The Hanged Man: Part 1: The Hanged Man, Part 2: Mabon (Entire)

In which you can read without interruption ...

Part 1: The Hanged Man

The Card: The Hanged Man

life in suspension; a pause

It begins with the Hanged Man.

Harvest passed through his hands, but they’re slack and empty now, scarred from picking, mowing and cutting the yield. He existed in the kiss of stone and blade, the rapturous sickle shape of the scythe. He inhabited callus, gash, thorn, wasp sting and torn fingernail. His sweat oiled the handles of a thousand tools. His blood and seed oozed out of discarded sinking fruit, smelling of rot, on the parched stubble.

Now comes peace after mighty effort. Blankets of snow are soon to cover November’s bony bed. The Hanged Man rests, dried and diminished in loose nakedness, dangling upside down by one leg from a skeletal bough. The snake, Mirmir, wraps around the branch, anchoring the Hanged Man, his flat head swaying near the man’s gold-ringed ear.

Mirmir murmurs of what might be and what might not be, what has been and what has not been, of time past and coming again soon. He whispers of worlds like glowing marbles turning through dark space, blue and green, grey and brown. Each world is a long, long story; each life a shorter one. The stories are bound, one to another, a net of star and crystal flung across the cosmos, linking one world to another so the leaves at the top of Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, intertwine with the stars, each to tell, each to listen.

In this tree, on this small planet called Webbd, a crimson cloak hangs, a thin worn leaf of glory, sieving chill wind, fluttering, as leaf, snake, man, star and story revolve in endless dance, here at the turning point.

The Hanged Man listens. And he smiles.

Part 2: Mabon

(MAY-bone or MAH-bawn) Autumn equinox, the balance point between summer solstice and winter solstice. The second of three harvest points in the cycle, a time to complete tasks, measure success, give thanks and prepare for winter.

The Card: Two of Wands

growth, movement, action, clear seeing; division and boundaries

CHAPTER 1

PERSEPHONE

“Stop with the flowers! No more flowers!” Persephone glared at Demeter.

“But I love you!” Demeter’s lip trembled.

“Mother,” said Persephone between her teeth, “I’m suffocating. You’re embarrassing me. You’ve wrapped me up in a stifling blanket of flowers and fruit and grain and I hate it! I want to be free!”

“Free,” said Demeter, her voice rising. “Free from what? I’m your mother, young lady. Your mother! You’ll never be free from that!”

“Don’t count on it!” said Persephone in fury, and slammed the door behind her.

Not for the first time, Persephone took refuge in the comforting company of the horses. These days she often pulled herself onto a broad back to amble through field and forest, restless and frustrated. Sometimes she came across people working the land or caring for flocks and herds, and stopped to exchange country talk of weather, crops and animals.

Harvest ushered in the season of the Wild Hunt, when storms swept across the sky and stole away the souls of the dead. A night belonging to the Wild Hunt by long tradition approached, and farmers and shepherds made ready to protect their animals and families.

On nights when the Hunt rode, Demeter made sure she and Persephone were well within doors. Persephone remembered the sound of those wild nights when the gale thrashed in treetops. The iron hooves of the horses, clamor of horns and hounds, and shouts and curses of the Hunt swept through the dark sky in a wave of tumult, ominous and exciting.

Odin, Wind God, summoned the Hunt and autumn storms, and Persephone knew his daughters, the Valkyries, rode with the hunt. Might Odin provide her with a teacher or a path to the future?

The autumn days grew shorter, Demeter preserved a hurt dignity and Persephone longed for a life of more than abundance and beauty.

HADES

Hades brooded on the lot he’d drawn with his brothers to decide who would rule each portion of Webbd. Poseidon drew the sea. Well and good for him! Plenty of movement and life there. Plenty of company and beauty. And Zeus drew the sky and was never seen anymore. Typical. Zeus always grabbed what he wanted and he always wanted the best of everything. He would appropriate the highest seat in the stadium. Hades himself drew the Underworld. Certainly, he possessed the worst part of the bargain! And now the eternity of his life was to be nothing but cold bones and death. His soul sickened. He longed for the sight of something more than rocks and the spectral dead. His power was empty. Despair and rebellion swallowed him.

One of Odin’s wolves carried an invitation from Odin to Hades to ride with the Wild Hunt and gather dead souls lost in storms and winds of the lengthening nights. Odin needed Hades to oversee the work, as the dead were his responsibility. Hades considered, shoulders hunched, while he sat by the fire. More of the cursed dead, as though the place wasn't already filled with them! Still, a chance to be back in the world with a strong horse beneath him, the sound of hounds and horns and wind in his face! He accepted.

MIRMIR

“In all timess and placess live thosse who ssee what’ss hidden,” Mirmir whispered, sounding like dry leaves rustling. “Their ears hear the prayers of the heart better than the prayers of the lips. They visit altars in forests, on moors, on hearths; altars decorated with symbol and rune, a pack of shabby cards, a handful of sticks or bones. Old women wait at crossroads with a gift. Uncanny peddlers spread their wares. Crones spit on a handful of marbles like jewels, galaxies in their eyes. Musicians walk with enchantment in their packs. And an old man with a staff, a cloak, and a weathered and worn hat tilted to hide an empty eye socket, wanders here and there, seldom speaking, his one eye seeing more in a day than any other two in a lifetime.”

“Odin,” sighed the Hanged Man. Sunlight shone through the tired gilt of a few remaining leaves and fingered his thin hair.

“Who knowss the thoughtss of thosse collectorss of sstoriess and prayerss?” Mirmir continued. “Who can gauge the depth of their wisdom or humor? How far behind and how far ahead do they see? And if Persephone, in her frustration, and Hades, in his anger, are offered a choice, a risk, a chance to change their lives, will they take it?”

“Tell me how it was,” said the Hanged Man.

PERSEPHONE

The night of the Wild Hunt, Persephone resolved to spend a pleasant evening before the fire with her mother. She praised the bread and honey and drank barley water, Demeter’s favorite, without complaint. They sliced apples for drying and Demeter relaxed into loving maternal approval.

Eventually, Persephone yawned and suggested bed, watching as Demeter checked to see that windows and doors were locked and barred.

While her mother breathed in sleep, Persephone plaited her long bright hair and wound it around her head under the hood of her woolen cloak. She wore sturdy country clothes, thick and warm. She made her way out of the house and into the night.

The moon, Noola, pale and tired, lay on her back. Later, Cion would rise, filling the sky with her silvery body. Persephone moved warily away from the cottage into a grove of trees. A breeze rose and rustled the highest leaves. A raven croaked unexpectedly, like a signal. Persephone came out of the trees’ shelter, her breathing easing as she put distance between herself and her sleeping mother. She walked across the long rolling flank of a hill, under open sky. Here she could see and be seen. She stood with her face raised. A gust of wind snatched the hem of her cloak and bellied it out like a sail. In a sudden rush of wings, a raven came to rest on her shoulder. She gasped and flinched, but it gripped the wool of her cloak and held on.

She heard a sound as though of mighty gates opening. From far up and away came the desolate calling of wild geese on the wing. The wind rose and rose again, and Persephone heard baying hounds, hooves of galloping horses and hunting horns, echoing and magnifying the call of the geese. The Wild Hunt swept across the sky in a dark wave of wind, and something fierce and exultant leapt in Persephone. She heard herself cry out, a wordless sound of triumph and strength, and spread her arms as though in command.

HADES

Fierce joy filled Hades. He gloried in the night, the Hunt, the feel of a horse between his knees. How long, how long since he’d been out in the beautiful world? For the moment, his gloom and resentment were forgotten. He added his voice to the voices of the Hunt and urged his horse on. An unkindness of ravens flew above the hunt, their grating calls contributing to the din.

Odin struck Hades on the knee with his staff and pointed with it at a figure on the long slope of a low hill ahead. At once Hades wheeled away across the hill’s flank. Wind tore at his beard and the horse's mane and tail and he grinned into it. The figure stood quite still, arms upraised, and as he swooped down toward it a black bird took off from its shoulder with a harsh cry, just audible in the gale, and flew after the Hunt. Hades grasped one of the upraised arms, not troubling to be gentle, and hauled the figure up behind him. He felt arms come around him in a tight hold, the warmth of a body against his back, and a head tucked between his shoulder blades, sheltering from the wind. With a cry, he loosened the reins and set the horse at a thunderous gallop to rejoin the hunt.

