The Hanged Man: Part 6: Ostara (Entire)

In which you can read the whole thing without interruption ...

(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of The Hanged Man.)

Part 6: Ostara

(O-STAR-ah) Spring equinox; balance point between Yule and summer solstice. Increasing fertility and creativity.

The Card: The High Priestess

Female power and wisdom

CHAPTER 18

MIRMIR

“The firsst to arrive iss Baba Yaga. She doesn’t know she’s arrived, for she sleeps, lying flat on her back with her chin and nose curving over her mouth, snoring. Her bed is rather greasy, as there hasn’t lately been a skivvy to wash her laundry. The bed stands in a room and the room is in a house on scaly chicken legs and the chicken legs have done the work of travel and are quite happy to reach the end of the journey. The legs stand in the sun, looking peaceful, slightly cocked at first one knee and then the other, like a horse. The house’s eyelids are closed and a long thin string of sticky saliva falls from the lock on the front door, which is made of a bony snout with sharp teeth. Baba Yaga has tasks to do and preparations to make, but for now she sleeps.”

“Sleep ends abruptly, and with it, peace. Baba Yaga wakes with a strangled snore, springs out of bed with fire on her tongue, throws open a window, making the human finger bone catch rattle, and lets a magnificent flow of cursing and shrieking come up from the bottom of her iron-tipped dirty feet.”

“Ugh,” said the Hanged Man.

VASILISA

Vasilisa and her companions, sitting in a quiet group near the edge of a sun-filled glade a respectful distance from the dozing chicken legs, jumped in surprise when Baba Yaga appeared at the window, as did the chicken legs, executing a comical hop as they momentarily lost their balance.

Nephthys recovered herself first. She stood up, facing the shrieking, gesticulating figure in the window.

“We didn’t wake you up,” she called. “We were quiet. We were invited to the party, and we’ve come!”

Vasilisa envied Nephthys’s assurance. Her previous experience gave her no confidence in dealing with Baba Yaga. She groped in her apron pocket with two fingers and felt the doll her mother had given her. The doll had seen her through her first encounter with the Mother of Witches, and she’d been alone then. Now she was with friends, and perhaps someone who offered more than friendship would be here as well. Rumpelstiltskin had told her and Jenny initiation was a choice, an invitation to growth and power, but Vasilisa knew both would come at a price if Baba Yaga took a hand in things, and she feared the price.

In fact, her initial encounter with Baba Yaga had not been her first brush with deep magic. It seemed strange to her that an impoverished peasant girl of no importance and no family should encounter anyone with great power, yet she had. Perhaps the doll her mother made her attracted magical energy. Power was a fearful thing, and she didn’t want to attract it, but the doll was all she had left of her dead mother and she couldn’t lay it aside. In an effort to remain unobtrusive and unworthy of either punishment or notice, she’d worked hard to be kind and accommodating since childhood.

Even so, magic and power found her, and here she was, yet again, in proximity to Baba Yaga.

She lifted her chin. She would see it through. She would not be cowed. If her hopes were realized, she would step across the threshold of this initiation into a new life — the life of a woman. She would hold fast to that.

Baba Yaga withdrew inside the house, but they could hear her muttering and cursing as she moved about, slamming doors and cupboards and knocking objects over. They heard a smash, as if a plate had been hurled against a wall. The front door opened and Baba Yaga appeared and stomped down the stairs to the ground. Without so much as glancing at the group watching her with varying degrees of amusement, interest and horror, she bent over a huge greasy black cauldron, stirring the unseen depths with her bony arm. The stirring released a stench that reached the circle on the grass. Baba Yaga emerged from inside the cauldron with a long bone gripped tightly in her hand. Grumpily, she stumped to a flat piece of ground well away from the trees. She used the bone as a stick and drew a large circle in the earth.

“Fire pit,” she said briefly, glaring. “You,” her needle-like gaze on Jenny, “and you,” this to Vasilisa, “dig and lay stones.” Her eyes moved to Rose Red. “You gather wood.” They looked back at her in fascination for a moment, and then she opened her mouth and roared, “Do it now, brats!”

They did. Baba Yaga completely ignored Rumpelstiltskin, but he didn’t appear to take this to heart. As Vasilisa bent her back over her shovel, she watched him go to a large piece of rock near the edge of the woods, study it, tap it with his mallet, take out his chisel and split it into thin slabs, perfect for lining the fire pit. He lent a hand with the digging, helped drag the pieces of rock to the pit and showed Jenny and Vasilisa how to fit them together as a lining, then went with Rose Red under the trees with a hatchet and saw. In an unbelievably short time, they’d made a fire pit and laid it with kindling, ready for lighting.

Meanwhile, Nephthys dragged her folded piece of cloth over to Baba Yaga’s cauldron and the child and crone bent their heads together over the contents.

The fire pit finished, Vasilisa returned to where Mary and Artemis sat. She tried to see what Baba Yaga and Nephthys busied themselves with. She suspected the knotted dragging cloth contained bones, and if so, she thought she might know what would come next.

Artemis’s attention was on something, and Vasilisa followed the direction of her interest. A rabbit moved slowly out into sunlight from the cool shadows under the nearby trees, hopping and pausing to feed in the leisurely manner of a rabbit without fear. It moved to and fro, nibbling busily, ears twitching as an insect or long green stem tickled. To Vasilisa’s surprise, the rabbit approached Mary as though it knew and trusted her. Tentatively, looking amazed, Mary reached out a hand and stroked its back. Its fur was a soft brown, warm with sun.

“Do you recognize him? He recognizes you!”

Vasilisa looked up, startled. A young man stood there, pushing straight black hair out of his eyes. His skin was olive and his eyes almond shaped. He grinned at Mary, cheeks bunching into firm rounds.

Careless of the rabbit, Mary sprang to her feet in one swift movement and flung her arms around him.

“Kunik! Kunik! I can’t believe it! What are you doing here?”

MARY

“Girl!” It was a shriek of impatience, as though the caller had been at it for some time.

Mary, released from Kunik’s embrace, turned and found Baba Yaga, standing with hands on hips, radiating contempt. Nephthys stood next to her, looking rather bored.

“Come here!”

Mary immediately obeyed, feeling dazed by the sudden and wholly unexpected appearance of Kunik, and greatly reluctant to approach the old hag. Baba Yaga watched her come with a beady eye. She tapped a sharpened tooth with an iron fingernail. Mary stood before her, looking at the ground so as to avoid the Baba’s fierce gaze and also in an effort to palliate the stench coming from her. Baba Yaga walked slowly around Mary and it seemed to the young woman her eyes saw through her clothing and skin into her very soul. The Baba came back in front of her, looked at Nephthys with a raised sarcastic eyebrow, and snorted magnificently through her nose, shooting out a virulent green blob of mucus.

“Show me your seeds, Seed-Bearer,” demanded Baba Yaga. In spite of the sneer in her voice, the title gave Mary courage. She raised her gaze to the Baba’s cold eyes and reached into her tunic for the seeds. Nephthys gestured towards the ground and Mary knelt next to Nephthys’s cloth and laid out her bundles and bags of seeds.

She unpacked the pouch of birch bark made so long ago in Janus House, lined with sealskin and holding carefully labeled twists of seeds. There were the pouches from Elizabeth and Demeter and the red silk bag from Anemone. There was the sandy bag from Nephthys. Mary laid out, one by one, every bundle and twist and pouch she’d collected on the road. When she had displayed them all, she stood again and looked silently at Baba Yaga.

“Hmmph,” said the Baba, pleased and yet not pleased. “Is that all?”

“Yes,” said Mary, feeling inadequate but too intimidated to defend herself.

“Hmmmmppphhh,” repeated the Baba, drawing out the sound nastily. “Very well. Go away.”

Mary retreated gladly, conscious of the Baba’s eyes on her all the way back to the group sitting in the sun. She took care to go slowly and keep her back straight.

Kunik sat in the circle with the others, looking quite comfortable and at ease. Mary remembered the shy boy she’d met on a winter day at the edge of the icy sea. She remembered the strange, heartbreaking story Kunik had told, the wonder and tenderness of his drumming, how he’d created picture and sound and movement with the instrument. But she couldn’t remember a rabbit. A rabbit at the edge of the winter sea?

She reached the group. Kunik was speaking.

“…and so, the white rabbit became a brown rabbit and when at last the burrow he’d found became unblocked, he went through and found himself back at home, in the place where he’d started, now a lovely, scented place with green grass, shy flowers and damp earth, and, best of all, other little brown rabbits.”

The little brown rabbit, nestled close to Kunik’s knee as he told the story, hopped over to Mary and crouched in front of her, looking up with dark eyes.

“Surrender!” she said. “It’s you? You’re real?”

The rabbit dropped his gaze and nibbled at a bit of clover between his front paws.

