(If you are a new subscriber, you might want to start at the beginning of the Webbd Wheel Series with The Hanged Man. If you would like to start at the beginning of The Tower, go here.)

PART 4 YULE

Winter solstice. Return of the sun; birth and growth.

The Card: The Fool

Beginnings and endings; freedom from convention; innocence; impulsiveness; creative vitality; unlimited potential

CHAPTER 9

HADES

Hades stood looking down at the grave. Snowflakes fell dreamily, clinging lovingly to the young brambles Demeter had planted, one on either side of the simple polished marble slab Hades had chosen instead of a traditional marker. The stone was black, splashed with a golden color that reminded Hades of Persephone’s hair. He had not wanted carving on it, and rather than standing it at the head of the grave he laid it flat over the disturbed earth, leaving the surrounding ground scarred and bare so Persephone could plant flowers when she returned.

If she returned.

Hades shook his head. She would return. He must cling to that.

“Brambles are healing,” Demeter had said. “They symbolize remorse and protection from evil. They will watch over my granddaughter.”

Hades thought Persephone would approve, and so he and Demeter had planted the brambles together on the day he laid the marble over the grave.

Now, weeks later, the ground was frozen and the bramble canes looked spindly and dry. The land lay stark under a steel sky. A few days before a tremendous storm of wind and cold rain had felled trees and torn branches. Hades had brought a simple, slender wreath of spruce, cedar and hemlock and laid it atop the marble.

Every few days he left the Underworld and visited the barn where he housed his stallion, along with Persephone’s rabbits and other animals. He visited each stall and pen in turn, feeding cabbage leaves to the sheep and goats, scratching the pigs’ backs and grooming his black stallion while the horse searched his pockets for the apple he always brought for a treat.

Those who worked in the barns, garden and orchard greeted him with a nod or a smile as they went about their business. He had become a familiar figure, though a lonely and silent one.

After visiting the larger animals, Hades inspected the rabbit hutches lining one end of the barn. Since Persephone had left, he had not harvested any rabbits, nor allowed anyone else to do so. Persephone would return and see to them herself. He closely inspected their hutches, opening the doors and handling the soft creatures, stroking their coats and offering carrots and hay. When he had assured himself of their health and comfort, satisfied their cages were spotless with clean bedding and fresh food and water, he left the barn to visit his daughter’s grave, which lay next to Persephone’s garden, dormant and desiccated with winter.

These visits above ground provided a welcome break from the demands and chaos in the Underworld, a sideways step into his private life and away from his responsibilities. The peaceful winter scene and small grave at his feet held more reality for him in these moments than the dead souls in his care.

The loss of the child and Persephone’s subsequent absence had marked the beginning of a series of crises in the Underworld. Earthquakes, which had not troubled the Land of the Dead before, began to strike, making the earth groan and grinding stone together in a dreadful sound of anguish. Tunnels and caverns collapsed, blocking the steady flow of souls traveling across the Underworld’s threshold. Every spare hand, living and dead, worked to clear away the rubble, rebuild and shore up.

In these days his brother Poseidon had become his strongest support. He visited frequently, bringing news from the sea and its people. The two spent hours sitting by the fire discussing rumors and stories collected from the dead.

Poseidon, unlike his quieter brother, was gregarious and liked to travel. In these days he made it a point to explore parts of his kingdom he hadn’t investigated before, becoming familiar with the shyest and strangest sea creatures, searching for references to or information about Yrtym.

He also sent volunteers to assist in keeping the River Styx unblocked and flowing as it exited Hades and ran underground until it drained into the sea. Not only was Styx his gateway to his brother’s realm, but they did not know what effect blocking the river would have on the Underworld. If Hades flooded, what would become of the dead?

So many questions, Hades thought wearily, and so few answers.

Still, he must do what he could to save his kingdom and his people, and he felt grateful for his brother’s good humor, practicality and friendship.

If only he could have saved his queen and his daughter from tragedy and death.

He roused himself, lifting his bowed head and straightening his snow-dusted shoulders. He was cold. Delicate flakes frosted the evergreen wreath. Movement caught his eye and he squinted through the thickening snow toward the tree line, disheveled now with fallen and uprooted trees.

A cloaked and hooded figure approached him, moving with a kind of weary grace he recognized. He took a step forward, straining his eyes. Could it be?

The figure came faster. He took another step forward. She threw back her hood and her eyes were the only color in the world, blue-green, blazing with emotion, warm and passionate as a tropical sea. He opened his arms, still disbelieving, and Persephone cast herself into them.

CLARISSA

“I suppose you know the story of Orpheus and his lyre,” said Seren.

“Of course,” replied Clarissa, watching him unwrap his instrument. “Orpheus was the greatest musician the world has ever known. He married Eurydice, an olive tree nymph, but she died almost immediately, and his grief was unending. He went to the Underworld to beg Hades himself to return Eurydice to life, and Hades agreed she could follow Orpheus back to the living world as long as he didn’t look back before he’d led her out of the tomb’s shadow. He refrained from looking back all the long way up from Hades, but jubilant because he thought he’d restored her to life, he looked back before she’d left the tomb’s shadow, and she turned away and returned to the Underworld. After that, Orpheus played only for grief. He refused to take another wife and wandered the world, playing sorrow and pain, until he died. His mother, Calliope, one of the nine muses, set his lyre in the sky so the world would remember him. It’s called the Lyra Constellation.”

The wrappings revealed a tortoiseshell lyre, lovingly polished. Gut strings stretched between two gracefully curved arms.

“I’ll tell you a secret,” said Seren. “This is Orpheus’s lyre. Euterpe, another of the Muses, is a special friend of mine, and she thought it a shame Calliope refused to share Orpheus’s instrument, so she retrieved it, leaving other stars in its place so Calliope need not know. Euterpe said my skill is at least equal to Orpheus’s. After all, I’m living and he’s dead. He betrayed his talent because of a woman, but I’ll never betray mine.”

He ran his fingers lovingly over the strings; the sound shimmered in the stone-walled round room.

Clarissa, who had reached out a tentative hand to touch the lyre, retracted it when Seren pulled it out of her reach, set it in his lap and began to strum. “It’s beautiful,” she said, watching his graceful fingers caress the strings. “Will you tell me about the Norns? Have you made a story?”

“I have,” he said, looking down at where she sat at his feet and smiling fondly. “A new story, and you’re the first to hear it. You’re becoming my muse, Clarissa!”