Hades gave no thought to the rider behind him. He stayed quiet and out of the way and Hades all but forgot his presence in the lust of the hunt and black passion of night sky and storm. Over and over he winded his horn. He shouted until he was hoarse. The hounds ran at his horse's feet, baying and howling at the scent of each soul. The horse fought bit and bridle, reared, screamed, outran the very wind, but couldn’t escape the will and strength of its rider, and Hades was drunk with his power over the great animal. The Hunt flowed out behind its leaders like a clamorous dark wing, and if more than lost souls were plundered, Hades took no notice.

PERSEPHONE

For some minutes, Persephone only concentrated on staying on the enormous horse. She could hardly straddle it. Its speed, combined with the gale of wind and storm and sounds of the Hunt, deafened and blinded her, snatching away her breath. She wrapped her arms around the man in front of her and hung on. His broad back provided some protection from the surrounding chaos and she clung to it, resting her cheek between his shoulder blades.

She could see the Hunt’s net sweep across the sky, gathering lost souls from the storm’s embrace, along with other flotsam and jetsam and a hailstorm of aggies and allies, catseyes and devil’s eyes, tigers and bloods and pearls, for Odin’s collection of marbles. She knew the one-eyed old man was a fearsome marble champion, a fact which many felt sadly diminished his dignity.

Persephone never forgot that ride, but even the most fearsome night must end in dawn. As the sky lightened at last, Odin led the Hunt to food and drink and the great hall of Valhalla.

Valhalla! Persephone leaned to the side to see around the bulk of the man in front of her. The gale was spent and dawn approached. Ahead, tucked in a hollow in the hills, she saw an immense hall, shining and golden. In moments, the Hunt clattered onto a cobbled courtyard. Men came from every direction. The hounds panted, tongues lolling, and horses stood with lowered heads, tails and manes in a wild tangle, hides streaked with sweat and rain. As the rider in front of her dismounted, Persephone slid off the broad back of the horse with him. In the crowd of beasts and men, with horses and dogs being led this way and that, none noticed her. She leaned for a moment against the horse's massive flank, her knees weak and trembling. The huntsmen followed Odin through an enormous set of carved doors under the snarling head of a wolf and into the hall. A stable boy took the horse’s reins and Persephone pulled her hood further down over her face and hair and followed the tired animal into the stable.

She revived in the familiar atmosphere. Generous stalls were deep bedded in clean straw. She saw a room filled with tack and saddles; several faucets producing clear, cold water; and a cavernous room and loft for storage of hay, straw, grain and other such essentials. Wary stable cats lurked everywhere amid forks and buckets, grooming brushes and combs, hay hooks and hoof picks. The good smells of horseflesh and manure greeted her nose. Grooms and boys hurried in every direction as each mount was led to a stall, rubbed down, brushed, fed and watered. The bustle gave way to the murmurous talk between horses and men who love them.

Persephone took advantage of a pump in a quiet corner, drank, and washed her face and hands. In the tack room, she found a lump of cheese and half a loaf near a partly-mended bridle, left, she supposed, when the Hunt arrived. She burrowed in between towering stacks of straw and ate her stolen meal. The stable grew quiet as the horses were left to rest. Sun shone in through high windows.

When quiet reigned, she made her way to the stall where the horse she’d ridden stood. She couldn’t guess why the rider took her off the hillside near her home, but she couldn’t spend the rest of her days hiding in this stable and Odin had taken no notice of her whatever, so she’d stay with the black stallion’s rider.

The horse dozed, a hind foot cocked. His hide shone, dry and clean. His feed bucket was empty. He raised his head and pricked his ears as she entered the stall. She passed her hands over his smooth, warm hide, scratching in the roots of his mane, murmuring the horse talk she’d learned as a young child in her mother's stable. He blew a warm breath down her neck, rubbed against her with his hard head, and then quieted again into somnolence. She settled into deep straw in a corner, wrapped in her cloak. She thought with a wry smile of what Demeter would say if she knew how her daughter had spent the night. She hadn’t left a note because she hadn’t known what would happen, and now she was sorry. Her mother would worry.

A raven alighted on the stall door and she remembered the sudden clutching weight on her shoulder on the dark hillside the night before. With a flap of wings, the bird moved to the horse’s broad back, strutting from rump to neck and tweaking a lock of mane in its beak. The horse snorted, shifted his weight, and cocked the other hind foot. The raven flew away.

Persephone rested, waiting for what would happen next.

***

Persephone roused out of half sleep. She heard new activity in the stable. The horse in whose stall she’d taken refuge snorted. She heard men's voices, the running feet of stable boys, the sounds of stall doors opening and latching and the horses themselves neighing and pawing.

Persephone took off her cloak and shook it free of straw. She tucked in strands of her unraveling hair, straightened her clothing, put the cloak back on and drew it over her head. She approached the horse, who greeted her with an impatient push of his head, and soothed him with soft words. She rubbed his forelock and between his ears, smoothed her fingers down his long muzzle. The latch on the stall door released and opened, but she didn’t turn. There was silence.

HADES

In the great hall of Valhalla, Hades and the other hunters refreshed themselves and took their ease at a long table. At either end of the hall, fires burned in fireplaces large enough to accommodate a spitted boar. The rafters of the hall were made of interlaced spear shafts and doors lined the walls. Odin sat in a carved wooden chair at the head of the table, two ravens perched on the back of the chair, one at each shoulder. He spoke little and listened much. Valkyries moved back and forth with empty plates and serving dishes, loaves of bread, rounds of cheese, tankards of ale and mead and platters of meat.

Hades sat at Odin's right hand, wordlessly eating and drinking. For a time, he’d escaped the confines of his life in the Land of the Dead, but soon he must go back and he didn’t know how to endure it. He lifted his tankard and saw Odin watching him. He set down the tankard without drinking.

"All of my life is death," he said to Odin. "How shall I live a life of death?"

"My friend," Odin replied, "all of life is death, and all of death is life. Don’t you understand you stand with one foot in each? How many can endure shadow and give birth to light?”

Hades shook his head.

"You haven’t yet begun to learn the secrets of your kingdom," said Odin.

"Is the price of my power to possess no companion, no warmth, no fellowship? Everyone fears and dreads me. My name is shunned and forgotten and I’m known only by the name of my cold realm!"

"Ah, well," said Odin, relaxing into a smile, "Who can tell?"

When every belly was full, the Valkyries cleared the table, swept the floor clean and set benches straight. Hades lay down on a pallet and slept. Sun shone through the windows, its light creeping across the floor and the sleeping men.

***

Hades woke with the knowledge it was time to return to the Land of the Dead. He accepted the offer of half a loaf and some cheese and a tankard of Odin’s mead, but refused to sit. He stood before the fire and ate alone. The hall grew dark. The Valkyries lit torches, stacked sleeping pallets in a corner and fed the fire with logs. The Wild Hunt made ready to go their separate ways. Hades thanked his host with a minimum of courtesy and walked out the carved doors to the stable. A boy directed him to the stall housing his stallion.

The big black horse was one of the few creatures Hades loved. He had no use for him in the Land of the Dead and boarded him in the Green World. The horse, like his master, was of uncertain temper and enormous strength, and suffered few to approach and none to ride him but Hades himself. Yet here, in the stables at Valhalla, he found the stallion being fondled and petted and enjoying it like a pampered lapdog. He was amazed and then outraged, drawing his black brows together in a scowl. He hadn’t thought again about last night’s passenger, but now remembered the cloaked figure he’d pulled up behind him early the night before. He’d only had one glimpse in the storm’s tumult, but this must be the same lad.

“What do you want here? Be off!”

PERSEPHONE

Persephone turned, her face shadowed by her hood. She saw a broad chest, a black beard, a fearsome scowl, hands clenched into fists. The horse nickered in greeting behind her. She straightened her shoulders and stiffened her back, but said nothing. She knew her first word would give her away. She felt the horse’s lips at the back of her neck as he gripped her hood in strong yellow teeth and pulled it off her head.

Hades’ jaw dropped. His gaze roamed over her body. He took a step toward her, his eyes hot.

Persephone, maiden though she was, didn’t mistake his intention. Rage swept through her. Was her worth always to be reduced to her beauty? Was she never to be more than a pretty plaything? Hades grasped her by the same arm he’d taken hold of on the windswept dark hill the night before and it felt bruised and sore. She lifted her other hand and slapped him as hard as she could on the patch of skin high on his cheek above his beard.

Hades paused. “Do you know who I am, girl?”