Mary looked at Kunik helplessly, not even knowing how to frame a question.

Kunik laughed. “Oh yes, he’s real.”

“I don’t understand,” Mary began, but the rest of her words were lost.

VASILISA

A rough track wound out of the trees across the clearing, and a brightly painted wooden cart drawn by a horse appeared. On the side of the cart the words, “Come and be welcome. Go and be free. Harm shall not enter.” were painted. At the reins lounged a lean man with dark hair and shirt sleeves rolled up over hard-looking forearms.

Two men on foot followed the cart, walking together in easy companionship.

“Artyom!” Vasilisa called, and ran to meet the shorter of the two men.

He looked just as she remembered, with his short sandy hair, his wide chest and the clothes he wore when hunting or traveling without the trappings of his royal birth and station. She noticed with pride he wore one of the linen shirts she’d embroidered for him. She wanted to throw herself into his arms the way Mary had greeted Kunik, but she was conscious of all the eyes upon them and Artyom’s position. He smiled warmly, but embraced her formally, kissing her on each cheek, and she endeavored to match his restraint.

Artyom’s walking companion was Radulf, an older man with thick grey-flecked hair, a short beard and deep-set eyes.

After a few minutes of jumbled introductions and excited talk, which Baba Yaga pointedly ignored, order was restored.

Vasilisa watched the cart driver move gracefully across the clearing to where Baba Yaga bent, muttering and clawing among piles of seeds and bones.

“Weeelll!” sneered the Baba, deigning to take notice.

“Good day to you, Grandmother,” he said respectfully, but his eyes gleamed with mischief.

The Baba glared at him, tapping a bony foot impatiently, huffing in an aggravated manner. Suddenly she stopped, strained briefly, and farted loudly.

“Oh, get out of my sight,” she snapped. “You’re far more trouble than you’re worth.”

He turned and walked back to the group of fascinated onlookers around the cart. Vasilisa could see him chuckling to himself. The horse, still in his traces, shifted his weight from one hind foot to another, cocked his tail and farted in echo of Baba Yaga, but with much better-smelling results. Nephthys, still with the Baba, giggled delightedly, and Vasilisa exchanged smiles with the others, but remained prudently silent.

Vasilisa and Rose Red helped lay food out on blankets while the others fetched water, unloaded the cart, and unharnessed the horse, who was called Gideon.

Rumpelstiltskin and Rose Red found wild strawberries. They were tiny, the size of the end of Vasilisa’s thumb, and tartly ripe. Artemis invited Baba Yaga and Nephthys to sit down and eat. Baba Yaga glared, snorted, and stomped up the stairs to her front door, which she slammed, making the chicken legs twitch. Nephthys, smiling to herself, skipped over and plopped herself down next to Mary. Kunik gave Surrender a mound of strawberries and evicted him from the middle of the circle of people.

They finished the meal with handfuls of strawberries. The cart driver, Dar, took a soft velvet cloth from an inside pocket and unwrapped a bone flute, banded with silver and decorated with gems. He polished it, though it looked to Vasilisa as though neither speck nor smudge marred it. He put the flute to his lips and began to play.

Next to her, Artyom lay back in the grass, hands folded over his stomach and eyes closed. Vasilisa feasted her eyes on him, the strong blade of his cheek with its gleam of blond stubble, his broad hands, a gold ring on the little finger of his left hand, and his dusty boots. He was there. Her fears about the initiation and the price Baba Yaga might exact for it drained away. With Artyom at her side, she could face a dozen Baba Yagas. And after initiation…well, she would learn to be the wife of a ruler. She would be worthy of him.

Theirs had been a strange courtship, mostly at a remove, with the Firebird as a go between. She would never forget the first day she’d seen Artyom in the market. His servant bought Vasilisa’s linen for Artyom’s shirts, but the linen was so fine he couldn’t find a seamstress, so the young ruler himself came to ask her to make the shirts.

They came from the same land of deep forest, though he was a ruler’s son and she a peasant. They shared a common language, and they shared the Firebird, the magical creature every child in their country knew stories about. The jeweled Firebird could lead you to your treasure, legend said. Vasilisa, imagining such a creature, embroidered Artyom’s shirts with a border of Firebirds in red silk thread, and like some hero out of the old stories, he’d brought the Firebird out of myth into reality and it became their courier.

At her first encounter with Baba Yaga, the old hag gave Vasilisa a human skull on a stick, a fearsome object that reduced her stepsisters and stepmother to piles of cinders while Vasilisa slept. At times it burned with a fiery light, and at other times it appeared to be nothing more than a rather battered old skull. This weird object made Vasilisa more nervous than the doll her mother had made. That at least had been a gift of love, a gift made out of her mother’s blood and tears. The skull was a different matter, yet Vasilisa found her reluctance to set it aside was greater than her reluctance to keep it with her. In an odd sort of way, it seemed to watch over her and guide her, like the doll. The skull could be deadly, however. She did not mourn her stepmother and stepsisters, who had done their best to destroy her, but she hadn’t wished them burned to cinders, either. No doubt it had been difficult to share husband and father with a daughter from a previous wife.

The skull and the Firebird demonstrated a strange affinity. The skull invariably lit in the Firebird’s presence. Noting this, Vasilisa impulsively loaned the grisly thing to Artyom the second and last time she’d seen him. Like the Firebird, the skull connected them is some deep way. It was an unlikely love token, but it was one of her two most powerful and valuable possessions.

It also assured she would see him again, at least once, to retrieve it.

After that second visit, they’d written nearly every day. Now, at last, they came together again to take part in this initiation, and the skull rested on Artyom’s discarded coat on the ground beside him.

Vasilisa leaned back on her elbows, closed her eyes, and felt the warm sun on her face. The taste of strawberries lingered in her mouth. Her stomach felt comfortably full. A strand of tough dried meat was trapped between two of her teeth. She felt it dreamily with her tongue, trying to dislodge it. The notes of the flute idled, leading her thoughts this way and that in the same way Surrender hopped slowly in the grass. The music moved, then paused. Moved one way, then another. Back tracked. Moved quickly for a few notes and then slowed down again.

Vasilisa realized the music had stopped. She lay next to Artyom in the warm grass, completely at ease. She thought perhaps she’d fallen asleep for a moment. No one spoke and a deep, easy feeling of relaxation settled on the circle. She felt alert but disinclined to move.

Rumpelstiltskin began to speak.

“She arrived in a world of people who didn’t recognize her. She arrived in a world that knew no word for her. She was named, but not by the world she was born into. She was of the world, her bones of the world’s clay. Water, root and leaf knew her and welcomed her. Insect, bird, reptile and furred creature took no more notice of her than of a crystal of frost, a dewdrop, a fallen petal.

But to the world of men, she was like the coming of a cataclysm.

She was named ‘gift of all,’ ‘all giving,’ ‘all gifted,’ ‘all endowed.’ She was named Pandora.

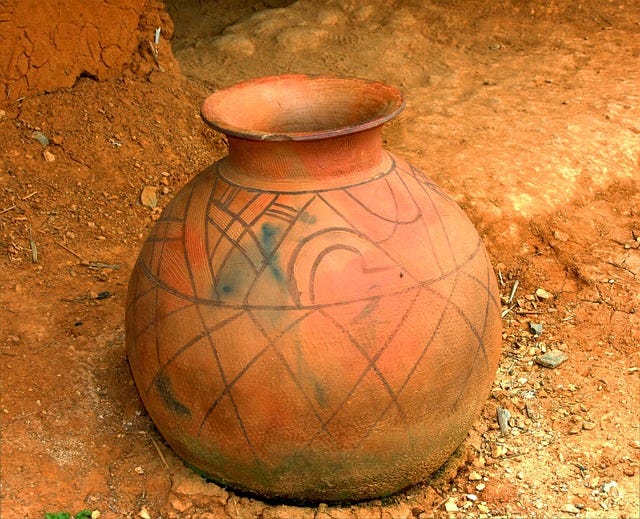

Her dowry was an unremarkable lidded clay vessel.

So much for the bones. Now what of the flesh?”

Rumpelstiltskin paused, looking around at the circle of faces.

“What is a woman?

A woman is a creature of malice and cunning. She has honey on her tongue and blackness in her heart. She’s a trickster, a twister, a snake. She’s a sharp knife buried in a man’s gut as she calls from his body the helpless moment of pleasure. She’s a seductress, a succubus who feeds on male essence. She’s a whore, a hag, a black cunt, a bitch. Her name is a lie, a cunning deceit, a twisted irony from the heart of Evil.