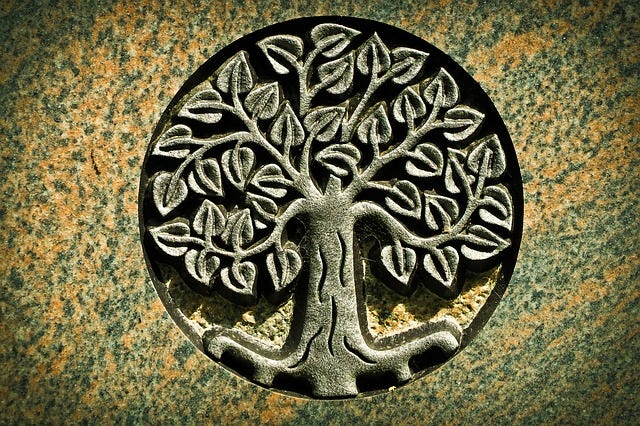

“Once upon a time, before the shining stars learned to sing enchantments, a tree stood at the center of the cosmos. Its roots wove together a planet and its branches supported the sky. It was a mighty Ash tree with three trunks, and it drank from the well of Urd. Mirmir, a great serpent, guarded the tree, whose name was Yggdrasil.

Yggdrasil, the pivot around which the wheel of life turns, the axle that turns cycles and seasons, ends and beginnings. Yggdrasil, the top of which cannot be seen and the roots of which are endless as they weave a world of rock and soil. Yggdrasil, the spinning distaff around which life is wrapped before being spun, cut and woven, though none can see it whirl.

For long ages, Yggdrasil stood, kingly and inviolate at the center of all, but one day something changed. Perhaps the invisibly spinning distaff faltered. Perhaps the Well of Urd became tainted, or the serpent Mirmir grew old. Life and death became unbalanced. Beginnings and endings fell out of symmetry.

Suddenly, the whole world of Webbd was threatened.

In times of fear and breakdown, people look to heroes, those with brave hearts and superior skills. The terrified world implored one such man to journey to Yggdrasil and discover and heal whatever was wrong. This man possessed the gift of music, and the whole world stopped to listen when he played. Trees and rocks uprooted themselves to follow his song, and every creature within hearing of his voice and instrument was touched with magic as he passed.”

Seren paused and played a lilting melody. Clarissa thought she’d never seen anyone as beautiful. His grey eyes shone with dreams, his mouth curled in a smile, and his long, sensitive fingers caressed the strings with skill and confidence, making her mouth go dry when she imagined them on her body.

He met her gaze and smiled into her eyes. She felt as though his look penetrated to her very bone, making her thoughts and desires visible to him. His eyes were light and clear, almost silvery, without depth. They were like stars, those eyes, like the white light encircling his brow when he was a baby. Clarissa thrilled with the knowledge that behind those eyes such talent lived, words like gems, stories of passion and adventure, music so piercingly beautiful that mountains and forests leaned down to hear it. His sensuality and passion matched her own.

And he was here, with her, at the lighthouse, and called her his muse.

“Humbly, the chosen hero agreed to undertake the journey to Yggdrasil and see what might be done. With his lyre he traveled, and music, poetry and stories graced his path. As he journeyed, he thought about beginnings and endings and formed a plan to rebalance them.

Others were drawn to Yggdrasil as well, a child, a group of elders, a Dwarve and a young mother. From every direction they journeyed to the center, not knowing they were the coarse material from which the hero would weave healing with his music, his words and his stories, and thus restore Yggdrasil and save Webbd.

When the hero arrived, he found everyone waiting for him. The old women who lived near the tree and used its power to spin thread and yarn greeted him reverently and joyfully. At his request, they hung fabrics of silk, linen, velvet and cotton over Yggdrasil’s lower branches to fashion a tent large enough to work in, using braziers for heat. The hero gathered everyone around the trunk and instructed them on his plan. He helped them understand beginnings and endings are forever bound together, and such things as seeds, bones and dead souls constitute both. Thus, he directed them in gathering these ingredients, certain that he, with is musical skill, could combine these ingredients into life, into endless beginnings arising from endless endings. He proposed to weave the strands of chant, lament, seed blessing and harvest prayer together, along with drumbeat for the tree’s roots, the horn for its crown and the lyre as a musical loom and shuttle.

Trustfully and respectfully, they followed his direction until at last he felt ready to begin. He sent a silent prayer to the star that had touched his brow with white light and began to play.

He never knew how long it went on. The horn soared in a wordless lament of closing gates and sky darkened by flocks of birds on the wing. It spoke of dark winds and starless nights under a sickle moon. It moaned of loss and bitter grieving, of wounds that never heal. The horn summoned the lost spirits of the dead, summoned them, gathered them and lay them down with bones, and the bones themselves made a scaffold, a framework, as he chanted over them, chanted and danced, pouring his words and music over them. When bones and spirits were joined together, he turned to the seeds, which he held, a handful at a time, letting his silver words and holy breath wash over them as he recited a blessing for growth, for bud and flower and fruit, for death. These he sprinkled over the bones and dead spirits, and each seed was like a glowing ember, a firefly, a warm-hued gem, because of his blessing.

All the while, whether chanting, blessing, singing a prayer or giving voice to horn and drum, he played his lyre, the heart of his skill and talent, and the lyre ascended above all the other elements and bound them together until the distaff of Yggdrasil spun again, the spinning wheel revolved, and new thread flowed through the old spinner’s fingers.”

“Oh!” breathed Clarissa. “How beautiful! How lucky you were there! I wonder if fixing Yggdrasil will fix the other strange things happening.”

In the magic of Seren’s presence and storytelling, she’d forgotten her worries and put away the ominous feeling that never quite left her these days. Now she remembered.

The sea had withdrawn from the land. She was still trying to believe it. She’d stood on the cliffs, or looked out from the tower windows or down from its apex more times than she could count, but even as she looked at the bare sea bed and the distant haze of water, she couldn’t quite accept what she saw.

She’d gone to visit Marceau, a sea king who was like a grandfather to her, expecting comfort and reassurance, but found none. In many places along coastlines the sea withdrew from the land. No one knew why. No one knew what to do. In addition, the ocean appeared to be warming due to superheated vents opening in the sea floor and unusual volcanic activity. The increased temperature killed many sea creatures. It was so bad that Poseidon, who usually left governing to the sea kings, had called for a gathering to share information and discuss the situation. Clarissa had never heard of Poseidon taking an interest in anything other than his wolves, horses and beautiful women.

