bargain with Sedna herself, they said, a bargain that might bring ruin and disaster to the people.

It's a strange thing, but people who need not work hard every day to survive soon fall into dissension and dissatisfaction. Tek’s village, with an abundant and ongoing supply of food, grew argumentative and restive. Fights and gossip escalated. Rumor spread. It was no longer necessary for the hunters to work together, and the pride of a shared kill diminished.

Camped on the edge of the sea ice, the other hunters began sabotaging Tek. They blunted his harpoon against a stone when he wasn’t looking. They interrupted his spirit trances by stumbling over him, bringing him back into his crouched body with an unpleasant jolt. They watched him jealously, their eyes unfriendly. Selena and Tek began to feel nervous and the tension in the rounded snow shelters disturbed their delight in their long nights together.

Selena’s time grew near. Seals must give birth on land, and Tek was determined to find a way to be with her and protect her and the child during the vulnerability of birth. As the birth approached, Tek took care to be less successful hunting; choosing smaller animals to assure he would need to return to the hunting grounds sooner. Once there, he would simply wait until the birth was safely over before accepting an animal that presented itself. The other hunters would follow his lead, he knew.

He did not know the hunters had seen him more than once with a certain seal, easily identifiable by a pattern of grey spots. Their vague suspicions and resentments flowered into certainty. The seal was a powerful spirit, perhaps an evil spirit giving Tek an unfair, uncanny advantage. Tek’s pride and arrogance must be smashed to teach him humility.

They decided to teach him a lesson.

The other hunters arranged among themselves that one of them always kept his eye on the young hunter. So it was, when he stole away from camp one day, saying he wished to crouch by a distant blowhole the seals used, they followed him, keeping well out of sight.

Tek helped Selena up through the blow hole and onto the ice. She lay, straining and heaving as she gave birth. The seal pup slid out in a gush of fluid tinged with blood. The little white creature flopped, bursting the amniotic sac, and as Selena turned awkwardly to sniff it, the thick ribbon-like cord attaching mother and child broke.

Tek, weeping and smiling, passed his hands over the pup while Selena nuzzled and spoke to it. Tek did not see the hunter with a raised club until the club crashed down onto Selena’s head.

Tek heard a sickening crunch, a sound that haunted him for the rest of his life. Two hunters restrained him while another took out his knife and skinned Selena deftly, removing the valuable blubber layer under the skin as well. The ice bloomed with Selena’s blood. The pup lay, defenseless and weak, as they butchered his mother, and Tek raged, beside himself with grief.

When it was over the hunters backed away with their bloody prizes. One held Tek’s harpoon and his knife. He fell on his knees beside Selena’s body, pouring out his grief. The hunters left him there, moving away with nervous looks over their shoulders in case the uncanny seal came suddenly back to life and pursued them.

As Tek wept, he heard an expelled breath and a seal poked its head up from a blow hole, nostrils closing and dilating. The seal gave a long, low cry and its lustrous dark eyes welled with tears. Tek rose like an old man and lifted the white pup in his arms. For a moment he held it closely while it squirmed and wiggled, and then he tipped it gently into the blow hole with the seal.

‘Take care of our son,’ he said, ‘please.’

Alone again with Selena’s body, he grieved for a long time. When the short arctic dusk fell, he wiped his face on his sleeve and made his way back to the igloos, leaving the pathetic skinned seal behind for whatever scavengers might come. It was the natural way of things, and Selena, he knew, wouldn’t mind.

The igloo he shared with two others remained empty, and he understood the other hunters meant to cast him out and had gathered together in the second igloo. He was glad. He neither ate nor lit his qulliq, but wrapped himself in his sleeping skins, wishing to never think, feel or remember again, and slept.”

Clarissa wept. In spite of the ending of the doomed love affair, something in her longed for the passion the lovers had shared. It was right, this power and delight in body and spirit. It was lovely, the selchie woman and the man in their snow shelter in the moon-washed arctic night.

“What happened to the child?” she asked Pim. “Did he become a selchie, too?”