Plague and pestilence, pain, toil, sorrow and mischief were the gifts nesting in Pandora’s jar. Her jar was a prison, her treacherous hand the key. The only help, the only palliative to dark destruction that overcame mankind because of cursed Pandora remained fast in that prison, for she closed the lid too soon and locked away Hope, the last thing to emerge from the jar. Hope, that might provide a ray of light, a way forward, a glimpse of paradise lost. Hope, that fluttered with fragile wings around and around its dark cage and then lay crumpled, weightless and still in the bottom of the resealed jar.

Such was the first woman, Pandora, mother of all women, chalice of all evil in the world.”

After a pause, Rumpelstiltskin continued.

“A woman is a chthonic force, the spirit of Earth herself. She’s Gaia in human form. Within her move tides of fertility, creativity, cycles and seasons. She’s the cauldron of life and inexorable wisdom of death. She’s neither merciful nor cruel. She is.

Pandora, first woman, carried a jar. The jar contained everything needed to transform Earth into a world of infinite beauty, self-organizing and wise. In the jar were opportunity and choice. The jar contained life, neither good nor bad, but simply itself. When it was time, wind blew the jar over. Rain melted the lid’s seal. Freeze and thaw joined hands with snow and sun and the jar broke into fragments, like a hatchling’s egg. One thing remained among the shattered shards of Pandora’s jar. Hope lingered, grieving for the loss of how it had been, hoping for things to get better.

Such was Pandora, All Mother.”

“A woman is a question,” said Rumpelstiltskin. “A woman is one who sees with her nipples and speaks with her cunt and loves what’s real. A woman holds, heals, supports, renews life and cradles death. She strokes, stretches, urges on, licks, sucks, feeds and nurtures growth. A woman is source, fountainhead, cool dark well.

Pandora, she of all gifts, carried all blessings. Her jar served as an inexhaustible pantry. Freely, she gave her abundance, but a certain man wanted more. He wanted … more. Why should he not be the one to give … or withhold? Why did this creature called Pandora possess power and he didn’t?

He lifted the jar’s lid, meaning to capture all blessings and hold them fast until he decided how best to use them. Foolish man! The blessings slipped away and were forever lost. At the last moment, he clapped the lid back on the jar, keeping Hope safe. Hope. And the man said, ‘Didn’t I save the best thing?’ and ‘Wasn’t the greatest gift preserved by my quick thinking?’ in an effort to distract others from his act. And all agreed. Pandora was to blame. Pandora and her jar. Pandora and her tempting gifts. Naturally, men wanted the power to dispense such gifts.

No one discerned the two faces of Hope.

Such was Pandora, first woman.”

Again, Rumpelstiltskin paused.

“A woman is a tool, a chattel, an animal, a subnormal child. She must be kept ignorant and powerless. A woman is a pussy, a tit, a hole in which to find pleasure. A woman is a scapegoat and a satisfying splitting of skin under knuckles. A woman can be taught to cringe, to flinch, to obey. A woman can be adornment, servant and slave. A woman can be manipulated. A woman is weak. A woman is a piece of property. A woman is sly and curious and disrespectful. A woman is a stupid creature.

Pandora was ordered to carry the jar and keep it safe but to never look inside it. She arrived in the world of men, a place of ease and leisure and comfort, a place of full bellies, sleep, indolence, pleasure of all kinds, a place of paradise, in fact, and out of female weakness and curiosity she opened the jar and released the contents into the world. When she realized what she’d done, she slammed the lid back on the jar. The only thing left in it was Hope. Hope, the only anodyne to a world of misery created by Pandora’s disobedience.

Such was the nature of the first woman and all women who come from her bitter seed.”

“Bravo, maggot,” said Baba Yaga from behind Vasilisa, making her jump. “You saved the best for last. Women are tit and ass, empty hole and empty head. Useless, weak, puling creatures, women! Know nothing and want to know less than that!” She preened, sticking out her chest, bending a knee and standing hipshot in dreadful parody of female invitation. “I, on the other hand, I’m Storm Raiser! Ha! Lady of Beasts, they call me! Primal Mother! Hag! Crone! There’s power! Who was Pandora? Meddlesome wench! Poking her long nose where it wasn’t wanted! She destroyed Paradise accidentally. I’d do it on purpose!” She spat contemptuously on the grass inside the circle. Surrender bolted, making for the cover of trees in a flash of white tail.

“Ha!” said Baba Yaga, watching it go. “Rabbit stew! Not so good as child flesh, but still…” She walked away, toward her chicken-legged hovel.

The group behind her relaxed, returning their attention to Rumpelstiltskin.

“How do you know so much about Pandora?” Jenny asked the Dwarve.

“Because Pandora and a Dwarve named Jasper began it,” he said. His rugged face broke into a smile. “They became the first to join hands in the long line of dwarves and young women bound together by respect and love. Because of them, the tribes of women and Dwarves are each strengthened.”

“What did you mean about the ‘two faces of Hope’?” Vasilisa asked Rumpelstiltskin. Hope is a good thing, isn’t it? What’s the other face?”

Unexpectedly, Artemis answered. “Hope is essential, yes, but it’s not enough.”

“What else is there?” asked Artyom.

Nephthys jumped to her feet. “Hope is the last light to be extinguished, the honey in the mouth, the nice thing that forgives and forgives again its enemies!” Her childish voice recited the words. She slid a gold bracelet off her wrist and threw it into the air. As it fell, a silver shaft pierced its center and silver and gold dissolved into thick liquid and white fragments falling through the air. Nephthys reached out and caught the shattered remains, closing her fist around them. Her hand gleamed with viscous strings and drops.

Artemis was on her feet too, poised with her bow, bared arms strong and steady, having shot an arrow through the falling gold bracelet.

“Hope is the River Von, the slobber dripping from Fenrir’s jaws.” said Artemis. “Hope is the Challenger, the Warrior, insipid alone and indomitable combined. Hope is the tamed, the civilized, the captured, and the final abdication.”

Nephthys flung the contents of her hand into the center of the circle. A small pile of slippery wet teeth with sharp points fell in the grass.

“Fenrir was a monstrous wolf out of legend,” said Radulf unexpectedly. “Foam from his jaws formed the River Von, river of hope or expectation.” He picked up one of the teeth with something like reverence and examined it, eyes hooded and head bent.

“You’re saying hope must be combined with intention,” said Rose Red to Artemis. “You told me your bow means focused intention.”

Artemis put aside her bow and resumed her seat. “Well done, Daughter,” she said. “Hope is an invitation, an open doorway to change, but it’s weak and ineffective without intention and action. That paradox underpins Pandora’s story in all its versions. How useful is Hope? Is it different from plague, pestilence, and the rest? Is it blessing or is it abdication? Many people live wretched lives with hope in their mouths, but take no action to fulfill it.”

“Don’t give up your hope,” said Artemis to the circle. “But understand hope without action, hope without intention, is powerless.”

A shrieking high-pitched cackle of laughter, erupted into the sun-lit clearing. “Oh, but teacher, hope is such a pretty word,” jeered Baba Yaga, “so nectarous and winsome!” She squatted some distance away on an overturned barrel with her knees spread wide apart under her ragged skirt, displaying much more of herself than Vasilisa wanted to see or even think about. She held a half-gnawed bone in her hand.

Radulf, ignoring the interruption, left his examination of the tooth and looked across the circle at Rumpelstiltskin.

“Pandora is a woman’s story. Why did you tell it to us?” he indicated Artyom, Kunik and himself.

“Women are mothers to men,” Rumpelstiltskin replied. “Pandora is the hidden thing. Her business is secrets, things lost, things misleading. She’s shape hidden within shape. She’s greatest evil or greatest blessing, and her stories are hard stories of loss and truth. I told you her story because you’re here to be initiated into your own power, and woman or man, your power is incomplete without that which is hidden from you.”

Baba Yaga broke in again. She pointed at the skull next to Artyom with the bone. “I see you brought back my property, boy!” Artyom, avoiding all eyes and looking expressionless, nodded curtly. Baba Yaga turned her malicious gaze onto Vasalisa. “This one stole it one dark night, didn’t you, my little fledgling?”

“Yes, Grandmother,” said Vasalisa submissively, although Baba Yaga had in fact given the fiery skull to Vasalisa. It wasn’t fiery now, just a worn-looking human skull, rather sad in its fragility and age.

“Weeellll,” said Baba Yaga, drawing out the sound as her eyes traveled around the circle. The look on her face was both pleased and not pleased. “It sees secrets, never fear, but it won’t speak. Silent as the grave! Silent as the crypt! But I, on the other hand… “Her voice rose and she snapped her fingers with a sound like a bone breaking.

“Come and join us, Old Mother,” said Dar suddenly in a coaxing voice. The young women looked astonished, the men horrified. Artemis’s lips twitched and Rumpelstiltskin hid a smile in his beard. Dar moved over, practically into Artemis’s lap, and smiled seductively at Baba Yaga, patting the ground next to him in invitation. “I’ll let you play with my flute if you come,” he said, grinning at her like a boy. “I’ll let you look at my marbles.”