After talking with Marceau, Clarissa returned to the lighthouse. Rapunzel, though preoccupied and concerned, was more comforting company than the merfolk, who felt their very existence to be in jeopardy as the food web unraveled. Persephone had left the lighthouse to return to Hades and her husband, and Clarissa missed her. Rapunzel lacked Persephone’s maternal warmth. On the other hand, Rapunzel was full of stories, fascinating facts and bits of witchlore, and Clarissa, lonely and frightened by the sudden wrongness of the natural world, found forgetfulness and relief in learning from Rapunzel.

Rapunzel had discovered the cellar, and Chris’s mural.

“If you’d asked me, I would have told you about him,” she said to Rapunzel. “When I came back, after my father was gone, I didn’t even think about the cellar because of meeting all of you, and the dance, and then Seren. That’s usually how I visited, through the pool in the cellar, but now I can’t use it, obviously.”

“No. Your brother swam as far as he could and walked the rest of the way. It turns out there’s also a passage into the cellar from Dvorgdom.”

“Dvorgdom?”

“The underground kingdom of the Dvorgs. I’ll tell you about it. Chris brought me a letter from Radulf.”

“I love Radulf. I wish Chris had waited; I haven’t seen him since Father died.”

“We didn’t know when you’d return, and he wanted to get back to Radulf.”

Seren, after leaving the tower a few weeks previously, had traveled to Griffin Town, where he reclaimed his lyre and other belongings from the ship he’d been thrown from. He’d sent word to Clarissa from there that he traveled to Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, where there was evidently some kind of trouble.

In his absence, Clarissa tackled her father’s papers and books, a task she’d felt unable to approach until now. Persephone and Rapunzel had looked through some of his writings before they’d met Clarissa, but after she revealed herself Irvin’s desk remained undisturbed, waiting for her attention.

The sharpest edge of her grief had dulled, which made her feel vaguely guilty. It seemed wrong to forget him so soon and so easily, as though she hadn’t really loved him. She dreaded reading his words and handling his beloved books, and was surprised to find comfort rather than pain as she paged through familiar volumes, reading a stanza here and there and finding well-loved but half-forgotten illustrations, for these had been her books, too, companions of her childhood. She well remembered Irvin reading aloud to her and her brother.

Her father had collected and written far more stories than she’d realized, many of which sounded familiar, but she hadn’t realized originated with him. His stories sounded as though they’d been handed down for generations, and without his notes she couldn’t recognize oral tradition from new material. Rereading them, she heard her father’s voice in memory and discovered an intense desire to pass the stories on, though she would never be the storyteller her father had been.

Clarissa gleaned from Rapunzel every bit of information she possessed about the Tree of Life. Rapunzel had not seen it herself, but friends of hers had, and she’d learned about the Well of Urd; Mirmir, who guarded the well and tree; and the three Norns from Elizabeth, her foster mother. She didn’t know exactly what was wrong with Yggdrasil, but she told Clarissa she’d lately heard one of the Norns was ill, and their work with Yggdrasil interrupted.

“He also said Yggdrasil is dropping twigs and branches from its top. You remember I told you no one has ever seen the top of the Tree of Life?”

Clarissa nodded. “How do they know the twigs and branches are coming from the top, then? And who is ‘he’, the one who told you? Did someone come while I was gone?”

“I’m told the twigs and branches are crusted with stardust,” said Rapunzel matter-of-factly. “That’s how they know they’re from the very top, where the upper crown entwines with the night sky. ‘He’ is an old friend of mine. You remember I told you about the tower I lived in when I was your age, and how I cut off my hair and climbed out?”

Clarissa nodded again.

“While I lived there, I made friends with a colony of bats roosting in the tower above my bedroom.”

“A bat told you about Yggdrasil?” Clarissa was astounded.

“A little brown bat, to be precise. His name is Ash. He hunted around the lighthouse and one night I spoke to him in his own language, and he recognized me.”

“Aren’t bats dangerous?”

“No. Bats are highly intelligent creatures, and most of them eat insects or fruit. They can bite, but generally only will in self-defense. They eat millions of insects, bats. Without them, we’d be overrun with flying insects. Ash is quite charming. He’s a mimic -- can impersonate anyone. He should be hibernating by now, but I made him a proposition and sent him on an errand. I’m waiting for him to reappear. If he doesn’t, I’ll know he decided to find his colony and hibernate, but I’m hoping he’ll help me this winter.”

“How can a bat help you?”

“He can gather news for me. He’s great friends with Mirmir. That’s how I heard about Yggdrasil. Bats can be in buildings, in caves and caverns underground, and in hollow trees. They’re noiseless on the wing and people rarely see them, as they only move around in the dark. Their hearing and eyesight are excellent. Ash would make a first-rate spy, and he could bring news from places I can’t reach.”

“What’s the errand you sent him on?”

“I sent him to find a volunteer insect to help him stay alive this winter. I could charm it so it never loses its life and Ash can eat it as many times as he needs to. An insect would be lightweight and easy for him to carry with him. He only eats insects; that’s why bats hibernate, because there are no flying insects for them to eat during the winter.”

“But nobody would volunteer to be eaten again and again, surely!” exclaimed Clarissa.

“Maybe not. We’ll see.”

“If he comes back, can I meet him? Will he mind?”

“He won’t mind,” Rapunzel had said, smiling. “I’ll let you know if he comes back.”

“Clarissa, you’re a million miles away,” said Seren, frowning.

Abruptly, Clarissa recalled herself to the present moment. “I’m sorry,” she said. “Your story made me forget, but now I remember again how frightening everything is.”

“You mustn’t be frightened. I’ll take care of you.” Seren set the lyre down and cupped her cheek with his hand. His touch made her belly blossom with warmth. She lost herself in his eyes, longing for more.

“You’re beautiful, little sea maiden. Your eyes are almost as lovely as mine. I’ve never met a girl like you.”

“But you must know all kinds of women; beautiful, rich and powerful women who’d be proud to be by your side and support your talent.”

“Yes,” said Seren. “I like women, and they’re attracted to me, but you’re not like them. When you’re listening to me, I feel like a god. You inspire me. I’d like you to always sit at my feet, just as you are now.”

Clarissa turned her head against his hand, allowing her teeth to graze the fleshy mound below his thumb, and kissed his palm, letting him feel her breath and her moist mouth.

“I’ll sit at your feet as long as you want me to,” she said. “I can’t think of a better way to spend my life than to support who you are in the world.” She closed his fingers over her kiss and returned his hand to him.