“I don’t care who you are! Keep your hands off me!”

They glared at one another.

“I’m Hades, Lord of the Dead and the Underworld!” he informed her, not without some pride.

“It’s a pity your great title doesn’t come with better manners! I suppose the dead don’t care if you behave like a brute!“

She saw with satisfaction she’d roused his own anger. “You … How dare you? You speak to me so? I’m the Lord of Death! I wield the power of Death!”

“So you said,” she replied. “Congratulations. Tell me, then, Oh, Lord Hades of the Dead and the Underworld, what do you know? Are there many mysteries and secrets of your realm?”

He looked at her with astonishment. She recognized his confusion and seized the opportunity. “My lord,” she said, “Take me with you. I want to learn. Teach me.”

“You don’t know what you ask!” he blustered. “You can’t come there.”

“I’m not afraid! You endure it, why can’t I? I tell you, I can do so much more than I’ve done! I can be so much more than I’ve been! Let me try!”

His anger appeared to drain away, and she thought he suddenly looked tired.

“Very well,” he said, unexpectedly capitulating. “I’ll take you with me.” He left the stall and shouted for a stable boy to bring tack and saddle the horse. When the boy came, Persephone dismissed him. She dressed the horse herself while Hades watched. The stallion nickered and lipped at her as she moved around him. He opened his mouth for the bit and stood docile and quiet as she cinched the saddle, making sure no strap caused discomfort.

Persephone took the reins and led the horse out of the stall and down the aisle. The cool evening filled the courtyard. Hades mounted and pulled Persephone up behind him. She put her arms about his waist, holding him lightly. He was silent as they rode, and she watched the light fade and the sky darken while the stars lit like candles.

They rode through the night. As morning approached, they came to a massive pair of closed gates. Hades dismounted and Persephone slid down to stand beside him. Hades gave a shrill whistle and a man came running from a nearby cluster of buildings. Hades tossed him the reins. The man gaped at Persephone, showing a mouthful of discolored teeth. Persephone took no notice, but ran her hands over the stallion’s neck and down his long nose in a farewell caress. The sound of his hooves moved away as the man led him to his stable and a meal.

“These are the gates to my realm,” said Hades. “You can’t come any further.” Persephone stood silent and stubborn beside him.

“You can’t come with me!” he said, exasperated. “You don’t know what it’s like! I’m no teacher of girls! I hate the place and I hate my life here. Be off with you! I don’t want you!” He drew his brows together and scowled at his boots.

“I’m coming with you,” she said. “Show me.” She laid a hand on his arm.

He stepped forward and the gates swung open to admit them.

Later, Persephone’s memory of the journey was of blurred and soft shadow with flashes of extraordinary clarity. Hades took her hand and she never forgot the feel of his clasp. At one moment, they seemed to be children traveling together into an unknown and fearful world. At another she felt herself to be his support and comfort, but she also felt protective reassurance in the clasp of his fingers, as if he sought to tell her without words he would stay by her.

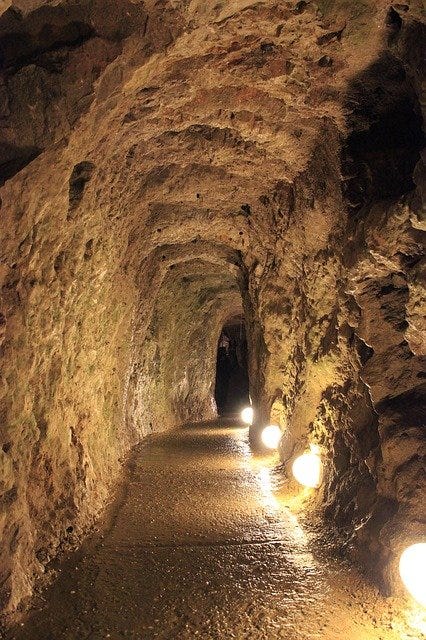

The path twisted, leading them through many gates and doors, Hades speaking now and then a word of command to open their way. She walked beside him and watched with wonder as color and light faded out of the world. Shadows grew until all was shadow and unrelieved bare rock. No insect, no sound of bird, no green of plant or color of flower softened the landscape. She had never imagined a place like this! Yet she didn’t feel afraid or appalled. She’d lived all her life surrounded by careless abundance and beauty, and now discovered a kind of relief in the barren simplicity around her. Flesh was beautiful but the hidden mystery of bone beneath flesh seduced her. Something in her expanded and breathed deeply.

They came to a river, the other side lost in dim shadow. Hades whistled and a small boat slid into view, lit by a lantern. At its helm sat the oldest, most desiccated and wizened human being Persephone had ever seen. He looked like an ancient piece of leather, tough and indestructible. His face was seamed so deeply his features were indistinguishable. A small, lizard-like creature glowing like coals in a fire, orange and sulfur yellow, crouched on his knee.

“My Lord,” he croaked, bowing his head, and Hades, still holding Persephone’s hand, stepped into the boat.

The old man dipped the oars and the boat moved across the river. This was not a chuckling, murmuring, splashing, living river, gleaming in light, but implacable, cold and powerful, flowing with a single continuous rushing sound. Persephone wondered at the old man’s strength in oaring the boat across it. It looked fast and deep and she wasn’t tempted to trail her hand in it. Glancing at the old man, she saw him watching her, but his eyes were a brief and far-away glimmer in the lines of his face and she could read no expression there. His face changed. His mouth widened and he gave her a toothless smile, but whether in kindness or derision she couldn’t tell. She gave him a slight smile in return.

River and boatman left behind, Hades led her along a path climbing and falling through narrow ways and caverns. Around them she heard murmuring and rustling, whispering and slight movement, as though thousands of leaves spoke together. As Persephone and Hades walked through this gentle susurration the sound ceased, beginning again in their wake. “It’s the sound of the dead,” said Hades in a low voice. They’re afraid of me and fall silent when I approach.”

“What do they talk about?” asked Persephone.

“I don’t know,” he replied.

“What do they do here? How long must they stay and then where do they go?” She looked at the cold shadowed rock around her. The living world seemed like a faded dream in this place.

“It’s the Land of the Dead! They do nothing, for they possess no bodies. They whisper and murmur and fear me. They move from here to there. There are many ways out and many ways in. Even I don’t know them all. Sometimes they leave, I don’t know how and I don’t care! The place is always filled with them. They’re terrible! I don’t know where they go. What does it matter?”

“It matters because you’re their midwife from life to death and from death into the next thing! It matters because they’re your people!”

His face closed and he turned away without another word. Persephone glared at his back. He was impossible! Whatever she learned in this place wouldn’t be from him. Yet there were so many unanswered questions and so much to understand. Her heart went out to the dead. To come from the green living world to this! And to find no guide, no help, no way forward. Yet Hades himself said there were many ways in and out of this place.

Surrounded with so much life and being young and strong, she’d never thought about death and what lay beyond it.

They came into a hollowed-out cavern. A fire burned and she smelled roasting meat. She saw a throne-like chair and a table set with dishes and cups. Skins softened a cold stone floor. In the shadows against a wall lay a mattress and a heap of blankets, in the manner of a great hall where the household slept together before the fire. But here there existed no household, though a man tended the fire. His body looked pale and dim. Hades followed her look.

“I can give them form,” he said. “That’s Kadmos. He lived as a servant in life and he serves me well enough now. I don’t require much in this place.”

The man inclined his head towards Persephone and she smiled at him, but he seemed not to see.

Persephone became of aware of deep weariness. She ate and drank but hardly tasted what she put in her mouth. She longed for sleep and sat drowsing before her cup. Hades shook out his mattress, putting it near the fire and making it up with blankets. He extinguished torches so the cavern flickered with firelight and shadow. He took Persephone by the arm and led her to the mattress. She reached up and pulled pins from her hair and her braids fell down her back in two golden tails. She lay down and fell asleep, curled on her side like a child, before he finished covering her.

HADES

Hades turned his chair to face the fire and brooded in front of the flames. The girl slept, the gentle rise and fall of her breath making the rich color of her hair gleam in the firelight. He thought of her questions. He felt ashamed because he couldn’t answer them. He thought of Odin saying he didn’t know his realm, and recognized truth. His hatred of the Underworld, his longing to be free of it, and his jealousy of his brothers’ lots killed any curiosity about his own portion. But now, alone before the fire, he wondered. She had said he was a midwife and these were his people. He snorted to himself, thinking of the figure of a bent old crone he associated with a midwife. Yet perhaps his role was similar to such a woman. What did the dead whisper of?