“It’ll be your last look, puppy! Soon they’ll be my marbles!” She stood for a moment, glaring, and then turned and clumped away, radiating contempt.

Dar grinned at Artemis, who pushed him away. “You can’t resist, can you?”

“Serve you right if she’d come and sat in your lap, you young devil,” said Rumpelstiltskin. “What’s this about marbles?”

“Next week is the spring marble championship,” said Dar. “She plays. So do I.”

“She does not!” said Rumpelstiltskin.

“She does,” Artemis assured him.

“Well, anyway, we got rid of her for the moment,” said Dar.

“She’ll be back,” said Artemis.

“Everything lost is found again,” said Nephthys suddenly.

“Yes,” said Rumpelstiltskin, returning his attention to the discussion at hand. “Thank you, Nephthys. We were talking about Pandora and the hidden thing.”

“What about private matters, information nobody needs to know?” asked Artyom. “Shouldn’t we have the power to reveal or conceal our own truths?”

“Certainly,” replied Rumpelstiltskin. “But in exercising that power we limit ourselves. We stay small to conceal a secret.”

Artyom shook his head slightly, biting a fingernail.

“But you told different versions of the Pandora story,” Jenny said to Rumpelstiltskin. “What is the truth? What does it mean, exactly?”

Shape within shape,” said Kunik promptly.

Nephthys said, “Truth is bone.”

“Seed is truth,” said Mary.

“Love and intuition?” asked Vasilisa.

“Truth is a fearful thing,” said Rose Red in a low voice, “shattered and sharp.”

“It’s elusive,” said Radulf with unexpected roughness. “It hides just out of sight, never showing itself, but letting you know you’ve failed to understand.”

“All wrong, poppets,” sneered Baba Yaga, who had returned unnoticed, making several people jump. “All wrong, my little pustules!” She flapped her skirt, unfolding a thick, eye watering smell of greasy fish, old blood and urine. She grasped her ragged tunic with both hands and pulled it apart, revealing a sagging, wrinkled potbelly the color of a dead fish. She caressed herself with her iron-tipped hands, cradling her own flesh in a grotesque mockery of a pregnant woman. She leered from one face to another, moving her hands slowly up to cup flaccid, drooping, sac-like breasts and then dropping them again to her obscene round abdomen.

“Truth is Death!”

“If truth is death, then you know very well truth is birth, too,” said Dar crossly. “If you claim the one, you must include the other.”

“Hhhhmmmph!” said Baba Yaga. “Maybe so, but this belly holds death and rot!” She opened her mouth wide, then wider, impossibly wide, so they could see grey sharpened teeth curving upwards into tusks. She blew out a breath, a fetid charnel house wind that clogged in their throats and made their eyes water. On and on it went, blowing over them, the smell coating their skin and hair and clothing.

Jenny retched helplessly. Rose Red swallowed thick saliva and willed herself not to gag.

Baba Yaga inhaled dramatically. “I’ll show you truth, my pretty little toads.” She cackled. “May it burn your eyes out! May it haunt you forever! I’ll show you! I’ll pry your innocent eyes open until they stretch and tear and bleed and pop out and roll on the ground in agony! Oh, yes!” She rubbed her hands together, chortling and rocking where she sat. “We’ll open jars and boxes and baskets and look behind screens aplenty, my little festering froggies! Old Baba will show you the Truth, never fear!”

She bounced to her feet. “But not now! Not yet! Now there’s work to be done!” Her voice rose into an unearthly shriek that made Vasilisa wince. Baba Yaga skipped forward, bent and picked up the skull Artyom had brought to the circle of story. She held it high over her head and the skull ignited into a fiery blaze that spilled out every orifice and crack in the bone. Vasilisa realized the sun would soon set.

“This needs a throne, a pedestal, a place from which to watch you miserable moppets! Plant a post for it, lackbrains! Build me a fence, nestlings! Find your bones and build me a scaffold! Raise gallows, a rack, a fortress, a prison! Build me a gate, a threshold, a bridge to Hell! Build me an arena in which to die!” she went off into mad laughter, the skull glaring in her upraised hand.

The group looked at her in fearful fascination and then Nephthys jumped to her feet and skipped past Baba Yaga to where her dragging cloth lay. Mary, remembering her seeds lying there with the bones, followed her, and then the others. They stood uncertainly around the jumble of bones and neatly laid out rows of seeds. Nephthys carefully set the seeds aside and spread out the bones. Some were stained and yellowed with cracks and chips, and others were white and hard looking. On the ground lay a careless pile of shovels, picks and other tools.

“We’re to build a fence,” said Vasilisa with certainty.

The chicken legs, which had stood quietly for most of the day, now moved. Each leg stretched slowly and voluptuously, clawed feet spreading wide, toes wiggling. Baba Yaga’s house swayed and dipped slightly above them. One foot extended, the toes clamped together and dragged along the ground while the other foot hopped. The legs made a slow oval, scratching a deep line in the ground. When the oval was complete, the legs carried the house into its center and stood still again. The fire pit lay in one rounded end, blooming suddenly with flames.

“Find your bones!” said Nephthys gaily. They received no further instruction.

Vasilisa heard a sound of tapping. Baba Yaga squatted by the fire pit, a slender bone in each hand. On the ground between her bony knees sat the fiery skull, once again cold and dull. She tapped on the skull’s dome, maintaining an even, steady beat. The tap, tap of the sticks strengthened and deepened, became reverberant, as though the skull was a large hollow thing covered with skin. Boom-boom. Boom-boom.

Jenny sat next to her, and Vasilisa was glad to be near a friend. The drumbeat rolled against her, insistent and breathless. She reached in the pocket of her apron with her left hand and felt the doll. With the other hand, she explored the pile of bones, brushing lightly through them. The sky darkened and the fire burned high, sparks rising above it. Firelight threw strange shadows over the heaps of bones.

The others were intent upon the task, sifting and sorting. Artyom crouched across from her, face shadowed, running his hands delicately over one bone, then another. His hands drew her gaze, the sureness and tenderness of his touch. The drumbeat itched in her body, in her blood. She shuddered, aroused, and then the doll in her pocket stirred against her hand and she remembered what she was doing and turned back to the task.

ROSE RED

Rose Red settled and calmed. Boom-boom. Boom-boom. She remembered the Night of Trees. She remembered power in her hands like green fire. She closed her eyes and kicked off her shoes. The ground felt cool and springy beneath her bare feet. She drew in a deep breath and opened herself. Boom-boom. Boom-boom. She rubbed her hands together and then ran them over cheeks, collarbone, breasts, belly, hips and thighs. Boom-boom. Boom-boom. She crouched and laid her hands lightly, questioningly, on a bone.

The sun went down.

MARY

Mary thought of the feel of seeds in her hands, their subtle vibration, the golden threads of light hidden inside their hard cases. She laid her hands on bone after bone, hearing the drumbeat. The others worked around her, with her, needing nothing and giving nothing except their presence.

ARTYOM

Artyom knelt, scattered bones spread out in front of him. Vasilisa was nearby and he was aware of her throughout his whole body. He didn’t turn away from that awareness, but carried it with him inward and downward. He closed his eyes. Let me find a way to do it right, he thought. The drumbeat roused something deep and primitive in him. He thought of the Firebird, its vivid joyous color, its wild mystery, its breathless beauty. He closed his eyes and caressed the bones as though they were the body of a beloved woman. The drumbeat throbbed in his blood. He ran his hands tenderly over a landscape of bone, exploring, shaping his flesh to their contours. He felt their texture with sensitive fingertips, rubbed against them with his palms. He felt an impulse to raise them to his lips and lick them, press them against his cheeks. His hands roamed over the bones and then he felt warmth under one of his palms. He moved away from it, questing with his hands, and found only coolness. His hands returned and met warmth again. He opened his eyes and picked up the bone. It was getting dark. The drumbeat had died away. The bone in his hands looked quite unremarkable. Nothing distinguished it from the jumble on the cloth, but he set it aside and began searching through the pile again.

JENNY

Jenny had feared Baba Yaga ever since she’d known Vasilisa and heard of the terrible old hag. Now she found herself in the Baba’s presence with this strange group of people, and her fear diminished in their company. Rumpelstiltskin was near. She looked at the bewildering jumble of bones in front of her and didn’t know how to begin. The drumbeat invited her to fall into it, but she resisted. She remembered a stone cell and piles of dusty golden straw. She remembered a long night and Rumpelstiltskin’s voice.