“What a shame you’re not human,” said Seren. His pupils dilated and she knew her kiss had excited him.

“I’m half human,” she said quickly.

“Are you? Is that enough?”

“Enough for what?” she asked, puzzled.

He looked away, as though embarrassed. “Never mind. I shouldn’t talk to you about such things. You’re not warm-blooded like humans. We have certain ways of interacting … physically, I mean. I have yet to find a worthy partner, someone who properly appreciates my sensitivity and passion. You wouldn’t think it, but the kind of skill and talent I possess come at a heavy price.” He sighed. “So many times, I’ve thought I’ve found the right one, but in the end she always disappointed.”

He talks like a man twice his age, Clarissa thought with tender amusement. He was only three years older than she.

“Seren,” she said, “if you’re talking about sex, I know what that is. How did you think merfolk children are made?”

“I haven’t thought about it,” he said. “I’ve heard the merfolk are cold and passionless, neither male nor female.”

“Don’t I look like a girl to you?”

“Yes, like a beautiful girl, but when you’re in the sea and have a tail, you don’t have a girl’s body. Perhaps you can look like a boy on land too, and choose not to.”

Clarissa had already learned how easily Seren was hurt, so she chose her words with care. “It’s true people make up stories about us because they don’t know any better. Most aren’t like you, so generous and interested in what’s true. The merfolk believe all life depends on a balance of male and female power. It’s the holy binary. We are like humans, in that we have either male or female bodies and reproductive abilities. We pay less attention to our presentation than humans do. Male and female merfolk decorate their bodies and their hair however they please and possess equal power in private and public matters. We rejoice in our physical forms. Merfolk are passionate and sensual, and we honor our bodies and those of others. I’m female. I could choose to look like a human male if I wanted to. No one would care. But I couldn’t be male, because I’m female. I look the way I want to look and I live in my body with joy and gratitude.”

“I see. Then how do your people …?”

“How do we have sex? The same way humans do, but our bodies are evolved in such a way that sexual violation isn’t possible. If we do not consent, our bodies cannot engage sexually. For us, sex is a sacred act of intimacy as well as procreation, and may take place between any combination of men and women. Sexual expression must be freely given and received in order for our bodies to allow it to take place, but we have no other rules controlling sexuality. Females also choose when to conceive. We cannot become accidentally pregnant.”

“I see,” said Seren thoughtfully. He slouched in his chair, Clarissa cross-legged on the floor at his feet, facing him. At some point she’d rested a hand on his knee and he’d taken it in his own and played idly with her fingers as she spoke.

“I’m hungry,” Rapunzel announced, coming down the stairs winding along the curved wall. She’d been on top of the lighthouse and wore a heavy cloak. She threw back the hood and hung the cloak on a hook beside the door. “It’s getting cold out. Shall we heat up the chowder?”

Clarissa gave Seren’s hand a squeeze and disengaged herself, joining Rapunzel in the kitchen. Seren announced he was going out for a breath of air and left after carefully wrapping his lyre and setting it aside.

Ever since Seren’s reappearance at the lighthouse, Clarissa had felt tension between herself and Rapunzel. Their growing companionship was disrupted, though Seren was reasonably quiet and always agreeable. Obviously, Rapunzel didn’t much like the musician, which Clarissa thought was mean of her. How could she dislike the greatest musician who ever lived? And he was so gentle, so sensitive and kind!

It was a bleak and bitter Yule at the lighthouse. The wind drove hard particles of snow against the tower and cliffs and salty ice crusted the exposed sea floor. Clarissa hadn’t spent so much time out of the sea before, though she’d frequently visited the lighthouse for a day or two when Irvin was alive.

Now it felt to her like a haven of warmth and comfort. The stove burned night and day and the light at the tower’s top sent its warning message into the long dark hours, even though no ship could come near the fanged rocks because of the sea’s withdrawal from the land. Still, Rapunzel tended the light in hopes one day or one night the sea would return to its accustomed place. For Clarissa, life centered around Seren, the sound of his voice, the shape of his hands, his slim male body and his eyes, so changeable and expressive.

She knew he might have spent Yule anywhere, been warmly welcomed wherever he wished to go, and felt grateful beyond words he chose to be with her, for certainly Rapunzel was barely civil and took delight in teasing him. Clarissa had discovered Seren didn’t like to be teased. It made him cross, but she knew the crossness hid a deep hurt, and she did her best to become a buffer between Rapunzel’s sharp tongue and Seren’s vulnerability.

It was a strain. Worth it, because Rapunzel was like … not a mother, perhaps, but the best kind of older sister, wise and full of information Clarissa wanted to know, and Seren was … well, he was everything. If she’d looked for a hundred years, she couldn’t have found such a perfect mate.

Not that they were mates yet, exactly. In fact, that was part of the strain. Rapunzel didn’t leave the tower, except to take a walk. Clarissa and Seren had no place in which to be private. Clearly, he couldn’t accompany her into the sea. He probably owned a fine home in a far-away city. Perhaps next year they would go there, so she could meet his friends.

She hoped it was near the sea, because she didn’t like to leave it for long.

She longed to be alone with him during the short, cold days and long nights. She imagined decorating the largest tower room where he slept, Persephone’s old room, with candles, imagined the deep soft bed freshly made with heavy linen sheets. She dreamt of being alone with him in front of the stove, the floor laid with thick sheepskin and strewn with pillows. She imagined being able to lock the lighthouse door and having all night to explore the texture of his kiss, discover every nerve ending and fold of skin. She imagined the heavy languor of her tail against his legs, then wrapping her own legs about him to pull him down against her, into her. He would run his fingers through her hair, cradle her face in his hands, and teach her what love could be between male and female. He would initiate her into the arts of pleasure, and she would learn how to please him. She would be the one he’d always searched for.

She would never disappoint him.

But the lighthouse wasn’t hers and Rapunzel lived there. During the days, Rapunzel stayed busy and, if anything, avoided Clarissa and Seren. They spent their days by the stove, talking. Clarissa worked in the kitchen and fed the fire. Every day Seren unwrapped his lyre and performed, and from him Clarissa collected a treasure trove of lyric, poetry, story and melody, much of which she wrote down so as not to forget, though he made it clear she was not to re-tell his material.

In the evenings, the three settled by the wood stove after dinner. Clarissa knew Seren much preferred the time she and he spent alone together, because Rapunzel insisted on taking turns telling stories in the evenings. Naturally, it was painful for someone as accomplished and talented as Seren to listen to stories poorly told, and Clarissa writhed internally when her turn came, knowing the inferiority of her language and presentation. She couldn’t even play an instrument. She watched Seren carefully, and as his face became aloof and distant, she pruned and truncated whatever she was telling so as to finish quickly and put him out of his misery.