Tomorrow he’d find out. Tomorrow perhaps they’d find out together. But tomorrow would she beg him to take her back to the Green World? Would she be sick and horrified to find herself here with him when she awakened? The moment when he might take her for his pleasure and turn away was gone. He respected her courage and defiance too much. Who was she? He realized he still didn’t know. He didn’t even know her name. Even if she wished to stay for a time with him, her people would demand her return.

PERSEPHONE

The Underworld knew neither morning nor night, but Persephone woke feeling rested, though grimy and travel worn. Hades called for a female servant and a woman came to Persephone, dim and transparent as the manservant who greeted them the night before, but neat and with a shy smile for her. Hades himself had business to catch up with after his absence. The woman led Persephone through corridors and caverns and after a time they stepped from a narrow way into a large cave filled with steam and a mineral smell of hot water. Persephone heard the gentle gurgle and bubble of a spring. The woman helped her out of her clothes and unbound her braids, exclaiming with pleasure at the weight and color of Persephone’s hair. As Persephone stepped into the rocky pool, the woman moved to leave but Persephone asked her to stay and talk. She shook out and folded Persephone’s clothing and then took up a sponge and a basin of soap and helped her wash her hair.

Encouraged by Persephone’s gentle questions, the woman spoke of working in a large wealthy household until she had become ill. Her master gave her a bed and what care the household could provide, as she’d served him well most of her life. Death came after a time of great pain and suffering. She laid a hand on her belly, remembering.

“Now I’ve come here,” she said, “and I’m fortunate, for I’m given something to do. Most of the dead don’t know who they are or what they’re for. Some believe there’s more after this place, but none know how to find it. We wonder if all we were and felt and did was a dream without meaning. We miss those we left behind and seek those who came before us, for we’re so lonely. Many despair in this place.”

“And what would you do with your death, if you could?” asked Persephone.

“Lady, I would speak my name again,” the woman said. “I’d tell the story of myself, what I learned, what I rejoiced in, what gave me sorrow. I’d speak of my regrets and mistakes and the shape of my days. I’d tell of those I loved. Then…” She leaned forward, filled the basin and poured it carefully over Persephone’s head, rinsing soap away. Steam from the hot mineral water enclosed them. Persephone felt the aches in her body soothed.

“Yes?” she encouraged as the other fell silent.

“I’d be free,” said the woman in a low voice. “I’d be free to serve only myself.”

Persephone dried herself on a length of cloth. The woman brought a bowl of scented oil and massaged it into her body, combing it through the thick tangle of hair with her fingers. Persephone donned her clothes and they returned to Hades’ chamber. She sat on a low stool before the fire while the woman plaited her hair, pinning it around her head in a crown.

When her hair was neat, Persephone rose and turned to face the woman. “I’m Persephone. Lady, what’s your name?”

“My name is Frona,” said the woman, and bowed her head. Persephone embraced her. “Frona, will you come to me soon and tell me your story, from beginning to end?”

“I will,” replied Frona. She turned and left the chamber.

When Hades returned for a meal, he found a fire burning, the hearth swept, mattress and blankets tidied away and the table set for two. Persephone greeted him with a smile and held out her hand to him. He took it briefly before dropping it and turning away.

The manservant, Kadmos – Persephone had spoken to him now as well -- brought food and drink to them. Persephone waited until he was gone before speaking. When they were alone, she said, “Now it’s time to talk about the past and future.”

As she spoke, she watched him turn his cup around and around between his fingers, his eyes on the torchlight playing on its silver surface. She told him about her life with Demeter, her boredom and loneliness and longing for something of her own, something private and apart from her mother.

Then she told of her day and her talk with Frona. “I want to hear her story,” she said, “and Kadmos’s, too. I want to help them go on. I want to understand this place and what it’s for, how to use it. There’s mystery here, and power. This is the other half of my life with my mother. That was sunlight and warmth and this is shadow and cold. Together they make a whole I want to know and understand.”

He didn’t speak. The fire burned quietly. Persephone, who hadn’t paused to eat while she spoke, broke a piece of bread from the braided barley loaf she’d baked earlier in the day and spread it with honey.

Hades never raised his gaze from the cup between his fingers as he began to talk. His face softened and he looked younger under the wild black beard as he related drawing lots with his brothers to decide who would rule which part of Webbd and his first journey to the Underworld as its master. He spoke of loneliness and bitterness, his longing to be free again in the living world. “Even my name is now lost,” he said. “I’m so feared my true name is never spoken, lest it summon me. Now all know me as Hades if they speak to me or of me at all, yet none hate this place as I do.”

“I felt ashamed that I couldn’t answer your questions. Now, for the first time, I’m curious and I’ve questions of my own.” He raised his gaze to Persephone. “You’re so beautiful, so alive and warm! How can you want to shut yourself away in this place? It’s a living death! Even if you want to stay, will you be allowed? Demeter is powerful.”

Persephone raised her chin. “I’m not a child. My mother must accept I’m ready for my own life now. You don’t compel me to stay. I choose it. I’m needed here.”

Kadmos came into the chamber with a tray and began clearing the table. “Lord,” he said to Hades, “one comes who would see you and the lady. She waits outside.”

“One who’s living?” Hades asked in surprise.

“Yes, Lord,” said Kadmos.

“Send her in, then,” said Hades, rising to his feet. “Bring some of Odin’s mead, and another cup.”

Kadmos left the chamber with his tray. Hades laid wood on the fire.

Kadmos returned with a bowl of purple grapes, another silver cup and the mead. He opened the door and stood back. A bent figure swathed in a cloak entered, followed closely by a wolf with amber eyes. The wolf moved to a place in front of the fire and lay down. A gnarled hand reached up and threw back the hood, revealing short straight grey hair.

“Hecate!” Persephone and Hades both greeted the old woman with respect. Hades took her cloak and offered her a chair. In this moment, the three of them were strangely akin, the strong-chested black-bearded man, the beautiful corn maiden and the lean old woman.

Hecate’s shrewd gaze moved from one to another. “So,” she said, “the children begin to grow up.” Persephone wanted to squirm under her bright, sharp gaze.

“Perhaps you can talk sense into the girl,” said Hades. “I’ve just been telling her she can’t stay in this place with me. She must return to her mother and the living world.”

“You—” Persephone began, furious.

Hecate interrupted. “You’ve been alone long enough,” she said to Hades. “All these souls look to you for guidance. It’s a hard kingship, Hades, but it’s your place and your duty. You may find joy in it, and wisdom, and you needn’t be exiled from warmth and companionship. Haven’t you longed for a companion? Does Persephone offend you in her looks? She seems beautiful enough to me!”

“No!” said Hades, and Persephone saw the skin above his beard redden in the firelight. “She’s too fine for this place of death!”

“You talk like a child!” said Hecate. “This is a threshold place, a place of transition. Haven’t you grasped that to speak of death, to be in death, is to be in life? Have you wasted all your time here in sulking? And do you think it’s your place to choose for this young woman? Might she not choose for herself? You underestimate her, perhaps.” She turned to Persephone. “What do you say for yourself?”

“I’m more than my looks!” said Persephone. “I want a life of my own. I want to learn. There’s power in this place and I want to understand it. I don’t ask to stay to be his plaything, his pretty toy!” She glared at Hades.

“You can’t stay!” roared Hades. “I won’t allow it!”

“You can’t stop me!” she returned. “Don’t tell me what to do! I’m not afraid of you and I’m not afraid of this place. I’ve learned more today than you have all your time here!”

Hecate’s dry laughter filled the chamber. “A worthy pair!” She said. “You may do much together. Now sit down, both of you, and listen to what I say.” She reached into some pocket in her clothing and brought out a round piece of fruit. It glowed with color, now red, now orange, now pink in the firelight. She laid it on the table and called out the door for Kadmos. In a moment, she returned with a board, a sharp knife and a bowl. She cut the fruit into four quarters so it opened like a flower, showing red fleshy seeds. She scored each quarter again, turned it over above the bowl and gave it a sharp tap. Seeds fell into the bowl with a soft sound. With the tip of the knife, she removed a few seeds buried in the rind and added them to the bowl.

Hecate set the bowl aside. “Now,” she said to Hades, “It’s time you assumed responsibility for your realm. You’re a king. The souls who stand on this threshold are your business. You’ll need all your wisdom, which at the moment is regrettably little. But you’ll learn. The dead themselves will tell you everything you need to know.”