“He did,” said Pim. The qulliq cast strange shadows on his face. Wind scoured the bare sea bed, and they hunched and huddled around the flickering light. “Another selchie with a new pup became his milk mother, and he grew up in the sea. When he became a young adult, the selchie told him about his origins, and he ventured onto the sea ice one day and discovered his human form.”

“It was you,” said Morfran. “It’s your story.”

Pim smiled. “Yes. Now I live mostly above, with my father’s people. I’ve told them I’m an orphan from another place. My father is dead now, but I’m a useful hunter and the village accepted me, though they sense I’m different.” He addressed Sedna’s slight, dark figure. “That’s why I’ve come to seek you, Ice Mother. We are your children, the creatures of above as well as the creatures below. Because of you, men possess food and light and life. Because of you, the sea is rich with salmon, seal, whale and walrus. Without you, we will die.”

Clarissa noticed Pim refrained from intimating Sedna needed help, as well. Perhaps she could survive on her own, even without hands, but she didn’t appear to be much interested in survival at this point.

Sedna neither stirred nor spoke in response. After Poseidon and Marceau lashed the skins they’d found in camp, still stinking, but considerably cleaner, to the whale bones to provide some shelter from the wind, they blew out the qulliq and lay down together to sleep in the empty place where land and water once mingled.

CHAPTER 15

The next morning, Pim once again set out for his village, promising to bring back a hide tent for better shelter. Marceau, Poseidon and Morfran returned to the sea, this time in search of salmon. Clarissa and Vasilisa stayed with Sedna, melting snow water and trying to discover some way to connect with the remote, angry, handless woman.

Pim addressed her as ‘Lady’ or ‘Ice Mother’, but Clarissa couldn’t view Sedna as a goddess. Aside from smoldering anger, she appeared powerless, as well as terribly alone. Her spirit seemed to mirror her mutilated body. Clarissa thought she would have been content to lie naked against the whale’s backbone and die rather than seek food, company and shelter, either on land or in the sea.

Yet she accepted both food and water, as well as Vasilisa’s attention to her hair. She ate like one who intended to live. She no longer asked them to leave, watched and listened to all that went on, though rarely contributed. If she possessed power, she didn’t use it to help herself or drive them away.

There was plenty of blubber, so they lit the qulliq and continued melting snow and ice for water. Vasilisa, pinching the arctic cotton carefully along the shallow bowl’s rim to encourage an even, smokeless flame, said to Sedna, “I think this fat would help your hair and skin. The cold and wind suck away our moisture. May I comb some through your hair?”

Sedna nodded without speaking. Vasilisa rubbed a blob of half-melted fat between her palms and rubbed her hands through Sedna’s hair from scalp to ends. She picked up the carved ivory comb and began using it. Clarissa copied her gesture of melting a pinch of fat between her warm palms and knelt before Sedna. She took one of her forearms gently in her hands and began rubbing the fat into her skin.

It was strange to see arms without hands. Her eyes couldn’t get used to the wrongness of it. The stumps had healed cleanly and looked pathetic rather than grotesque. Sedna’s skin was chapped, peeling and flaking, but her arm felt warm and living, reassuringly normal. Clarissa smoothed the fat into it, rubbing gently, and watched Sedna’s skin drink it in. Sedna kept her eyes lowered, looking down into her lap, but she let Clarissa handle her arms docilely. Her passive acquiescence emboldened Clarissa, and she lifted Sedna’s chin with one hand and applied a fingertip coated with fat to her lips with the other. Sedna’s eyes were the deep green of cold water and made Clarissa think of seals and selchie in the strangely-lit world beneath the ice.

“Will you tell us the rest of the story you began yesterday?” she asked.

She removed her hand from Sedna’s chin, and once again her gaze lowered and she hooded her eyes. Clarissa made sure Sedna’s arms were tucked into the shelter of the furs draped over her shoulders and moved back. Vasilisa’s ministrations were bringing Sedna’s dull hair into shining life.

“She wanted to touch it,” Sedna began, as though there had been no interruption in the story.