Rapunzel, on the other hand, took a perverse pleasure in annoying Seren. She deliberately chose long tales and appeared to take no notice whatsoever of Seren’s pained expression or inattention. She told as though Clarissa was her only audience, and at times Clarissa became so compelled by Rapunzel’s story she selfishly forgot Seren’s discomfort.

During his turn, Seren came alive. He liked to stand with his lyre, sometimes moving gracefully around the room as he played and sang and other times telling stories with music weaving through the words like a gold thread, his grey eyes compelling, reading every nuance of his audience’s expression and reaction.

***

One day, just at dusk, as Clarissa set the table for their evening meal, Rapunzel came down from the tower’s top where she’d been lighting the beacon and said Ash had returned.

Clarissa wiped her hands. They went back up the stairs together. In Rapunzel’s room, upside down in the corner between the curved stone wall and the underside of the wooden floor above, hung a small creature with dark brown fur, about the size of Rapunzel’s hand. As they approached him, he spread his wings, and Clarissa saw thin, hairless membrane over a delicate scaffold of bones.

“This is Ash,” Rapunzel said. “Ash, this is my friend Clarissa.”

The bat swooped down, soundless and quick as a shadow, and attached himself to Clarissa’s heavy sweater. He examined her face with shining black eyes, his own shrunken visage so comical and wrinkled she smiled. He returned the smile, revealing sharp teeth.

“And I’m Beatrice,” came a tiny, shrill voice. A black beetle crawled out of Ash’s fur in the vicinity of his chest and waved her antennae. She was the same shining black as the bat’s eyes.

“Ah,” said Rapunzel with satisfaction. “You found a volunteer!” She leaned close to Clarissa and extended a finger to the beetle.

Beatrice strolled casually onto the offered finger and Rapunzel lifted her close so she could both see and hear the little creature.

“I’m Rapunzel, Beatrice. Ash has explained to you what we’re trying to do?”

“He has. You need information about the Tym, which is breaking down. My people are at risk, as well as Ash’s people and yours. The trees are dying. If he is to gather information for you through the winter, instead of hibernating as usual, he will need insects to eat.”

“That’s right. I can charm you so you won’t die, no matter how often Ash eats you. If you agree, you can sustain and companion him and he can keep you warm and ensure you’re fed as you travel.”

“We spent the day in a hollow tree and I am well satisfied for the time being,” said Beatrice. “But Ash is hungry. The flying insects are gone and most of the insects in the tree we roosted in hid under its bark. Please enchant me quickly so he can eat.”

As Rapunzel worked her spell, Beatrice, Ash and Clarissa watching, Clarissa thought the friendship between bat and beetle the strangest she’d ever seen.

“There,” Rapunzel said, and offered the beetle, still on her finger, to Ash. He regarded Rapunzel’s finger without moving, his face screwed up in dismay.

“Are you sure?” he asked, but Clarissa didn’t know if he spoke to Rapunzel or Beatrice.

“Yes,” said Rapunzel at the same time Beatrice said firmly, “Quite sure.”

“I trusted you,” said Beatrice. “You said you wouldn’t eat me and you didn’t. Now I trust her.” She nodded her tiny black head at Rapunzel. “You must eat, or you’ll starve and then neither one of us can help fix whatever is going wrong.”

Ash squinched his eyes shut, his tongue darted out and Beatrice disappeared. Ash munched once and swallowed, wincing. A moment later a shining black head parted the fur on his chest and Beatrice appeared again. “Here I am! Nothing to it!” Clarissa felt like cheering.

“It’s time for us to eat, too,” said Rapunzel. “We’ll leave you. The window’s ajar, if you’d like to go out, or you can spend the night in here, where it’s warmer. I’ll bring up some water. Later, we’ll talk and make plans.”

Rapunzel observed Yule, and as the solstice drew closer, she and Clarissa planned a dance to honor the new cycle. The day before, Clarissa took charge of decorating the old storeroom at the top of the lighthouse. Seren had mentioned several times he loved dance, and she could hardly wait to share the intimacy of it with him.

She was determined to look her best and chose carefully from the finery Ginger had left behind when she departed. Clarissa chose a lustrous grey skirt that caught the light and made her think of Seren’s eyes, and slid several thin silver bangles onto her arms. She would begin with a light tunic of the same fabric, but as the passion of the dance warmed and loosened her, she would take off the tunic and dance bare-breasted. She would show Seren she was a woman, his equal in passion, and a worthy partner. Perhaps in the glowing aftermath of ritual and sacred practice they would at last find a way to lie together, in spite of Rapunzel’s presence in the lighthouse.

Seren was restless and frequently went out to walk, in spite of the bitter weather. He’d explained to Clarissa he was accustomed to towns and cities, places lively with intelligent people and discussion where he could mingle with other well-traveled and sophisticated men. The lighthouse, isolated, lonely and without bright lights and entertainment, provided no scope for his talents. He remained only to be with her. He found their plans for honoring Yule quaint and rather old-fashioned, smiling indulgently at Clarissa’s preparations.

She supposed, from his point of view, honoring the cycles and seasons was childish, the kind of thing provincials did. Yet Persephone, Ginger and Rapunzel had revealed to her female power raised and shared through dance, and she couldn’t now imagine her life without it. She suspected Seren hadn’t danced as a part of a powerful female group, and could hardly wait to show him what dance could be. She would allow her body to express her desire and love for him in dance, and he would understand and join with her. She made preparations while Seren busied himself elsewhere, hugging her joyful anticipation.

Clarissa laboriously carried rocks up the tower steps, stacking and arranging them with candles of different size and thickness around the walls. She scattered shells and added a dried starfish and the coral lump Irvin had kept on his desk.

When the storeroom was arranged to her liking, she took two sheepskins that lay on the floor near the stove outside into the icy wind and beat them until they were fluffy and clean. She plumped up pillows and added candles to the main room. Usually, she spent the nights in the sea, returning to its embrace and song after a day spent on land, but she had slept by the stove before, and if she made it enticing enough, perhaps Seren, knowing she lay there, would join her after Rapunzel retired. It was the most perfect way she could imagine to honor the cycle’s longest night and celebrate Yr’s return.