Turning to Persephone, she continued, “We haven’t yet spoken of your mother. She’s suffering and everywhere the tale is told of your kidnap and rape.”

Persephone flushed. “What kidnap and rape? I chose to leave! I waited for Odin and the Wild Hunt!”

Hecate raised a hand to silence her. “I know, child. But you can’t expect your mother to accept that you wanted to leave her and chose this manner of doing it! As for rape, Hades’ reputation is deservedly black in that regard. Help is coming to Demeter, and I’ll go speak to her myself when I leave you, but I think she may not be so easy to soothe. She’ll fight for your return.”

“I’ll not be forced to go back!” But even in her defiance Persephone wondered if Demeter might not find a way to force her to go home after all. Home. It felt dear and familiar and she belonged there. She looked at Hades. He twisted the silver cup between his fingers, his gaze fixed on it. She could see the rumor of rape and kidnap rankled, yet she knew such thoughts had been in his mind in Odin’s stable. What, after all, was she thinking of? This gloomy, dark man was a stranger. Could she endure to live in the Land of the Dead, shut away from the green and living world? Yet the place spoke to her. She remembered the feel of Hades’ hand clasping hers as they entered the Underworld at the great gates. Troubled, she looked into Hecate’s eyes.

Hecate smiled. “The choice, Daughter, is yours. None can make it for you. Long ago the Norns decreed any who ate of the pomegranate in the Land of the Dead must forever be bound there. If you eat of these seeds not even Demeter can force you to leave. It is indeed time for you to find your own life.”

Persephone rose and stood before the fire. The wolf lay with its long muzzle on its forelegs, paying her no attention. Hecate and Hades were silent behind her. The fire burned to an orange glow, echoing the pomegranate’s color, the color of life in the Green World, the color of warmth and the sun. As she stood there, she became aware of peace. The choice was made. These quiet moments held a farewell, not a struggle for decision. She turned back to the table and moved to Hades’ side, laying a light hand on his shoulder.

“I’ll eat the seeds,” she said. Hecate passed the bowl over the table to Hades. He took it and spilled seeds into his broad palm. Persephone put her fingers into the bowl. The damp red seeds were smooth and heavy. Together they ate and the taste lay sweet and tart on Persephone’s tongue. Hades poured mead and they raised their cups to one another and drank.

“You’ve chosen well,” Hecate said to Persephone. “I’m proud of you. I’ll go now and speak with your mother.” She set her cup down, rose to her feet and gathered her cloak around her. The wolf came to her side. Persephone embraced the old woman and then stepped back beside Hades. Hecate looked up into his face. “It’s time now for learning and for joy. Your place in the world calls out for you.”

He bowed his head.

CHAPTER 2

RAPUNZEL

She glanced out the tower window and saw a stranger. She dropped her book and bolted to her feet, finding herself in the center of the room with her hand pressed to her drumming heart. She hadn’t seen a human being, except for her mother, in months. It was a shock. She felt annoyed by how much of a shock it was. Why did she feel so afraid, and dodge out of sight like a criminal? She was perfectly safe. She had nothing to be ashamed of. Still, she stayed out of view from outside the window.

When she looked out again, the stranger was gone.

When her mother came for her usual evening visit, Rapunzel didn’t mention the stranger.

The tower was light and airy. Rapunzel had her favorite cat for a companion, along with books, her needlework, and her paints. Carpets covered the floor and a velvet coverlet draped the bed. Her mother brought her food and wine. She wasn’t idle because her mother continued to teach her the old and secret ways.

The tower possessed neither doors nor steps. The only way in or out was to climb the golden ladder of Rapunzel’s hair.

The stranger came again and again, until he was no longer a stranger. He rode a white horse. She no longer hid when she saw him. He walked around the tower, looking for a way in. He looked up at her and she looked down at him. Neither spoke.

Now she entertained two visitors. Neither knew a thing about the other. The strange situation gave a welcome interest, a spice of tension to the sameness of Rapunzel’s life.

One day she heard the familiar call, “Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your golden hair!” spoken in an unfamiliar voice. He’d been watching. He’d seen and heard her mother. He’d found the key to the tower.

At the window, Rapunzel unpinned the long heavy plait of her hair, leaned out and wrapped it around a hook mortared into the wall. The plait fell down to the ground, a golden rope.

His name was Alexander. He was amazed by the tower room and her life there. He sat with her in the window seat, asking eager questions and never taking his eyes from the thick plait of hair, now coiled on the floor at her feet.

She’d never had a friend her own age before. She’d never talked with a man. Her only companion had been her mother. His questions were soon answered. Her life was small. First the cottage and garden of her childhood, and now the tower. The biggest part of her life, the secret ways of magic and power, she never considered revealing.

Her curiosity about him was even greater than his about her. He was a window on an unknown world, filled with people and far-away places. He came from a family of wealth and privilege. He was an experienced traveler. She drank in every detail with flattering attention.

Alexander changed. He spoke less. Every day he begged her to loosen her hair. She did, to please him, though it meant nearly an hour of work to comb out the heavy sheet, braid and pin it again. He ran his hands through it and kissed her like slow fire, and she forgot everything else for a time.

Rapunzel’s mother taught her about the power of the natural world. She learned the names of rain. She learned to master wind and read the subtle language of grass, herb and flower. Yet Rapunzel looked out from her high tower windows into a world of nature and people she was entirely removed from.

“What’s the use of all this learning? What’s the point if I spend my life locked in this tower? I want to be free!”

“The world is big and it’s not safe for you.” Her mother closed her lips and turned away. Rapunzel, weeping with rage and frustration, wound her hair around the hook outside the window and threw bitter words at her mother as she climbed down and walked away. The next day she came again, stoic, patient and unyielding, as though nothing had happened. Rapunzel smoldered.

Alexander called her his princess and kissed her mouth while he wrapped her hair around his hands. She was his secret joy, waiting for him in her tower. One day he’d set her free. They’d marry and she’d bear him many golden-haired sons. But for now, she remained his private joy, his cherished possession, safe in her velvet-lined stone casket.

Her mother and her lover talked and Rapunzel listened. After all, what could she share with them? What did she know? What could she learn, apart from what they taught her?

One night, while Alexander lay sleeping next to her, she thought, my hair gives them both freedom to come and go as they will. Why shouldn’t it give me freedom?’

The next morning Rapunzel stood by the window in the sun. She gathered up her hair, strand by strand, combing it smooth and plaiting it into its usual thick, heavy rope. She took a pair of heavy shears and cut off the plait.

She felt light and free. She turned around at the window, feeling sunlight on her bare skin. She washed and dressed, tidied the room and bed, and wrapped the rope of hair around the hook for the last time. She climbed down and walked away from the tower.

DEMETER

Demeter woke as early sun poured in through the window. Gale and storm the night before had left the air fresh and still. She’d gone to sleep thinking of wheat rippling and bending like golden fur in the wind. The cottage was quiet. Persephone still slept or perhaps was out with the horses. Demeter made her morning toilet. After she set the table with fruit, bread and honey and heated water, she knocked on Persephone’s closed door. She heard no answer. She opened it and found the bed made, the room tidy.

Outside, birds made a great noise as they began their morning activity in trees surrounding the cottage. Familiar barn smells embraced her and horses whickered in greeting as she slid the heavy door open. Persephone wasn’t there. She reassured the horses she’d be with them soon. Demeter walked here and there, visiting Persephone’s favorite places. At last, she walked through the trees and onto the bare hillside. She saw no sign of Persephone.

She returned to the house, troubled now. For her own comfort rather than any need, she ran a soft brush over the horses’ coats and tidied their coarse-haired manes and tails. She turned them out, forking hay into a pile against the barn wall. With fork and wheelbarrow, she cleaned stalls and put down fresh straw. She refilled water buckets at the pump and checked the outside trough, skimming wind-borne debris from water’s surface. While she worked, she listened for Persephone’s return. Leaving the barn cats crouched like the spokes of a wheel around their dish, Demeter returned to the house and put away breakfast, uneaten. She made herself tea and took it to an old chair of woven willow outside the door in the morning sun. She sat and waited for Persephone.

The sun rose to its zenith and then sank. Persephone didn’t come. Demeter did no work that day. In the evening, she made a bright fire for company and wrapped herself in a shawl of grey and purple. Hours passed and she sat waiting.

At dawn, she searched Persephone’s room. Nothing seemed to be missing except her cloak and a pair of sturdy leather boots. All her finery hung in the wardrobe.