“The girl and the wolf circled each other as the sun rose higher in the sky and the land’s rocky bones bloomed with lichen. The ice and snow receded, revealing cushions of moss and mats of grasses and wildflowers. By the time the sun’s spiral had nearly reached its highest apex, never falling below the horizon, the girl and wolf rolled and played together in the sedge and cotton grass, tasting one another’s scent and breath, and she knew his coat’s depth and warmth, which he shed in heavy white tufts.

One day he led her out to the edge of the summer ice and sprang into the water, disappearing in the green depths. For a moment, her heart faltered and withered. Then, a blunt black head with a white throat and eye patch emerged from the water and an orca rested its chin on the ice beside her. It looked sideways at her out of a small black eye and opened its mouth as though smiling, revealing an efficient row of sharp, peg-like teeth and a thick tongue.

‘Akhlut?’ she said, in wonder.

The creature nodded its head, slid off the ice and gamboled, leaping, rolling and slapping its tail in a spray of water that caught the sunlight like diamonds and streaked the blue green sea with foam.

Thus, the girl understood the mystery of the giant wolf tracks disappearing and reappearing at the ice’s edge.

When Akhlut clambered out of the sea, he shook himself vigorously, teeth bared in a grin much like that of the orca, and she knelt beside him and combed her fingers through his coat, pulling loose his winter hair and leaving behind a shorter, darker pelt. He luxuriated under her touch, panting.

Leaving behind clumps of discarded wet hair, they left the sea ice behind, and Akhlut led the girl to a place of springy turf protected by a stone the size of a snow shelter, and there he revealed his third and last form, that of a man.

And so the girl became a woman under the wakeful sun, and for a few short weeks she lived in joy with her mate in all his aspects, putting aside thoughts of the future and the expectations of her people along with her heavy winter clothing. She lay, unashamed and bare, under the sun in the stone’s kind shelter. and Akhlut wove saxifrage stems through her hair.

The season of midnight sun burned in everyone’s loins, and she knew the village would hardly sleep during the light days and nights. There would be singing and dancing, drumming, visiting, repair work and the fashioning of new tools, clothing and other materials. As snow shelters sank and melted, watering the earth, her people moved into hide tents, lashed against the unceasing wind.

Summer’s bounty does not last, and the people scattered across the tundra to collect cotton grass for the qulliq, willow wood and berries. A whisper of the girl playing with a large white wolf grew to a murmur of someone hearing lovers’ laughter from behind a rock, and someone else swore they saw a woman fondling the head of an orca near the sea ice. The village seethed and muttered. Life depended on knowing one’s place in the world of ice, snow, land and sea. Magic was a fearsome force, and might bring who knew what ruin to the people. The girl and her uncanny lover must be stopped.

The sun’s spiral sank and night’s cold shadow spread like a wing across the land. The hide tents flapped in the wind and the land’s fugitive green faded to dun and brown, russet and grey.

One day, the girl’s father begged her to accompany him in his sea kayak to fish. Once, they had been happy companions on the sea, fishing, laughing and telling stories. She had not fished with her father since childhood, but he insisted, saying he missed her, he hardly saw her these days, and she agreed.

They set out early one grey morning when the clouds were heavy and low and the wind quiet. For a time, all went well, and they harvested several pounds of salmon, a good start to their fall supply.

When they had been out for many hours, the wind increased and the sea grew choppy. The skin boat floated low in the water, heavy with fish, and the girl wanted to go home. All day she had thought of Akhlut, and she longed to be with him again. He would be waiting for her.

Her father lingered, checking one good fishing spot, and then another, talking about everything and nothing, yet casting frequent looks at the sea and sky, as though worried about the changing weather.

‘What are you waiting for?’ she asked.

‘Nothing. It’s a shame to go back before we carry a full load, is all.’

‘Father, we have a full load already!’

He didn’t meet her eyes, but looked back toward land, as though waiting for a signal.

Fear seized her, though she didn’t know what she feared. Something was wrong.

‘Father!’