The day of the dance, Seren and Clarissa went out together into the teeth of a rising gale. Wind blustered from all directions. As they stood on the cliffs looking out across the eerily exposed sea bed, the sky draped heavily over the lighthouse tower and it began to snow in billowing, rippling curtains. Clarissa spread out her arms and turned in a circle on the cliff, feeling the wind buffet against her and the cold tingle of flakes melting as they struck her skin. She laughed with delight, feeling primitive joy in the wild storm and the power of stone, sea and sky.

Seren laughed with her, suddenly seizing her in his arms, drawing her close and kissing her laughing lips. His skin felt cold and wet, but his mouth warm and the kiss pulsed through her body like a glowing sun. It was a kiss of seeking and finding; of promise given and received. It was rapture, passion, the heat of belly and thigh. It took Clarissa’s breath away and made her heart swell painfully with joy and gratitude. Nothing needed to be said. That single storm-beaten kiss contained the entirety of their commitment and joy in one another.

Clarissa spent the rest of the day in a daze. They ate their evening meal of thick stew and fresh bread early. They had let the fire go out just long enough for Clarissa to remove the ash and clean the stove, and the three of them lit it again in a ritual of gratitude and welcome for the returning light. Seren produced his lyre and tenderly unwrapped it.

“Oh, will you play for us?” asked Clarissa with pleasure. “I didn’t like to ask because I wanted you to be able to dance without worrying about making music, but if you and Rapunzel both play you can each dance as well.”

“I thought you and I would settle down by the fire while Rapunzel dances,” said Seren. “I know several Yule stories, and you set the stage so enticingly for me! I’m sure Rapunzel won’t mind.” He paused, looking at Rapunzel expectantly, but she didn’t say a word, her face a careful blank.

“But, Seren, we can tell stories after,” said Clarissa. “Sharing dance is the most important thing!”

“The most important thing to me is spending Yule with you,” said Seren, “but if you prefer to dance with Rapunzel rather than stay down here with me, go ahead. I’ll just wait for you.” He sat down and folded his arms.

Clarissa felt bewildered. “I thought you loved to dance. I thought you were looking forward to dancing with us. It’s an amazing practice to share, and I wanted to show you …”

“I do like to dance, I just don’t feel like it tonight. I wanted to do something quieter, something for just us two. I’ve been working on my Yule stories and songs as a surprise. I thought you’d be pleased.”

“I am pleased,” she said, distressed. “Thank you! It’s just Rapunzel and I made plans, too, and I thought you wanted to join us.”

“Do whatever you want,” he said. “I’ll wait until you can spare time for me. Go dance, by all means.”

Clarissa looked at Rapunzel, hoping for support. Rapunzel met her eyes. “It’s up to you,” she said. “What would you like to do?”

Please you both, thought Clarissa. Make you both happy.

“I’m going to go up and light the candles,” said Rapunzel. She climbed up the stairs and out of sight.

Clarissa knelt at Seren’s feet. His folded arms shut her out, and she reached for his hands, which he unwillingly allowed her to take. “Don’t be angry,” she pleaded. “We’ve only just found each other, and we’ll have all the time together we want. Nobody will ever mean more to me than you. But I love Rapunzel, too, and she’s counting on me tonight. Dancing is an important ritual for us.”

“Well, I’m so sorry to let you down,” Seren said irritably. “It’s your ritual, not mine.”

“You haven’t let me down. You couldn’t let me down. I was wrong to assume you’d be interested in joining us. I should have asked what you wanted to do. It doesn’t matter, though, because I can do both. I’ll go up and dance with Rapunzel and then come down and be with you. I’m going to sleep here tonight, so we can spend all night together if you want.”

Seren looked away. “I’m weary, and by the time you’re ready to hear me play I’ll be wearier still. I don’t think you appreciate how much of myself I put into performing, even if it’s just for one person.”

“I know. And I do appreciate how hard you work and how much your art takes from you. If you like, after you sing and play for me, I’ll work on your neck and shoulders, help you relax so you sleep well. Remember when your hands were tired after playing and I rubbed them with birch oil? I could do that again.”

His expression softened. “Yes, that did feel good. I suppose I can sleep a bit while I wait for you. After all, you girls don’t need much time to dance.”

Clarissa abandoned a post dance ritual she’d created with a traditional yule log made out of driftwood and candles without a second thought, and resolutely pushed away the anticipation of sitting with Rapunzel in the candlelit tower room, shaping the power raised by their dance into prayers and chants to send out into the dark night for new beginnings and the light’s return. Seren was her mate and her partner. It was her business to ensure he felt like the priority he was. She could no longer act like a selfish child. Now she was loved, her loyalty and allegiance essential in supporting one of the greatest artists in the world.

“You rest, and I’ll be back down before you know it. I can hardly wait to hear your Yule stories and songs! I’ll look forward to it while I’m dancing.”

Clarissa made sure he was comfortable with pillows and a hot drink at his elbow, built up the fire so he needn’t disturb himself, and slipped up the stairs, feeling guilty for keeping Rapunzel waiting.

In the candlelit storeroom, Rapunzel beat gently on her drums. Her hands and fingers dripped with blue violet light, the spirit candles that appeared every time they danced in the tower. Tonight, the lights gleamed like a handful of blue sparks around the candles.

Clarissa swallowed her anxious apology to Rapunzel, took a deep breath and relaxed, realizing only then her tension. Rapunzel was clearly not anxious or in any way waiting. Clarissa knew she could sit for an hour communing quietly with a drumbeat, sunk deep in a meditative state. Rapunzel’s face looked smooth and peaceful. The drumming was reassuring and grounded, the room serene and beautiful in its simplicity of stone, wood, flame and candle.

For a shameful and fleeting moment Clarissa felt glad Seren chose not to join them. She wasn’t sure how to combine her own dance with the complicated dance of relationship, and with Rapunzel she need please nobody but herself.

It was a relief.

She’d laid her dancing clothes ready in a corner. She changed and began stretching and swaying, turning so her skirt flared out, then collapsed smoothly against her legs. Outside the windows snow fell thickly, illuminated by the lighthouse beacon. The tower room was warm, but the stone walls felt cool to the touch. Silver bangles made thin music as they slid on her wrists.

Rapunzel’s drums and Clarissa’s feet spoke to one another in a language of beat and step, and Clarissa turned away from her mind’s chatter and rested in her body. She felt like a half-open flower, not a shy flower like an anemone or a daisy, but an exotic, fleshy blossom, heavy-petalled and intoxicating with scent, nectar and pollen. Seren’s kiss still sizzled in her nerve endings. Her breasts felt heavier than usual, her nipples more sensitive. She pulled off her tunic and weighed her breasts in her hands as she danced, running her fingers over her ribs, hips and collarbones as Rapunzel’s drumbeat became insistent and voluptuous.