The old cradle song rose to her lips, fought against the rhythm of the drum. She wanted to put her fingers in her ears, screw her eyes shut, and sing the song loudly, drown out the alien beat. She must remember the cradle song. She must! Panic rose in her, making it hard to breathe…and then the drumbeat softened, quieted. Was it? Or had she only imagined it? No — there — it diminished. Every beat sounded flatter, shallower. The rhythm slowed…slowed…now it was just a tapping, as it had begun. Tap-tap. Tap-tap. The fire popped and sounded louder than the drum. Tap-tap. Tap. Tap. Tap.

The song rose from within Jenny, rose in a hum tasting of morning sun and honey, a sound full of heart, full of tenderness and love. She let it come, feeling it shape her tongue and lips. She felt the presence of her mother brush against her, warm and soft as sunlight.

From somewhere across the fire pit, another voice joined in the song, rather hoarse, gruff, a beloved voice. Growing in strength, it led her, dropped behind, followed her. Rumpelstiltskin. She laid her hands on the bones, singing, and waited for them to sing back.

KUNIK

Kunik heard the cessation of the drumming and the rise of the cradle song. The firelight caressed Mary’s head as though it loved her. Her hair was the color of sun on corn, rich and thick. The little girl with hazel eyes had grown into a beautiful woman. She’d shown him her seeds, and told him something about what she’d been doing. He thought of the little brown rabbit, Surrender, come out of Mary’s dream and his story from the deeps of winter to this spring night.

Surrender had guided him here, to the circle of firelight where he knelt with the others and sorted through bones. A selchie came to him as he floated in his kayak in the northern sea, bringing an invitation to initiation between one life and another. She told him he’d be provided with a guide if he chose to accept. She also told him secrets would be revealed, though she wouldn’t say what kind of secrets. Following the selchie’s directions, he’d come to shore and found Surrender, still in his white winter coat, waiting for him.

Together they’d traveled from North to South, from winter to spring, Kunik shedding his winter gear and Surrender shedding his white coat, until they’d reached this place, this spring night, this strange circle of people and his old friend Mary.

He was glad he’d accepted the invitation.

One of the young women sang, leading the other voice coming from somewhere outside the reach of firelight. He had a swift, elusive memory of another woman singing a song to a beloved child in a place where snow drifted like fallen stars and the night sky rippled with color, and then it was gone. He began to run his hands over the bones. Bones and seeds, he thought. Bones and seeds…

Methodically, one by one, Kunik picked up each bone, holding and turning it in his hands. He searched for shape within bone, shape of animal or bird or fish — or fence. He felt with the tips of his fingers and the receptive flesh of his palms for patterns, planes and lines and curves, the essence of the shape locked within.

Some bones were long and others small and rounded, or thin and blade-like, or curved. He piled some carefully at his side, putting the discards in a heap in front of Radulf, who sat next to him, stirring his hands and forearms through the pile as though in a dream. Kunik saw the others also discarded into this pile. Each one used his or her own method of finding their bones. Radulf was the only one up to his elbows in a pile.

RADULF

Radulf knelt before a pile of bones and thrust his hands into them, feeling smooth weight and rounded corners. His fingers found cracks and chips and pits in the bones. The bones made a clunking sound as he stirred them, bumping against his wrists and arms. He heard the drum beat and the song, but distantly. Some part of him remained aware of the fire, popping and cracking, warming the air around it, but distantly. He had no goal and no desire. He stirred the bones, flexing and moving his hands and fingers. He stirred the bones, round and hard, long and curved, whispering and murmuring in muted clicks.

Radulf had been traveling for a long time. He’d left behind youth, wealth, inheritance, his people and the life he was expected to live. He’d been married, once. The memory of that had kept him alone and on the move.

For years, he’d stayed near the sea. It hurt him, but he couldn’t leave it. At night it spoke to him, sang to him, clung to him. He’d nearly drowned at sea as a young man. He loved it, but after some years he felt haunted by it. Finally, he tore himself away and moved inland. He’d run across Dar a time or two, but preferred to travel alone and avoid notice.

Then he encountered Artyom, hunting on horseback with a group of nobles who stopped to question the stranger. Radulf drew himself up proudly and refused to give an account of himself. The forest wasn’t private; he had as much right as they to be in it. He looked, and indeed was, prepared to defend himself with skill and ferocity, and they left him there, stubborn and silent.

Artyom, near the back of the group, stopped and dismounted and had spoken so courteously and with such warm interest that Radulf unbent. They became cautious friends. Artyom was young and Radulf middle aged, but they were comfortable with each other. Artyom invited Radulf to stay with him and his entourage. Somewhat to his own surprise, Radulf agreed.

Artyom traveled with a human skull, a frail, worn looking object, not at all grisly. Radulf had first seen it one day when Artyom invited him to his room after the evening meal. The skull sat on a table from which perch it observed the whole room. Radulf stretched out his hand to pick it up, but thought better of it and withdrew before touching it. Artyom smiled somewhat ruefully, said “Light!” and the skull burst into a fiery glow. Radulf took a hasty step back.

Artyom left the skull burning while they sat down in front of an open window. It had been a damp night of fog. A fire burned on the hearth. The wet air felt pleasant on their faces, refreshing in the over-warm room. Artyom took off his coat, an elegant garment of brocade and gold thread, revealing an embroidered linen shirt underneath it.

“I’ve told you my father was a ruler.”

“Yes,” said Radulf. “And you’re traveling, making alliances, before going home to take his place.”

“Yes. My father’s advisors and ministers are taking care of business in my absence. While traveling, I heard of a woman who spins linen so fine it can be drawn through the eye of a needle. I was interested, and it happened I needed new shirts, so I asked a servant to buy a length of good linen from her. It was fine, so fine I couldn’t find a seamstress willing to put scissors to it. I tracked down the weaver, thinking perhaps she would make the shirts. I discovered one of my own countrywomen. It was the first time I’d heard my own language since I left home.”

“Remarkable,” said Radulf.

“Indeed. Her name is Vasilisa. She agreed to make the shirts, so I delivered the linen to her. In its folds, I laid a feather from the Firebird.”

“The Firebird?”

“The Firebird is a creature from my country, a fantastic bird with glowing feathers. Legend says it leads one to treasure. Many think it’s only a myth, but the Firebird has honored my family with its presence through generations, and I’ve seen it. It comes and goes as it will, but I’ve flattered myself it keeps an eye on me. Every child of my culture hears stories about the Firebird, and I thought Vasilisa would like the gift. The feathers glow, you see, even after the bird has shed them, and they’re particularly beautiful. I sent her an orange one.”

He extended a linen clad arm to Radulf. Around the cuff of the sleeve a flowing pattern of a bird with a long tail and graceful wings was sewn in red silk thread. “This is one of the shirts she made me. They’re each the same, sewn with this pattern of the Firebird around cuffs, collar and hem.”

Radulf fingered the soft linen.

“They’re beautiful. Kingly.”

“She told me she’d never seen the Firebird, only heard of it. She imagined what it might look like and came up with this pattern.”

“She sounds special.”

“She is. I’ve never met anyone like her. The skull,” he nodded to the fiery skull, sitting on the stone hearth, “is hers.”

Radulf raised an eyebrow.

“We’ve only spoken a handful of times face to face, but the Firebird flies back and forth between us with notes.” Artyom spoke with some embarrassment. “I know it sounds silly, but I must keep up appearances and she has her living to earn. She gave me the skull, though. Said it sees clearly and she wanted me to keep it for a while.”

“A strange love token,” said Radulf, “and an even stranger go-between.”

“The Firebird, you mean? Yes. But it leads you to your treasure, don’t forget. What if Vasilisa is my treasure — and I’m hers?” He gnawed at a fingernail, already bitten to the quick. It made him look very young.

“That’s what I keep thinking — what if? It must be so. Why would the Firebird be involved otherwise? I don’t know what the skull means to her, or how she came by it, but I suspect it can somehow tell her what it sees. I want to convince her we belong together. With her beside me I could be the man I was meant to be.”

Radulf looked uneasily at the skull. “You don’t think…you don’t think it can see inside you too, do you?” he asked.

Artyom looked down at the hem of his sleeve, running his finger over the flowing border of red silk firebirds. “Of course not,” he said shortly.

“I was married once.” Radulf stood by the fire, turning his back and letting it warm his legs. “It was a long time ago. I didn’t love her but it was the expected thing to do, a suitable political and social alliance, and so I did it. I abandoned her one day, left without a word and never returned.”

“Did you love someone else?” asked Artyom.

Radulf winced. “I don’t know. There was someone I loved like a sister, but she disappeared and I never found out what happened to her. I’ve always felt it was somehow my fault.”

“I’m sorry, my friend,” said Artyom.

Radulf turned from the window and smiled at him wryly. “If that thing,” he nodded at the skull, “can truly see and hear us, it’s hearing all my secrets, isn’t it?”

“I suppose it is.”