He didn’t turn toward her but continued surveying the low hump of land and iron sky.

‘The hunters went in search of meat today,’ he said distantly. ‘Let us hope they find caribou…or skins for the winter.’

‘I did not know there was to be a hunt. Why didn’t you accompany the others?’

He turned to look at her then, and she knew. His task was to keep her out of the way while they hunted Akhlut. They had been seen.

In a haze of fear and rage, she struck out at him. Glowering, he shoved her with his paddle, and she toppled out of the boat.

The cold water stole her breath, and her heavy hides and furs weighed her down so she could hardly kick hard enough to keep her head out of the water. Gasping and choking, she grasped the side of the skin boat so he could heave her back in.

He struck her clinging hands with the paddle.

‘Father!’ she cried.

‘You shame me!’ he roared. ‘You, with your uncanny lover! You bring ruin upon us! You’re bad!’

‘Father, please!’

When the paddle smashed down on her fingers again, she let go, floundering in the water.

‘Unnatural woman! You forget your place and your people!’

She grasped the boat again, her legs heavy as lead.

‘I love him!’

He dropped the paddle and lunged for her with his knife in his hand, bringing the blade down in a chopping motion. She watched in bewilderment as her severed hand with its white fingers fell into the water in a spray of blood. She reached for them with her bleeding stump as they sank into the green water. They were her fingers. They mustn’t be lost in the sea. As though in a dream, she watched them sink, watched her raw stump reach for them. She could feel her cupped hand grasping, the skin of her fingers alert for the feel of what they sought, though they were no longer there.

With an angry roar, her father brought the knife down on her other hand, and then she thrashed low in the water, cold salt in her mouth, her ears singing. Her father’s face looked as hard as stone. The sea covered her eyes as she sank, too cold to struggle any longer, but still she gazed up, unblinking, until too much water flowed between them to make out his features any longer.

Her hands, white and graceful, sank slowly with her. Blood swirled and congealed in fantastic shapes, rolling and turning, forming into spirals around her as she sank. She saw a large dark eye, curious and gentle. She saw a sharp, curving tusk beside stiff whiskers. She saw an endless hairless body, thick and massive, with a huge tail. She saw a twisting spike in a smooth, blunt head, and shades of white, grey, black and brown skin and fur.

Down and down she sank, escorted by the whirling creatures around her, and she realized suddenly she was not drowning, but breathed as easily beneath as she did above. Her hands were gone. Her father and the skin boat were gone. Akhlut was surely gone. Her old life was gone. Once again, she was born in a cloud of blood, but this time she was not alone. This time, her bone and blood and flesh peopled the sea with walrus, seal and whale.

So Sedna, who never bore a child and knew a lover only for a few short weeks, became the Ice Mother, the one who feeds the animals above and below. She feeds the humans, too, but grudgingly, for they murdered her lover and cast her out, and she demands gifts and attention before she releases an animal to feed them. The shamans must undertake the long and dangerous spirit journey beneath to propitiate her, and she insists they comb her hair and perform other services in exchange for food.”

Clarissa, absorbed by the horror of the story, realized Sedna wept. Her tears did not distort her voice, but the fur around her was spotted with moisture. During the story, Vasilisa finished braiding Sedna’s hair and wrapped it carefully around her small head, leaving her slender neck and the finely modeled cheeks exposed, though her head remained bent and her eyes lowered, as usual. The tattooed lines on her chin gave her an exotic look.

“Do your hands pain you?” Vasilisa asked, and Clarissa felt shocked. The question seemed an inadequate and inappropriate response to the terrible story. What did one say to someone who had endured such anguish? How did one acknowledge such pain and begin soothing it?

Sedna appeared surprised, too. She raised her head and looked at Vasilisa over her shoulder. Her dark eyes still smoldered with pride and rage, but Clarissa saw respect there, as well. She remembered suddenly that Vasilisa had been maimed once and had a malformed foot as a result. Her question was genuine. Clarissa wondered for the first time if Vasilisa’s foot pained her, and that was why the question occurred to her.