Clarissa let her vision blur until the room filled with a galaxy of warm points of candlelight and blue and violet stars. Rapunzel’s hands rose and fell in a blue mist. She drummed with her whole body, dancing in place, her small bared breasts firm with jutting nipples and a sheen of moisture on her upper lip.

Clarissa danced for Seren, though he wasn’t there to see her. She danced her awakening sexuality, her hungry skin, her fiery lips and her swampy center, swollen and wet with desire. She danced for touch, for texture, for hair and fold and the intimate landscape of bone and flesh. She danced for new beginnings, for light and not light, for long winter nights warmed by bare flesh, the taste of salt and musky scent. She danced for ripening womanhood. She danced for Webbd and Delphinus, for the Star-Bearer and Seed-Bearer and their twins.

Rapunzel quickened her tempo, pounding the drums in a driving, insistent beat. As though in response to Clarissa’s powerful youthful eroticism, she wore her ugly woman face and body, and now the blue light outlined knobby, gnarled hands, thick-fingered and scarred, and the violet jeweled nipples crowned lumpy, misshapen breasts. Snarled hair framed her face, which wore an unholy grin baring discolored teeth. Rapunzel whooped, her hands moving faster and faster, and Clarissa felt the rhythm pick her up and shake her by the scruff of the neck. She whooped too, a sound of defiance and exultance, and her pounding feet echoed the rhythm of Rapunzel’s hands.

Clarissa, at one with the rhythm, lost all sense of time, but eventually the drums stopped driving her and began to hold her, to support her, and her feet slowed and quieted. She wrapped her arms around herself and felt the muscles in her back and hips move under damp skin. The candles melted and dripped, leaving wax pooled and puddled on the rocks beneath them. She turned and turned again, her hair swirling around her shoulders, her arms and hands graceful, her breathing quieting. The drumbeat still carried her, lifting and moving her feet gently, but slowing all the time, slowing until her steps were small and sliding and her skirt brushed against her legs as she swayed.

When at last the drums slid away into silence, Clarissa felt a pang of regret. She had been somewhere without time, without constraint or limitation, without effort or fear, and in that place, she felt beautiful, powerful and elemental as the sea. Now she was back, and it was surely getting late, and her lover waited while she danced in heedless ecstasy.

Rapunzel had reclaimed her true visage. She left the drums and moved about the storeroom, stretching her shoulders, hands and fingers and twirling in slow circles as though to an internal melody.

Clarissa looked out a window and saw nothing but falling snow, eerily lit. She thought longingly of the stove, the sheepskins, the pillows and Seren, waiting for her below. Her body sang, warm and alive, humid and supple.

Rapunzel tossed a couple of cushions on the wood floor and she and Clarissa sat. Ginger, Persephone and Rapunzel had taught Clarissa to linger in the space of dance for a time, basking in the power they raised and the intimacy of the practice. It served the dancers to slowly find their way back to spoken language and their everyday lives together, rather than attempt an abrupt transition.

Clarissa controlled her impatience to rejoin Seren and tried to sit quietly, but tension hardened her shoulders and neck.

Rapunzel watched her. “I’m glad you joined me,” she said.

“I’m sorry about Seren,” said Clarissa. “I shouldn’t have assumed he was joining us.”

“Not everyone is a dancer,” said Rapunzel.

“Oh, I’m sure he’s a dancer! He’s often talked about dancing. He didn’t feel like it tonight, I guess. Rapunzel, I made a Yule log and brought it up, but Seren’s waiting for me, so I’ll let you do that part alone. Do you mind?”

“I don’t mind,” said Rapunzel. “Do you?”

“A little, but I know I’m selfish. Seren’s plans are as important as mine are, and I promised I’d go down to him as soon as I could.”

“Go, then. Enjoy yourself. I won’t be down again tonight.”

Clarissa met Rapunzel’s eyes. “Thank you,” she said gratefully.

As Clarissa came down the stairs into the living area, she found Seren sitting with his lyre in his lap, fingering the strings as though in casual conversation with the instrument. He glanced up at her briefly, but didn’t mention her dancing skirt and tunic or notice the silver bangles on her slim wrists. She felt as brilliant and palpitating as a star and was sure she looked her best, but some of her confidence seeped away as he looked aside and said, “At last. I thought you were never coming.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “I came as quick as I could.” She set aside a small bottle containing birch and almond oil. Moving swiftly, she lit the candles, put wood in the stove and blew out the lamp, intending to honor both light and darkness and create serene, sensual atmosphere. The body’s language needed no light.

“What are you doing? How will you be able to see me perform if you blow out the lamp? The candles are too dim.”

Feeling guilty, she hurriedly re-lit the lamp. Clearly, he felt rejected and betrayed, especially after the kiss they’d shared. Now she must do everything possible to earn his trust again. In the generosity of her love and admiration, Seren would forget his hurt and kiss her again, but this time they wouldn’t be muffled to the ears in a storm. The whole long night stretched before them, but she would need to give as well as take.

“How’s this?” she asked Seren, setting the lamp so it illuminated the spot where he liked to stand while he performed.

“It’s fine, I suppose,” he said. “Are you ready now?”

“I’m ready. Where would you like me to sit?”

“Sit here, at my feet, and look up at me. I play my best with you there, and you can watch my face and hands.”

She settled herself on the floor, smoothing her skirt against her legs. She looked up into his face and said, “This is what I’ve been waiting for!”

To her relief, he smiled back, his face warming.

As he played and sang, his face intent in the warm lamplight, she tried to concentrate on his stories and songs. She was developing a reverence for story, avidly collecting them wherever she could, and now her own notes grew nearly as extensive as her father’s, because Seren knew such a treasure trove of new material. Seren discouraged her from creating her own versions of traditional material, especially anything he used in his repertoire, because it would be disloyal and foolish to compete with him, but Rapunzel freely gave her permission to tell any of her stories. Clarissa noted the bare outlines of the traditional stories, songs and poems in her growing collection, just for the pleasure of preserving them.

However, on this night her body, fully awakened by the dance and Seren’s kiss, distracted her from listening. Her eyes drank in the sight of his face, his mobile mouth, his fleeting expressions as he sang and spoke, the silvery glow of his eyes as his gaze met hers. She imagined herself in the lyre’s place, spread across his lap, his hands fingering, plucking, strumming her flesh, and flushed with desire.