As she let herself out of the cottage to go to the barn, she found a raven perched on the back of the willow chair. It flew to the ground and shifted into the shape of a woman dressed as a warrior in a leather tunic with a shield strapped to her body and a drinking horn at her belt. Her face looked hard and proud.

“I come from my father, Odin, with word of Persephone,” she said. “She was taken by the Wild Hunt and left Valhalla this morning in the company of Hades. Odin bids you to wait for further news of her. She’s well and unharmed.” As she spoke the last words, her form shimmered and wavered. The raven flew up and over the tree tops with great strong sweeps of its wings and disappeared.

Demeter took one of the horses and rode out into the world. She sent messages demanding aid and justice to Odin. She told everyone she met that her darling, her treasure, her innocent Persephone had been kidnapped and raped, spirited away by Hades. Persephone was much loved, and people heard the story with horror and grief. At last, exhausted and hungry, Demeter returned home late in the night. She cared for the horse but did nothing to ease herself. She built up the fire and sat wrapped in her cloak in her chair. The night passed. Demeter waited. Underneath the waiting, anger and grief swelled, pressing against her belly and chest, but Demeter kept herself still and silent. Soon, she knew, news would come.

Late in the evening of the third day, she heard a knock on the door, and without waiting for answer a bent old woman entered. At her heels stalked a large wolf with amber eyes. It lay down on the rug before the fire. Hecate threw back her hood and her eyes were like embers in the dim fire-lit room.

“I come with news of Persephone. She’s well and safe. Come, Demeter. Set the table and we’ll sup together while I tell you of her.”

They sat together, Hecate, Queen of Crossroads, Mistress of the Dark Moon, older than Zeus and all his family, and the Corn Mother, vigorous, generous bodied, abundance in every curve of hip and breast, hair thick and faded from the color of ripe corn to wheat. They drank barley water and ate bread and honey, olives and cheese. As they ate, Hecate told Demeter of the Wild Hunt, Persephone’s night at Valhalla and her journey to the Underworld with Hades.

Demeter stood up. Her cup tipped over. “The Land of the Dead? He took her to the Land of the Dead? My girl is a prisoner—with him—there?”

“Sit down and listen to me! He didn’t take her against her will, far from it! She insisted!”

“Oh yes,” Demeter sneered, “We all know what a gentleman Hades is! Far be it from him to coerce a young and innocent girl!”

“Demeter, listen to me! Persephone is ready for a life of her own. It’s time for you to let her go. She deliberately met the Wild Hunt and she’s chosen her path ever since. As for Hades, her courage and curiosity shame him. I’ve never seen him so subdued. Make no mistake, Persephone has the power to hold her own with him!”

“Very well. She’s had her little adventure. Now she must come home. She can’t stay in that place! My beautiful, bright girl in the Land of the Dead? I won’t bear it! I’ll find Zeus. I’ll demand her return.”

Hecate reached into her robe, drew out the empty rind of a glowing pomegranate and put it on the table between them.

The fire burned on the hearth, sap bubbling. Demeter fixed her eyes on the pomegranate and her face fell into lines of age and weariness.

“Surely the law can’t hold if he tricked her into eating this?” she said in a low voice.

“It wasn’t a trick,” said Hecate. “I took it to her myself. I told her the law. She chose to eat of it, knowing it would bind her to the Land of the Dead.”

“You took it to her. You took it to her?”

“Yes.”

Demeter rose to her feet. She picked up her shawl and draped it over her shoulders. She sat with her back to Hecate and stared into the fire, her hands resting in her lap.

Hecate sighed. She stood, pulling the hood of the cloak up over her face, and became an old woman, slightly bent, moving with weary strength to the door of the cottage. The wolf came to her side. She opened the door and stepped out into the night, closing the door behind her.

Nothing could prevent Demeter from caring for the horses, and for their sake she rose each morning, clothed herself and went to the barn. These morning tasks were all that marked the passing time. She wasn’t interested in food and took a mouthful of cheese or bread when she remembered. She longed for sleep and often dozed off in front of the fire, but when she lay in her bed she couldn’t rest. Sometimes in the night she opened the door to Persephone’s room and looked in it. If only she could discover the right way to open the door, Persephone would be there in her bed. Standing in the doorway, the room silent and lifeless before her, Demeter thought, Is it real? Is she gone? My sweet child, my girl—can she really be gone?

If Persephone was gone, was she still Persephone’s mother? If not Persephone’s mother, who was she? What was she? There seemed no point to anything. Demeter no longer recognized her life.

One night she heard another knock at the door. Demeter rose to her feet, determined to keep Hecate out. She flung open the door but a woman of her own age stood there in well-made but plain dress. She carried an air of power but her face was ravaged with grief. Demeter stepped aside and the strange woman entered. She bowed before Demeter, not as a servant but as a peer. “Lady,” she said in a colorless voice, “I’m Elizabeth. I’ve heard of your trouble.”

Demeter put a hand to her breast. “Do you bring news of Persephone?” she demanded.

“No,” said the other. “No news of your lost daughter—or of mine.” Her pain filled the room. She stood there with her eyes on the floor.

Demeter’s anger lay down. This woman understood her suffering. “Come,” she said. “Sit with me by the fire. I can give you tea. I’ve no comfort to offer but perhaps it would ease you to tell your story.”

Together they built up the fire and heated water. With the pot between them and cups on the table, they sat down together. Each looked into the fire. For a time, they were silent and then the stranger began to speak.

“A life holds many seasons of waxing and waning, even a lonely life, as mine has been. It’s hard to be outcast because of the color of your soul, but no matter. This is not a story of exile, but of another sort of loss…and gain.

I lived for a time in a little stone house in a gentle countryside. At the back of the house was a walled garden where I spent many hours tending the roots of my life. One other house stood nearby, inhabited by a man and wife. None came near me, of course, except for a few driven to my door in the darkest hour of night for some overwhelming need. We won’t speak of that. None came in the daylight hours with open face and outstretched hand to mingle their touch with mine in scented herbs, share the textures of life, or laugh.

A window of the neighbors’ house overlooked my garden. I often saw the young wife there. She appeared idle and pale and they’d no garden, made no home against the earth. My cats were my constant companions, but I never saw any creature next door but the man and his wife. Candlelight glowed dim in the nighttime windows and her face looked out nearly every day. I pretended not to see her and never exchanged a look or a word with either of them. They were afraid of me and kept a safe distance.

My garden grew happily, for I know the secrets of sowing and harvesting with moons, tides and seasons. One morning when dew lay heavy, I realized some other hand had picked the rapunzel greens. I thought this strange. Some person had climbed the wall in the night and risked who knew what fearful rumors to steal a common wild herb.

The next night I waited and watched and when the intruder let himself down into my garden I appeared before him. ‘How dare you come into my garden and steal my greens?’ Of course, he turned white and trembled and shied like a miserable, downtrodden horse, and begged my pardon. ‘My wife is expecting a child,’ he said, ‘and she saw your bed of rapunzel and felt she must taste it or die. She made a salad of the greens and found them so delicious she begged me for more.’

A child. His wife carried a child. That which my life had denied me was to be hers. Before the child was even born these two couldn’t take care of her by digging and planting a garden or making friends with the earth and gathering their own greens and many other herbs to make mother and child strong.

‘You may pick all the rapunzel your wife desires,’ I said, ‘but in exchange you’ll give me the child. I’ll raise it and love it like a mother. You needn’t fear.’ I looked into his eyes with all the force and power at my disposal. He was weak and afraid, conscious of his wrong. He didn’t fight. I knew he wouldn’t.

After the birth, I brought the child away. She was a beautiful, strong little girl, thanks in part to the goodness of the herbs from my garden, and I named her Rapunzel.

How shall I tell you, then, of years of joy? What do I say of laughter, play, life shared? Do you know hours in which sleep mingles, garden days, picnic days, walks in rain and snow? I taught her everything I know of the living earth. I taught her strength and wonder and how to read skies and seasons and hear the winds whispering.”

Demeter’s tears fell, hot and painful. Her hand trembled and she set her cup down.

“The years passed by and she became a woman. She had golden hair which I never suffered to be cut and my happiness was perfect.

But change came and stole away my happiness a drop at a time. As she grew up, she began to wonder about the wider world. She became restless and bored. She asked questions she’d never asked before.

A day came in which I decided I must shut her away.