A week after that conversation the Firebird appeared with a note attached to one leg. Radulf was with Artyom as he detached and read it. He was preparing to tactfully slip away and give Artyom some privacy when the other man stopped him.

“Don’t leave. This concerns you, too.”

Radulf halted his departure in amazement as Artyom read aloud.

“You and the man who travels with you are invited to an initiation, as am I and two of my friends. The Firebird has brought word from an old teacher of mine, powerful and wise. Understand it is an invitation only — you need not accept. I choose to go. If you or your friend wish to attend, the Firebird will guide you faithfully. You will not need your servants. I hope to see you there. V.”

Radulf opened his eyes, memory fading. His hands moved deep within a pile of bones. Firelight flickered around him. Now he could hear a sound of piping, insinuating and disturbing. The singing stopped. His hands had selected and set aside a pile of bones. Some were long bones for the fence but others were curved rib bones and what looked like finger bones and knucklebones. The others knelt around him in the dim light. He closed his eyes again, moving his hands through cool, dry death.

VASILISA

Vasilisa sat back on her heels, her back and legs feeling strained from kneeling over the bones. The group around her loosened, drew apart. They stood and stretched tension out of their backs. She looked around and saw each of them had set aside a pile of bones. In front of Radulf lay an unclaimed heap out of which he’d extracted and set to one side his own collection.

As she glanced around, Vasilisa thought it was like a game of Me! Not Me! There were no obvious differences in the bones they’d each recognized, and nothing set the chosen bones apart from the discarded. Yet she didn’t doubt her choices. She’d known her own bones and they’d known her.

Dar and Nephthys came forward. With a single glance, they evaluated the individual piles. Dar bade Mary, Radulf, Kunik and Vasilisa choose the longest and thickest of their bones, and he and Rumpelstiltskin helped them place fence posts. Rose Red, Jenny and Artyom chose smaller, slenderer long bones and a great variety of other shapes and sizes. As the fence posts were firmly planted, Nephthys helped them place the horizontal pieces of the fence. She bound the bones together with a huge spool of sinew from Baba Yaga. Rumpelstiltskin produced a sharp knife to cut it with. Vasilisa had her suspicions about the material from which the sinew was made, but kept them to herself. She avoided working with it, however.

Now and then, someone searched the discarded pile of bones for the right length to fill in a gap.

As they erected the fence, Vasilisa could see two places for gates, one at one end of the oval near the edge of the forest, and the other facing the open grassy meadow, about the middle of the long side.

Artyom and Kunik discovered between them they possessed the bones needed to build a gate. They laid the bones out and fit them together with fascinated enjoyment. Vasilisa thought it was like doing an elaborate puzzle by firelight. When the gate was complete, they bound the bones with lengths of the strong brown sinew and hung it from a fence post. This formed the gate near the edge of the woods.

The second gate was wider and more centrally placed. Everyone had pieces of it. By now the night was well advanced. Baba Yaga hadn’t stirred from her place by the fire. Nephthys gave guidance when needed but kept well in the background. Dar lent a capable hand with construction.

At last, they were finished. Pale bones glimmered in the dark. The fence enclosed the chicken legs and the Yaga’s house, the fire pit and the black iron cauldron. Vasilisa stood with the others, looking at what they’d built. A few bones remained, scattered across Nephthys’s cloth. All the rest had been used.

Baba Yaga rose from her place by the fire. She took a few steps, hitched up her ragged skirt and squatted. She grunted. The unmistakable sound of liquid hitting the ground came to their ears. She rose and without a look at the pale fence, the arched gates and the sturdy posts, she stumped over to her house. Ignoring the steps, she slapped at one of the chicken legs and at once they bent, the steps folding up like an accordion. When the house was low to the ground, Baba Yaga hoisted herself over the threshold and slammed the door behind her. The legs straightened, the windows snapped shut and the house darkened.

Vasilisa met Artyom’s eye and he gave her a weary smile. Dar opened the wide gate with a flourish of his embroidered cloak, and they filed out. The fire burned low. Rumpelstiltskin threw dirt on the embers with his shovel and followed the group, shutting the gate carefully behind him.

CHAPTER 19

VASALISA

Sunlight cracked the translucent morning sky. Vasilisa woke. She’d rolled herself in blankets and slept under Dar’s cart. She’d slept deeply, feeling safe and protected between the soft mattress of grass and the wooden underside of cart. When she opened her eyes, she was lying on her side. Thick stems of grass and flowers surrounded her and she looked into them as though into a forest. She felt invisible. She listened.

The birds were in full dawn chorus. They made such a clamor she couldn’t hear anything else for some moments. Then she heard the sound of Gideon grazing nearby, a contented, unhurried grinding mastication. She heard unfamiliar whistling and thought it must be Dar. She listened as he moved about, tending a fire, heating water and murmuring to Gideon. She heard the flap of blankets being shaken out.

Vasilisa thought of the fence they’d built the night before and wanted to see it in daylight. She rolled out from under the cart and sat with her back against one of the wooden wheels, still wrapped in a blanket, looking at the morning.

There was Baba Yaga’s hovel, high on its legs. One leg bent slightly at the knee, relaxed, giving the house a slight tilt. The door was tightly shut and the windows blank and shuttered. Baba Yaga slept. The house stood within a large oval of pale fence.

Vasilisa knew the fence was solidly built, but from a distance it looked slightly drunken because bones aren’t straight and true. It flowed and leaned, looking as though it was made for movement rather than boundary. It made her smile.

She could see the two gates, easily picked out because each was topped with a curving arch made of rib bones bound together. Near one gate, in an end of the oval, was the fire pit and a high stack of wood.

As she sat there looking, Mary and Nephthys came out of a stand of three birch trees. Mary combed her thick hair with her fingers.

Vasilisa turned her head, hearing a murmur of male voices, and saw Kunik had joined Artyom and Radulf for the night, nesting in thick grass as she had, though without any overhead shelter. A tendril of smoke wavered up and she smelled a campfire, though she couldn’t see the flames from her seated position in the high grass.

The thin sound of a flute came into the clearing and the White Stag and Artemis stepped out of the trees. The piper with them was an extraordinary figure. He wore a long crimson cloak, rich with decoration. Vasilisa saw short thick horns nestled in curly brown hair and a gold ring in his left earlobe. He stood on the legs of an animal, covered with thick brown hair and ending in split hooves. Dar left his fire, inclined his head before the White Stag, kissed Artemis on the forehead with formal affection and slapped the piper on the shoulder. The piper blew a series of short notes like laughter and took up his melody again.

Mary was transfixed at the sight of the piper, body tense, staring. Nephthys walked on, taking no notice of her frozen companion.

Some way from Vasilisa a head appeared in the grass, tangled curls black in the sun. Rose Red. She, too, watched the piper with wide eyes. At the same time, she shook out her skirt and apron, put her arms into her vest and fastened it up the front. The piper disappeared with Dar between the trees. Rose Red looked after them, a frown between her eyes, and then bent over and ran vigorous fingers through her dark mop.

“I’ll do your hair if you’ll do mine,” came Jenny’s voice. “I’ve a comb somewhere…”

***

Later, hunger satisfied and everyone washed and brushed as well as possible with cold water and a comb, they gathered again in a circle in the morning sun. Baba Yaga had yet to appear. No one spoke of the initiation that would take place that night, though Vasilisa knew it must be in everyone’s thoughts.

It was a pleasant day. Kunik, Artyom and Rumpelstiltskin announced their intention to find meat and set off into the forest. Radulf and Jenny volunteered to collect water and follow the stream in search of fish. Mary went to look for strawberries and greens. Dar strode back and forth from the forest to the fire pit with armfuls of dead wood. There was no evidence of his goat-footed companion.

Vasilisa shook out and folded blankets, retrieved Jenny’s comb, a knife, a carved lump of coral and other objects mislaid or lost in the grass during the night. She made a neat stack of shovels and tools used the night before and folded the unused bones in Nephthys’s tarp. She rewound the unused, unpleasant-smelling sinew with distaste.

She and Dar chose one of the campfires outside the fence and enlarged it. They would need a place to cook meat. Dar provided a spit and pot from his cart. They laid a fire and stacked extra wood.

Baba Yaga still hadn’t appeared. Nephthys slept in the warm grass. When Dar judged they’d gathered enough wood, Rose Red wandered over to Gideon. The White Stag browsed nearby on the edge of the woods. She curried and brushed the horse, more for the pleasure of it than any necessity. She combed out his mane and tail and threaded them with flowers. Dar leaned on his elbows in the sun and watched.

“As soon as you’re finished, he’ll roll,” he predicted.

The horse blew out a breath and lipped at Vasilisa. “It doesn’t matter,” she said. She felt lazy and peaceful in the tender afternoon.