“Sometimes,” said Sedna. “Sometimes I dream of Akhlut. He comes to me as a wolf, and I reach out for him, expecting to feel the softness and depth of his winter coat, but my hands are not there and my stumps are bleeding so his white fur is stained with blood. When I wake, my hands itch and tingle and throb as though warming after frostbite.”

“Are you certain he’s dead?” asked Clarissa.

“He would have come to find me if he could have,” said Sedna.

Clarissa nodded.

“So, you are Ice Mother, but no one cares for you. Your children inhabit the sea. Your people exiled you and fear you, though they depend upon you,” said Vasilisa.

“The shamans visit me only when the people need of food,” said Sedna.

“No one loves you for yourself. You must feed all, but no one feeds you. You are alone.”

Vasilisa’s voice remained steady. Clarissa felt surprised at her cruelty. Surely comfort would be kinder, some kind of reassurance, some hope Sedna was loved apart from her ability to provide food, even if it was false hope.

Sedna sprang violently and unexpectedly to her feet, making Clarissa flinch and gasp. It was the first time she’d seen her stand up. The skins around her shoulders slid off, leaving her pitifully thin and naked, but her twisted crown of hair gave her a regal look. She ran lightly away from the camp, bounding as though weightless, making a keening sound of rage and grief. After a moment she stopped and bent, bracing her mutilated forearms against her thighs, sobbing and retching as though she would tear herself apart. Clarissa made as though to follow her, but Vasilisa laid a hand on her arm and shook her head. “Let her be,” she commanded.

Beyond Sedna, the heavily-laden figure of Pim appeared, emerging out of the white and grey landscape.

MORFRAN

By the time Marceau, Poseidon and Morfran returned with as much fish as they could carry, Pim, Vasilisa and Clarissa had erected the tent, using the whale’s skeleton as support, and lashed it firmly against the wind. The qulliq burned within it, protected from drafts. Tonight, they would sleep warmer. Morfran’s hip ached in the cold, and he was relieved to see better shelter. He had limbered up in the water, which was warmer than the air, but he knew he’d be stiff and sore after another night on the stony sea floor.

He’d been surprised to find Sedna on her feet, staring toward the strangely suspended sea, when they returned to camp with the fish. Wrapped in a beautifully tanned polar bear skin that dwarfed her slight figure, he thought she looked like an ice queen with her shining black hair bound around her head.

She ignored everyone around her, as aloof and withdrawn as if she were alone, and they didn’t disturb her as they entered the camp, but he knew she must have seen the fish.

He wondered if she would allow him to feed her again this night.

He wondered what they were doing here, and how long they would stay.

He thought of Sofiya with longing, and the winter birch wood. He thought of the smell of birch oil and the sauna’s heat. He hadn’t imagined a landscape so bleak or a place of such delicate beauty. The poverty of color, mountains and trees emphasized the textures and shades of ivory and grey. The cold, empty wind intensified the smell of the melting blubber in the qulliq and the ever-present smell of fish, skins and meat.

Marceau and Poseidon appeared content, unbothered by the cold and equally at home in the water and out of it. They spent hours talking to the selchie, learning everything they could about this northern sea.

Morfran, quiet and self-sufficient by nature, kept his questions and uncertainties to himself and focused on the one thing he felt sure of.

It was his task to feed the Mother.

The Samhain ritual he’d undergone with Rumpelstiltskin under Odin played over and over again in his mind. For weeks he’d fretted, not knowing how to express positive male energy in the world. He knew Vasilisa felt the same frustration and asked the same questions. How could she express the energy of Mother? Everyone around them appeared to have a role and a contribution.

Here, in this place that felt like the end of the world, lived the Ice Mother, wary and bitter as a starving wolf. Here was the division he’d seen and heard of elsewhere: the sea withdrawn from the land, the people rejecting the spirit of their faith, and the connection between animals, humans, ice, stone, and water collapsing.