It did it for her own good. She was so beautiful and so innocent. I couldn’t bear her to be shunned as I’d been. I couldn’t bear her to be spoiled or used or broken. I wanted to keep her safe from hurt and harm. I shut her in a tall stone tower I’d built nearby. The tower contained no ladder, steps or door, and she lived in a room at the top. Her room was filled with light and air and every luxury I could provide. Outside a window was an iron hook mortared into the stone wall and every day when I visited her I stood below the window and called up to her, ‘Rapunzel! Rapunzel! Let down your golden hair!’ She unbound her braid, twisted it around the hook and let it fall down the tower wall. I grasped it and climbed the thick, shining rope until I was with her again.

I thought I’d found a way to keep her safe forever. Every day I visited her so she wouldn’t feel alone. Sometimes she seemed quiet or cross, but I took no notice. Over the years I’d continued to teach her and her power grew at least as great as mine, though she lacked the experience to master it.

One day at the base of the tower I found her braid, shorn from her head and curled up like something dead, and I knew she was gone. The rope of hair felt lifeless in my hands. I entered the tower for the first time without the golden ladder I’d used with such love and pleasure, and my power felt like black and bitter wings. The empty room mocked me. She’d flown away and been lost in the harsh world. I was alone again, I sat grieving while hours passed. At dusk, I heard a voice below.

‘Rapunzel! Rapunzel! Let down your golden hair!’

I’d never felt such terrible anger. I wound the plait of hair about the hook and kept out of sight. He came up as though well accustomed to such a ladder. As his face rose above the window sill, I loosened the plait, summoning every power I knew for hate and harm, and hurled it out the window at him. He fell backward from the tower with a scream of terror and surprise. He landed in a thicket of thorns and thrashed, screaming with pain and bleeding in a dozen places. I was glad. I felt no mercy.

What I most longed for, to love and be loved by a child, broke me.”

Her rough sobs were like retching and she hid her face in her hands.

“I descended from the tower, and I ran,” she said. “I ran from what I’d done but I can’t run fast enough to get away from myself. I’ve betrayed my craft, misused my power, killed a human being, and she’s …she’s gone. My girl is gone!”

Demeter clenched her hands into fists and they wept together, two strangers with a single rage and a single grief.

Demeter rose from a sleepless handful of hours after Elizabeth went out into the night to continue her search for Rapunzel. Her face felt hot, her throat raw and her eyes swollen. She rinsed her face with water from the rain barrel in the cool morning air. It cleared her head.

She made tea, sitting in the willow chair outside the door in the sun to drink it and think of Rapunzel and her mother. At last, she tipped the dregs of the tea onto the ground next to a clump of creamy puffball mushrooms and went back inside.

She opened every window in the cottage except Persephone’s window. The door to that room stayed shut. She gathered every piece of bedding, her neglected clothing, curtains, dishcloths and table linens, and did an enormous wash, draping it to dry over lavender and rosemary bushes when the line became full. She took rugs outside and beat them until dust flew. She cleaned ashes out of the fireplace and brushed and scrubbed the hearth. As day sank into evening she brought in the laundry, made her bed and folded and hung everything else. The linen smelled of the sun and garden. She lay down exhausted in her fresh bed and slept.

After breakfast the next morning, she swept the floor with a dampened broom and then scrubbed it on her hands and knees until her back ached and her hands were chapped. She scrubbed the table, kitchen shelves and counter, noticing the nearly empty grain and flour bins and depleted tea herbs in their jars. She cleaned out the pantry and stirred and watered the compost pile. She washed days of dirty dishes and scrubbed the kettle and teapot until they shone. She cleaned lamps and chimneys, trimmed wicks and filled them. She didn’t pause to eat, drink or rest, but all the time she remembered Elizabeth’s suffering face and what she’d done in her anger and grief. By the end of the day the cottage was shining. Demeter felt bone weary and her anger was worn out. Once again, she slept until birdsong.

In the following days, she slept a great deal. Her weariness refused to be assuaged, no matter how many hours she lay in bed. Without the burning coal of anger in her belly she felt flat and diminished. She went about her tasks, noting without much interest the horses were at the end of the hay and their grain stores ran low. She washed and fed her heavy, joyless body and put one foot in front of the other, but she saw no point to it.

PERSEPHONE

Persephone and Hades explored the Underworld together. They collected the story of every soul they met. When the tale was told from beginning to end, they asked each soul what they wanted to do next. Some could answer but many could not, having so seldom possessed the power to choose. They needed time to consider. There was plenty of time, and Hades and Persephone bade them take it and come back when they could answer.

The Underworld transformed from chaos and fear to quiet order. A deep contemplative silence replaced uneasiness. Word spread. The life of every person, no matter how humble, how long or short, was a unique story to be told and heard and then the question, “What do you want to do now?”

Some asked to be released back into the Green World so their spirits could mingle with field and forest, animals, rain, stars and sunlight. Some wished for another life, a chance to make different choices. Some chose to stay in the Underworld for a time, and among these were many skilled craftsman and husbandmen, including the two antagonistic branches of the dwarf family. The Dvorgs called all places underground home and in some cases hardly noticed their deaths. The Dwarves, more accustomed to life above ground, possessed all the skill of their more traditional brothers. Hades granted form to those who wished it and the Underworld gradually became a place of shadowed beauty. The Dwarves and Dvorgs forgot their differences and worked together, hollowing and shaping rock, freeing hidden water and veins of jewels like underground galaxies.

Workmen enlarged the cave where the hot spring bubbled into a kind of bathhouse with a pool for soaking and washing and cold water piped in to splash in its own basin.

The dead who’d loved flocks and beasts and worked farms and fields were sent to the Green World to enlarge the barn where Hades housed his stallion so goats, pigs, sheep and chickens could be accommodated. Gardeners tilled and planted. Craftsmen built furniture. Women spun wool and wove.

Teachers came. Odin and the Valkyries visited and the old one-eyed man embraced Hades like a son. He brought as a gift a wolf pup with green eyes. Hel came from her boarding house on the northern sea, a threshold place like Hades where certain souls rested between one life and another. Hecate visited often.

Persephone and Hades learned and grew together. They gave of the Underworld’s abundance to all who came, according to his or her wants or needs. Odin and Hel received quantities of food and wine for their tables, and Odin bargained shrewdly with the dwarven folk for marbles made of bloodstone, jasper and flint. Hel accepted woven and dyed wool blankets. Her boarding house was in a cold country.

Baubo came one day to Persephone. Persephone had heard of Baubo the sacred trickster, Baubo the clown, and found a stout old woman with thin curls of grey decorating her pink scalp. She was round in shape, double chinned, and her face seemed made to smile. She possessed none of Hecate’s power and dignity. The care of children and infants was her responsibility and she came to instruct Persephone about their special needs in Hades, as these souls were unable to speak and choose for themselves. Persephone had given some thought already to these, so they soon took care of their business and Baubo felt confident the young woman understood what needed to be done.

Persephone offered refreshment and showed Baubo into a chamber set aside for her private use. Here burned a bright fire, flowers decorated the table, and comfortable chairs and thick woven rugs softened the stone room. A vein of black crystal was exposed in one wall. The rock around the crystals was carefully chipped away, and they were polished until they glittered. Frona brought tea, along with a round of creamy goat cheese, olives and bread.

“Now, my daughter, I also come to you as a mother and a counselor,” said Baubo. “How is it with you, Persephone?”

Persephone sat back in her chair and fixed her eyes on the fire. “I’m ashamed to tell you what’s in my heart,” she said. “I’ve found what I was searching for, and yet…”

“You left the Green World for the World of the Dead, child,” said Baubo. “Of course, you miss your home.”

“I dream of the barn,” said Persephone. “It’s early morning and the horses are stirring. I walk in and smell the way it used to be. Cats press against my ankles. Horses nicker. Sun comes in, so golden, so bright, and everywhere color and texture and life!” Her voice broke. “And then I wake and I’m in my bed. There’s much to do, much to learn, but nowhere is there touch, warm flesh, pulse. There’s no sunrise.” She turned and looked a Baubo. “The dead tell me stories of famine and suffering in the world. Why are people starving?”

“Yes, there’s famine in the land,” said Baubo. “Many die. Your mother has lost her joy in her work. Hecate visited her and tried to help, but Demeter can’t accept your absence. I’ll go to her soon and see what I can do, but this isn’t your fault. Children grow up and go into the world to seek their own lives. You were right to do so.”