The White Stag joined them. She made a garland of tough grass and flowers and set it in his antlers.

The hunters returned with meat, already skinned and dressed. Dar lit the fire and began to cook. Nephthys woke. Mary returned, and then Jenny and Radulf, damp and happy with a string of fish.

As the afternoon lengthened, they ate, comfortable with one another, but Vasilisa felt an increasing tension as evening approached. As they finished eating, a door slammed. Baba Yaga was awake.

The old crone ignored the group on the grass. She stumped around the inside of the fence. She glared. She muttered. She shook her head in disgust. As she passed Kunik’s and Artyom’s gate, she kicked it viciously. It held. She stepped onto the lowest cross bone of the wide central gate and pushed against the ground with her foot. The gate swung back and forth on its hinges with her full weight on it. It made a sound like bare tree branches rubbing together in a high wind. She looked like a malevolent thick toad on a merry-go-round made of bones. She stepped off. The gate didn’t sag or break.

Baba Yaga stood with her hands on her hips on the threshold of the open gate. Her iron gaze swept over them.

“What are you waiting for, toadlings?” she shrieked. Her gaze looked beyond them, towards the edge of the trees. Her mad grin looked like a gash in her face. “Come in and play, sweet ones — if you dare!” She shrieked with glee.

A figure strolled out of the trees. It glowed with a pale soft light that matched the fence. Under the domed skull gaped wide empty eyes, a pit of a nose and an expressionless grin.

A skeleton is a sexless thing, yet Vasilisa immediately identified the newcomer as “he.” It was something about the graceful power with which he moved, the subtle swagger of an attractive male who knows his legs are well shaped, his buttocks hard and strong, and his flesh laid in just the right way over his frame.

Vasilisa thought him the most vividly alive thing she’d ever seen. His confidence took her breath away. He was as naked as bone, so naked one could see right through him, yet insouciant and vital and real.

“Here’s my pretty boy! Here’s my bony one!” The Baba purred and passed her hands over her breasts, pinching her nipples through the coarse, ragged tunic she wore.

Death came to meet her, grinning his hungry grin. She lifted up the hem of her skirt and pressed his hand beneath it. His elbow moved and she leaned against the fence, legs spread wide. She turned her face to his and thrust her tongue between his teeth. She put her hands on his cheeks and licked his naked mandible. She thrust her hips against his moving invisible hand, groaning and gasping and cursing, and then shuddered. Still shuddering, she pulled the hand from beneath her skirt to her mouth and licked the white finger bones with slow deliberation.

A round sphere fell out of Death’s right eye socket, pinged against a rib and fell to the ground. It was followed by another, then three from his nasal cavity. More fell from his grinning mouth like a cascade of foam, black, red and ivory. They scattered around Death’s bony feet, the color of corruption, blood and bone.

Vasilisa, like most of the others around her, stood frozen in appalled silence. Dar grinned. Artemis remained aloof and Nephthys paid no attention to the macabre sexual display but clapped her hands with pleasure as marbles fell from Death’s head.

The Baba crouched and gathered the marbles with a sweep of her hand, grinning like a child stealing candy. She went to where her black cauldron squatted on the ground near the fire, tipped the marbles into a sack and withdrew a skull. Without word or pause she threw it at Death. It flew straight through the air like a large white bullet and Death reached out and caught it casually. He pressed his grinning teeth against the mouth of the skull with a hard click, and it burst into fiery light. He balanced it atop the nearest fence post and turned, graceful as a dancer, and caught the next skull speeding toward him

.

In this way, Death pranced around the fence of bones, lighting what Vasilisa thought of as the arena, while Baba Yaga fired skull after skull at him. He caught each one, pressed its teeth to his in a grotesque kiss, and placed it carefully, facing inward.

Artemis spoke.

“On this day comes the hour of perfect balance.” Her clear gaze rested on each face. “Do you choose to enter the gate and take your place?”

Mary, without a word, left the group and walked through the gate, brushing resolutely past the obscene figure of Baba Yaga and the grinning skeleton next to her, Surrender at her heels.

One by one, Vasilisa and the other initiates followed, guides and leaders coming behind. Artemis and the White Stag brought up the rear and Artemis latched the gate.

ARTYOM

“Once upon the time there lived a maiden. Oooh, she was sweet as the sweetest morsel on the tongue! Oh la la—what a pretty little maiden! What a weak, innocent, puling little maiden she was!”

The fire was lit. Baba Yaga had gathered them into yet another circle within the bony circle of the fence. They sat on the grass. The Baba rested on an overturned bucket. Without preamble, she began. This was not like the storytelling that had come before. Artyom felt tense and expectant. The fire crackled and popped hungrily and the last light drained out of the sky.

“One washing day this little Vasilisa, this pretty little maiden, was hanging out clothes to dry in the sun. I had the misfortune to pass by, and she smiled and waved and wished me a good day. She was so sweet I wanted to step on her and see that sweetness ooze out of her cracked bones. So, I turned her into a frog.”

Vasilisa gasped. Rose Red, next to her, put out a hand in concern and Vasilisa struck at her, slapping the hand away. She stood clumsily, as though her legs felt numb. Her face looked rigid in the firelight. Her eyes remained fixed on Baba Yaga in horror and something like hatred. Artyom had never imagined Vasilisa could look like that. She staggered back a step or two, out of the circle, shadows concealing her face.

Baba Yaga continued, her gaze fastened on Vasilisa’s hidden face, her voice cold and relentless.

“She hopped away, weeping tender little glittering tears like fish scales, wondering what she’d done to deserve such a terrible fate. No more waving and smiling and wishing strangers good day for her!

Well, I kept an eye on her to see if she’d be more interesting as a frog. She hopped and she hopped and eventually she came to the King’s palace. Around the palace, you must know, are parks and gardens, and in one of the furthest gardens stands a huge old birch tree and under that is a fountain.”

The mention of the King’s palace shocked Artyom. It couldn’t be! But as the Baba continued inexorably, he saw in memory the birch tree, its peeling trunk, and the old neglected fountain, slippery and smelly with green and black scum on stagnant water. His stomach clenched in a cold knot. He put a hand to either side of his head and pulled his hair as though to tear his head apart. He wanted to put his hands around Baba Yaga’s scrawny throat and silence her forever. She eyed him mockingly as she talked.

“The fountain hadn’t worked in a long time, so it had become a stagnant pond, and a lovely dank, muddy, fetid place it was!”

Baba Yaga smacked her lips reminiscently and rubbed her hands together, fingernails clicking and knuckles popping.

“This hidden old fountain was the favorite hiding place of the King’s youngest son, who was a spoilt, weak, loathsome little tadpole. He was too obnoxious even to kill and eat. He hated everyone — but not more than they hated him, miserable spawn! He possessed a great treasure — a golden ball. He took it every day to the fountain and played with it, entertaining himself, as no one else wanted to be near him.

One day he was tossing the golden ball in the air and catching it in the aimless manner of a useless child, and somehow…”

Here she stopped and cackled, looking malevolently around at the listeners.

“Somehow, he threw badly and his pretty golden ball fell in that nasty, dark water! Of course, the brat howled about it — but no one came because no one cared, and he was too precious to guddle about in muddy water himself — make no mistake about that! A puffed-up little princeling, that one was!

Well, guess who popped her head above the water to see what the fuss was about? Ssswwweeeeet, good little Vasilisa, of course — who else? Even living in a sewer hadn’t changed her a bit, curse her! Just as boring and sickening as ever.

And ‘Oh, what’s the matter little boy? Why do you cry? How can I help you?’

And the cub wept and pouted and gulped like a toad in the rain and Vasilisa swam right down to the bottom of the fountain, found the ball and brought it back to him.

Well! Then things began to get more interesting! Now the little pisswort possessed a new toy, a live toy! He began to wonder what sort of games would be fun with this kind of toy!

Then he conceived a brilliant idea. He’d heard the servants and gardeners talking about hunting for frogs. He stole a gig — a sharp-pronged, murderous little gig it was, with the blood of a thousand frogs on it — from one of the under gardeners and snuck out one night with his golden ball for a light.

He made his way to the pond. He set the golden ball down on the edge of the old fountain, and in a coaxing, wheedling voice, called his ‘little friend’ and his ‘dear one.’

Of course, she came, the stupid girl! She swam right up through the dark water to that glowing golden light. He was ready and he struck with the gig. I thought he might make an end to the bitch then and there, but they both proved incompetent. I might have known. He, being unskilled, struck off center and too slowly and she, even though stupid, possessed something of a frog’s quickness and jumped aside. The gig pierced right through her back foot, though. She disappeared under the water with a single splash and when he pulled out the gig, he found a piece of her foot with two toes attached to it. The nasty little worm could hardly wait to get it into the light to see what color frog blood was!”