He could not begin to fix it all. He didn’t even fully understand what needed fixing. But Sedna, handless, smoldering with rage, alone, was hungry, and he could feed her. She allowed him to feed her.

So, feed her he would until he knew it was time to do something else.

That night, they ate in the tent’s shelter, and the qulliq seemed as warm as a campfire when they were shielded from the persistent wind. Sedna did allow Morfran to feed her, and she ate as much if not more than she had the day before. It amazed him, how much food she could take in one sitting. He alternated offering strips of walrus meat and blubber with salmon, and she ate with avid concentration. Pim brought her cup after cup of water.

Two days of food, water and attention had helped her regain some humanity. Thin and fierce, she nonetheless possessed a new dignity and Vasilisa’s work on her hair revealed a prideful beauty. She no longer looked like a feral starveling. Her cracked lips healed. She even met his eyes directly once or twice as he fed her, and he smiled at her, hoping to convey friendship rather than pity, which he knew she would resent.

He took care to eat nothing until she was satisfied, as a gesture of respect and willingness to serve. Pim snatched a mouthful here and there in between bringing her water, and the others ate freely, chatting comfortably.

Morfran liked Pim. He was direct and thoughtful, two qualities Morfran appreciated. His instincts were good, too. Morfran admired the way he’d picked up on his lead when they first spoke with Sedna. Another man might have talked over a stranger, displaying condescension, pity or impatience with Sedna, but he had watched and listened and joined Morfran in approaching her with an offer of service, asking nothing in return.

The night before, they had talked as they worked on cutting up the walrus meat and scraping the skins. Briefly, Morfran described the Samhain ritual and explained his recognition of the need to feed Sedna, a starving mother if ever there was one. Pim listened carefully and asked good questions. Morfran looked forward to a lengthier talk. He missed the companionship of men his own age.

Dealing with the cold demanded calories, and they ate heartily. Sedna was still at it when Vasilisa declared herself replete and offered a story while the others finished. The company applauded the offer, and Vasilisa told a story about Nephthys, Lady of Bones, who lived in the desert between the worlds.

Morfran had heard a great deal about Nephthys when he visited Rowan Tree from his friends, Eurydice, Kunik and Maria, each of whom had visited the desert between the worlds. He himself had met Nephthys briefly, at an Ostara ritual in a circle of story with Baba Yaga.

Although ancient and powerful, Nephthys appeared in the form of a child. It was said she was so old she had passed through old age and begun life’s circle again. It felt strange to sit in a skin tent in the northern wastes, the cold wind scouring the dry sea bed and trying to tear the hides from the whale’s skeleton, hearing about an ancient woman-child of the desert. Strange, but somehow fitting, too, because Nephthys, like Sedna, contained a kind of elemental female power. Her skin was tattooed, as Sedna’s was, though her tattoo circled around an arm like a snake. The desert, in its way, was as harsh, unforgiving and mysterious as this land.

Marceau, Poseidon, Clarissa and Pim sat spellbound as Vasilisa described a woman lost in the desert, Nephthys finding her and teaching her to gather bones, lay them out and pour spirit over them to reanimate herself.

“No bone is ever so lost, or broken, or hidden that Nephthys cannot find it,” Vasilisa finished. “Everything lost is found again in the desert between the worlds.”

Sedna, finished, wiped her mouth with her forearms, the rich fat from the blubber glistening on her skin in the qulliq’s light. Morfran, watching her and imagining drifting above Nephthys’s desert with the vultures, had a sudden idea. He shot a glance at Vasilisa, who watched him with a small smile, and their eyes communicated question and answer.

His heart leapt with the rightness of the next thing, clearly laid out before him. Pim took his place with water for Sedna to rinse her mouth, and Morfran, smiling to himself, began his own meal.

“I suppose every place has its stories, then?” Pim asked. “The seas, the desert, the ice, the forests and the mountains?”

“The stories of place and people mingle until their voices become the same,” said Poseidon. “If you would truly love and understand a place and its people, you must learn its stories and, over time, add your own.”

“Do all people have a Mother, as we have the Ice Mother?” Pim asked.