Persephone looked into the fire again and tears fell down her cheeks. “I was cruel,” she said in a low voice. “I felt so trapped, so smothered before the Wild Hunt. But now … now I miss her so much, Baubo! But I ate the pomegranate seeds. I don’t regret it, but I can’t go back now and she’ll never come here. She’s lost to me.”

Baubo smiled. “Daughter, you’ll learn life isn’t all one thing or another. The story is not yet all told. It’s too soon to say you’ll never see her again.”

Persephone avoided Baubo’s eyes.

“Your feelings about your mother are not the only weight in your heart.”

Persephone wiped her cheeks with her hand. She shook her head but didn’t speak.

Baubo poured herself tea and sat back in her chair. She too gazed into the fire. “Here’s an old story that hasn’t yet taken place,” she said.

“Once upon a time not yet come and long ago, there lived a young man named Richard who committed the worst crime against a woman possible. He appeared before the court to receive justice. The judge was a woman. She sentenced the young man to discover the answer to the riddle, ‘What does a woman desire most?’ If he didn’t return in exactly one year with the correct answer, he’d forfeit his freedom.

Richard was astonished at the leniency of the sentence and felt he’d escaped punishment very well. As he made his way out of town, he saw an attractive young woman. He approached her with his best manners and most seductive smile.

‘Excuse me,’ he said, ’can you tell me what a woman desires most?’

She, in her turn, smiled coquettishly back, swaying her skirts and glancing up at him from under her eyelashes. ‘Of course,’ she said. ‘What a woman desires most is a lover!’

It was hot in the street. Richard wiped his forehead as he walked on.

A while later he saw a woman with a babe in her arms and two young children at her skirts. She looked tired and disheveled.

Again, he approached, courteous and friendly. ‘Excuse me, madam,’ he said, ‘could you tell me what a woman desires most?’

She hardly looked at him. ‘Rest,’ she said without hesitation. ‘What a woman desires most is rest and peace.’

As Richard reached the outskirts of town, he spied an old crone leaning on a stick. People passed her with some impatience, as her slow gait obstructed the foot traffic.

He fell into step beside her. ‘Excuse me,’ he said, raising his voice in case she didn’t hear well. ‘Can you tell me what a woman desires most?’

The old woman grunted. He noticed she didn’t smell good.

‘Health,’ the old woman wheezed, without looking up. ‘What a woman desires most is good health.’

Now Richard began to feel less confident about his task. Three women had given three different answers to this riddle. What if every woman gave a different answer? He decided to buy a notebook to keep track of the answers.

So, Richard went into the world with his notebook and his riddle. He talked to women of all ages and in all conditions. He asked his question of rich women and poor women, women living in towns and women working in fields, and every woman gave a different answer. He soon filled up the first notebook and bought a second, and then a third.

In this way, the year passed and the last day found him back in the town from which he’d started. Tomorrow he must to return to the court with the correct answer — or give up his freedom forever. He sat on a low stone wall with his head in his hands. How could such a simple question be answered differently by every woman?

In the midst of his despair, he heard a voice beside him.

‘Are you in trouble? Can I help you?’

Richard looked up. The ugliest woman he’d ever seen stood next to him, and by now he considered himself something of an authority on women! Her body was twisted and crooked. Her eyes were different sizes, small and dull, the color of mud. Her humped nose looked off center. Her mouth was too large, lips loose and flabby, and her discolored teeth leaned every which way. Her hair hung in lank rattails. She was hideous.

‘Tomorrow I’m to lose my freedom forever,’ he said, ‘unless I answer a riddle.’

The ugly woman gave him a look of polite inquiry.

‘I thought it would be so easy,’ said Richard. ‘I…I did something wrong and was sentenced to find the answer to a riddle. The judge gave me a year. Today is the last day of the year and I’ve filled three notebooks with answers to the riddle, but not one answer is the same as any other.’

‘What’s the riddle?’ asked the woman.

‘What does a woman most desire?’ Richard said.

‘Oh, that’s easy!’ said the ugly woman. ‘I know the answer. I’ll tell you, but you must do something for me in return.’

‘You know the answer?’ Richard asked in disbelief. ‘Are you sure you know the correct answer?’

‘Absolutely,’ she said with great confidence, and he believed her.

‘I’ll do anything if you’ll give me the answer,’ he said, hardly daring to hope. ‘Anything is better than losing my freedom.’

‘Ah, don’t promise so quickly,’ said the ugly young woman. ‘What you must do is…marry me.’

He stared at her.

‘Marry…you?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘I’ll tell you the answer to the riddle. You’ll go to court and finish your business and then meet me and we’ll be married. I know an inn, not far from here, where we can spend the night together. My name is Rapunzel, by the way.’

Richard hesitated. How could he bear to marry this hideous woman, promise to spend the rest of his life with her? But if he didn’t…if he didn’t he’d spend the rest of his life locked up. Better to be married to this ugly woman and free.

‘Agreed,’ he said. They shook hands on it. Her hand felt clammy.

‘What a woman desires most,’ she said, looking him in the eye, ‘is to stand within her own power.’

The young man thought for a moment. ‘Her own power,’ he said to himself, ‘her own power.’ He remembered his crime and realized he’d taken away a woman’s power, and felt ashamed. He thought of all the answers in the notebooks. Each answer fit into this answer. Each answer was different because each woman was different. This was the correct answer!

‘Thank you,’ he said to Rapunzel, and meant it from the bottom of his heart.

The next day Richard presented himself before the court. The judge was waiting for him.

‘Have you discovered the answer to the riddle: What does a woman desire most?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ he replied. He straightened his shoulders. ‘What a woman desires most is…to stand in her own power. And,’ he reddened, ‘and I’m truly sorry for what I did.’

‘Very good,’ said the judge. ‘That’s the right answer. Dismissed!’

Richard, true to his word (so you see he had learned something in his year with the riddle in his mouth), met Rapunzel and they were married.

They arrived at the inn and Rapunzel wanted some time alone to wash and make herself ready. Richard, rather sadly, went into the bar for a drink.

He bought a drink, and then another, and then another, making each last as long as possible. At last, the barman asked him to leave so he could close for the night.

Richard climbed the stairs to the room where he knew Rapunzel waited. He walked down the hall. He turned the knob and walked into the room. Candles and lamps were out and the window opened to admit a sweet evening breeze. Rapunzel, mercifully hidden from view in the dark, appeared a vague shape in the bed.

Richard took off one piece of clothing at a time, beginning with his boots. All the while he remembered the way Rapunzel’s skin had looked — like the belly of a dead fish. At last, he stood naked. He made his way to the bed and gingerly inserted himself into it, trying to stay as close to the edge as possible.

‘Aren’t you going to touch me?’ Rapunzel inquired.

He must! He knew he must. He reached forward, shrinking at the same time, and encountered…well, it didn’t feel like the skin on the belly of a dead fish! It felt warm and smooth and rounded and smelled wonderful! He moved closer and took her in his arms. He kissed her. Her lips were delicious!

He leapt out of bed and lit a lamp. By its light he saw the most beautiful woman he’d ever seen! And after a year with the riddle in his mouth he thought himself something of an authority by now on women! She had a cap of short golden hair.

‘Who are you?’ he demanded. ‘What is this?’

‘I’m your wife,’ said she, sitting up and letting the sheet fall. ‘I, uh…did something wrong and my punishment was to take on the appearance I had when you met me until a young man agreed to marry me. When you did so the sentence lifted. But, there’s more…’

‘What more?’ he inquired cautiously.

‘Well, now you must make a choice. You must choose whether I’ll be as you see me now by day and ugly by night or beautiful by night and ugly by day.’ She spoke quickly and angrily.

Thinking of the night ahead, and not noticing her irritation, he said, ‘Ugly by day and beautiful by night!’

‘So,’ said Rapunzel, ‘during the day, everywhere we go, people will laugh and jeer. Young children will run away in fright.”

‘Oh,’ he said, picturing it. ‘Well then, ugly by night and beautiful by day!’

‘Fine,’ she said. ‘Every night for as long as we live, you’ll get into bed with the woman you met on the street.”

The young man thought. What best to choose? ‘Wait,’ he said. ‘Wait a minute. This choice shouldn’t be mine. You’ll have to bear with it more than I. I’ve learned what a woman desires most is to stand in her own power. I think this choice should be yours, and I’ll abide by it.’

She looked surprised, gave him a smile and became even more beautiful, if possible, than before. ‘A good answer,’ she said slowly. ‘Then I choose to be beautiful by day and by night!’

And so it was.”