Artyom felt bitterness rise into his throat, leaned over and vomited in wrenching spasms of fury. Tears ran from his eyes and mucus snailed out of his nose in slimy ropes. The taste of vomit made him retch again and again. Long after his stomach was empty, he heaved in aching reflex.

Slowly he became aware of a cold, wet pad of cloth on the back of his neck. He closed his eyes. That someone dared touch him, comfort him, even, as he sat there in his own vomit, nearly started the retching again, but he controlled himself, forcing breath through his mouth in shallow gasps. He groped blindly for the cloth and felt another put into his hand, cool and smelling of sweet water, not the brackish, filthy water he remembered from so long ago. He wiped his face, spit, blew his nose. His hands trembled. He wanted to move away from the stench of his vomit, to hide from it, but he refused to show weakness. He would not be further shamed in front of them.

He raised his chin and glared around the circle of strangers, defying their judgement. Who were they? Nothings and nobodies. His blood was royal. He came from a line of rulers. What did they know of his desolate, lonely childhood? It was a plot, a conspiracy, engineered by the hag Baba Yaga to disempower him, humiliate him and frustrate his need for Vasilisa, deny him the balm of her love and admiration, the peace of her strength.

Firelight flickered on the circle of faces. The place next to him, where Radulf sat, was empty, and Radulf stood at his shoulder. It was he who’d wet squares of cloth in water and come to Artyom’s aid.

No one said a word. Baba Yaga squatted on her bucket, a lumpy dark shape. The others remained silent and still. Artyom tried to make out Vasilisa’s expression, but she stood in shadows outside the circle, her empty place like a wound.

She bent. She pulled off her boots, one at a time. He could see the white of her stockings as she drew them off her feet. She dropped the hem of her black skirt and walked through her empty place in the circle to where he stood, stepping deliberately in the puddle of vomit with her pale feet. Unwillingly, but unable to help it, he looked down at her mutilated foot. Two toes were missing, leaving a jagged scar. Deep dimples of penetrating sharp injury scarred the forefoot below the toe stumps.

“You did this to me. You did this. You did this?” Her voice broke, but he couldn’t tell if rage or grief that thickened it.

Artyom looked away from her stonily. He faced Baba Yaga. “Tell the rest,” he said. “The story isn’t done. Tell it all. Finish what you’ve begun, you heartless hag!”

“Listen, then children,” said Baba Yaga in a terrible voice. “Listen to the end of my pretty little story.”

“After that, little froggie got smarter. She hid herself from the boy, but after a time her foot healed and he returned every day and coaxed and pleaded and apologized and wept for his own loneliness and she decided — oh that sweet, sweet girl! — to give him another chance. After all, he was only a child. And nobody loved him! Poor little ugly scut! He’d said he was sorry.

She kept out of his reach, though, just showing her head above the water at a safe distance. But he was so contrite, so happy to see her, so abject, she began to trust him again, and one day she allowed him to touch her. Then she began coming to his hand when he called her and he bided his time and bided his time. Had a feel for the cruelty of the thing, so he did!

A day came when he closed his hand about her and picked her up. She screamed — oh yes, frogs scream — “catching sight of horrified disbelief on Jenny’s face. “Oh yes, my pretty tawdry piece of dreck, they do indeed scream!

“Yes, she screamed and screamed, that little sweet Vasilisa frog, but he paid no attention — not he! He drew back his arm and threw her as hard as he could against the trunk of the birch tree standing next to the old fountain. Splat!” She shrieked with laughter.

“Well, that should have been the end of her and all that useless sweetness. I was sick to death of her myself, and he certainly had no more use for her! But, well…” and she trailed off into incoherent mumbling and swearing.

Artyom, still standing, kept his face expressionless. The cold clarity of a soldier slid over him like armor. He shut away his emotions, controlled his anger and focused on evaluating and controlling the situation. He watched the others glance at one another in appalled silence, wanting to hear the rest and yet not wanting to. Vasilisa stood in the slimy, foul vomit, head hanging, her hair swinging down to hide her face.

“Hhmmpphh. Yes. Well, perhaps she was too sweet to die! Who knows? At any rate, she left, yes, she did, headed back out into the world to find someone else to nauseate.”

Into the frozen silence following the Baba’s last jeering words came a golden glow like a warm flame, like a candle, like a lantern in a dark night. It shone red and orange and yellow, the color of life and sun. It streaked out of the sky in a long, graceful swooping movement of trailing tail and wings. They turned their faces gratefully to its clean warmth. The Firebird came to rest on the blackened rim of Baba Yaga’s cauldron. An owl flew like a silent shadow behind it. It floated down and perched on a top rail of the fence, regarding them calmly.

Artyom heard Dar grunt, as though in surprised recognition. There was a sound of a single wingbeat, a puff of air, and the owl vanished. A young man stood next to the fence, lean and lithe, dark haired. His gaze moved with curiosity from face to face. When he saw Dar, he smiled and moved forward, and Artyom noted his lurching, clumsy gait.

The two men clasped hands. The Firebird lifted off the cauldron rim and rose and fell in the air over Vasilisa’s head, graceful and silent. The newcomer approached her, appearing to ignore the puddle of vomit and yet avoiding it neatly. She looked into his face, her own so wooden and shocked Artyom could hardly recognize her.

“My name is Morfran, lady, and you’re my aunt. The Firebird has brought me to you. I bring greetings from my grandfather, who is your father, Marceau, a King of the Sea.”

The words made no sense to Artyom. Vasilisa, he knew, was a peasant, and possessed no siblings. This was yet another trick of Baba Yaga’s, another attempt to humiliate and discredit him, to tear him away from his last, best hope of making himself into a beloved and worthy ruler, as his father had been. He needed Vasilisa. He needed her strength and her sweetness and gratitude. He needed to show them he was powerful enough to marry a peasant and elevate her to the level of a ruler’s wife.

He waited for Vasilisa to say something, but she simply stood, looking at Morfran, her feet in the stinking puddle of Artyom’s humiliation. She neither spoke nor moved.

Artyom glanced at Baba Yaga, who smirked and stroked her wiry chin whiskers with her thumb and index finger. She looked as though she nursed other revelations up her sleeve and could hardly wait to expose them. He hated her more than he’d ever hated anyone before.

Baba Yaga broke the silence. “Oh, yesss! If it isn’t the cripple! How dare you disturb us this night? Sit down, you whelp, and be silent! You’ll learn more of your fine family!”

She turned her iron gaze on Radulf, sitting next to Artyom. “How would you like a story, Wolf?” she inquired sweetly. “I’ll tell one just for you. A little lamb story, innocent and tender!”

Radulf met her gaze calmly but Artyom recognized uncertainty in his face. The name Wolf suited him well. He looked rather wolf-like with his lean body and thick dark hair, streaked with grey. He looked hard and canny and his eyes gleamed in the firelight.

Without a word, Rumpelstiltskin rose to his feet. He took Vasilisa by the hand. She allowed him to lead her out of the puddle. He knelt at her bare feet and spilled water out of one of the water skins, rinsing them clean. He took her back to her place in the circle next to Rose Red and she sat down abruptly, as though the strength left her legs. Dar draped a blanket around her shoulders.

Rumpelstiltskin picked up a shovel and scooped up the vomit, kicking dirt over the place. He disappeared beyond the circle of firelight for a moment and returned with the cleaned shovel, which he stacked neatly with the others.

It seemed to Artyom everyone breathed a sigh of relief and some of the tension left the circle.

Radulf reached up and tugged on Artyom’s hand and he sat, pulling away from Radulf’s grasp and clenching his fists, his eyes on Baba Yaga. Morfran took a place on the other side of Radulf.

The Baba watched this cynically, stroking her chin, smiling unpleasantly to herself. She opened her mouth to speak, but suddenly the Firebird, which had again come to rest on the rim of the cauldron, took flight with a sweep of its wings and flew across the circle like a ray of light, landing rather heavily on Artyom’s shoulder. He straightened automatically to support the bird’s weight, feeling comforted by its favor.

“Very well!” snapped Baba Yaga. “All cozy, then? All clean and comfortable? Everyone’s snotty nose wiped? Is everyone quite ready?”

“The Sea King’s a busy, busy boy! He has more than one daughter, oh yesss! Oh yesss! Good thing, too! He breeds them weak, does Marceau! One daughter falls in love with a patricide and is too sniveling to leave him when he abuses her. That one was your pitiful mother, boy!” She shot a look at Morfran, who looked down into his lap, his face hardening. Baba Yaga laughed.

“Another daughter is this little sweetling!” She glared at Vasilisa, who looked expressionlessly back.

“It’s not true!” growled Artyom. Baba Yaga shot him a glance of gleeful malevolence and continued.

“Now hear the story of a third daughter of mighty Marceau, a King of the Sea!