When the last notes and words died away, she felt as though she woke from some kind of trance. She searched for words to convey her admiration and reassure him of his place in her life. Moved by the beauty of this shortest day, the storm, the kiss, the dance and now this man, tears rose in her eyes and overflowed down her cheeks.

No words could have pleased him more. He caught a tear on his finger. “Tears for beauty, or tears for woe, little one?”

“Tears for your beauty,” she assured him. She laid her face against his knee and he stroked her dance-disheveled hair. His touch was mesmerizing, and she would have happily stayed like that the rest of the night, but he stopped stroking, gave her a pat and moved restlessly. At once, she lifted her head and clambered to her feet.

“I brought the birch oil down,” she said. “Would you like me to work on your muscles? It’s warm here by the stove.”

“If you like,” he said.

“May I blow out the lamp now? I don’t need it to work on you.”

“Yes, blow it out.”

“If you’ll take off your shirt and lie down on your stomach, I can get to your back.” She found a clean towel, picked up the birch oil and knelt beside him as he lay on a sheepskin.

He lay with his face turned away from her. She hadn’t seen him without a shirt before, except briefly on the day he’d staggered out of the sea, and his back, pale and fine-grained, broad at the shoulders and tapering towards his hips, lay exposed before her, bisected by the delicate ridge of his spine.

Clarissa pulled off her tunic and set it aside, along with her silver bracelets. The oil would stain the fabric, and the wide sleeves would be in the way. She spread the towel over her lap to protect her skirt, shook the oil mixture into her palm and rubbed her hands together to warm them. The sharp, astringent scent of birch mingled with the warm air. Closing her eyes, Clarissa laid her hands gently on Seren’s back.

For the second time that night, she allowed herself to sink into a deep, wordless state of being, the same place from which she danced. Her mind and its chatter became as distant as the dark sea outside the lighthouse, and the language of words sloughed away like a shed snakeskin. Now the language of the body filled the room, filled the night, the language of hair, nerve, cell and muscle fiber, the language of tissue, membrane and bone. Clarissa allowed her hands to fill with desire, longing, moist scent and passion. She warmed the oils in her palm and disclosed her love with touch, stroking and smoothing first and gradually increasing the pressure. His flesh softened and relaxed as she worked, his muscles flattening and warming into smooth sheets rather than ropes. His skin absorbed the oils, wakening into supple sensitivity. Her strong fingers probed his neck and shoulders; she discovered every tension point and released it.

As in dance, she lost the sense of time. She knew only the tingling scent of birch, the stove’s warmth and the wordless conversation between their two bodies, the question and answer of her flesh and his, the eroticism of silent unrestrained discovery. Her hands buzzed and tingled with heat as she poured herself into communicating her love, her reverence, her desire, through touch. She swayed above him, her bare breasts heavy and aching to brush against him, and imagined his excitement if she allowed her hair to brush his skin, or her nipples to graze him.

But no. This touch was for him, freely given. She must give before receiving. She must be worthy, for he was a great man, a great artist, and to him she was still only a girl of no special talent and mixed parentage. He didn’t yet know what she was capable of. This touch was her offering, her demonstration of passion and sensuality, her assurance that she was a worthy mate and companion.

When he understood he would roll over and pull her down next to him, claiming her, welcoming her, and together they would explore the body’s language and limits.

She worked until he felt as warm and relaxed as a sun-soaked cat. Her own hands ached and her shoulders felt tense from effort. She corked the bottle and rubbed the excess oil off his back and her hands with the towel.

He groaned with pleasure, turned his head to look at her, and said, “That felt marvelous. I don’t think I can move. I don’t think I want to move.”

She laughed with pleasure. “Don’t, then. I’ll put the oil in the kitchen. Shall we let the candles burn or blow them out?”

“Might as well blow them out. I don’t need them while I’m sleeping. Are you going out, or do you want to sleep upstairs in my bed tonight?”

She had been in the act of pulling off her skirt. She stopped. “I’m sleeping here tonight, remember?”

“Oh, that’s right. You can use my bed, but be sure you don’t get oil in it, will you? And will you pull a blanket over me before you go? Thanks. I hope Rapunzel doesn’t come down too early. I could sleep for a week.” He turned on his side, pulling a pillow into place under his head.

Clarissa pulled her skirt back into place and reached for her tunic. Suddenly she felt cold all the way to her bones. Cold, worn out, and as wooden and aching as though she hadn’t danced in weeks. She made her way through the firelit room to the stairs. Seren already breathed deeply and contentedly in sleep. The room smelled of birch oil and extinguished candles.

She took off her skirt and tunic without lighting a lamp. Seren’s unmade bed felt cold and unwelcoming. She searched his pillow for his scent, but the strong smell of birch oil from her hands overwhelmed subtler aromas. She lay awake for a long time, trying to warm up. When she finally turned on her side, pulling the quilts closely around her, the pillow beneath her cheek was sodden.

CHAPTER 10

ROSE RED

Rose Red missed Eurydice. She hadn’t realized how much she counted on the fellowship of another woman who lived on the community’s edges rather than within it. Eurydice’s role as gatekeeper, and her own role as protector of the forest, meant they stood like bridges between Rowan Tree and the wider world. With the portal no longer open and Eurydice’s absence, Rose Red felt the full weight of maintaining connection between the people and the rest of Webbd; every day her confidence weakened along with the oak tree.

After the Rusalka left she made a real effort to spend more time with the community. She ate a meal in the hall at least once a day, and made it a point to visit Maria, Ginger and Kunik frequently.

After a long and busy harvest season, Rowan Tree settled in for winter. They culled the domestic animal population for meat, leaving only breeding stock. The root cellar was full and stacked firewood leaned against walls and filled sheds and empty animal pens. Outside work ended for the season. Now their energy went into fireside tasks such as spinning, weaving, working with leather and skins, and carving. Stories and songs were shared, and those who could play an instrument sweetened the dark hours of evening. Yule, the longest night, approached.

On a late morning of iron sky and bitter wind, Artemis appeared at Rose Red’s door. She shivered, and Rose Red realized she’d never before seen Artemis affected by temperature or weather. She wore a deerskin tunic and leggings and short leather boots, with a cloak and hood in the coldest weather, but Rose Red hadn’t seen the cloak she now appeared in. When Artemis threw back her hood, Rose Red saw a lining of coarse-haired, cream-colored pelt.

Rose Red put her in a chair close to the fire and heated water for tea. Artemis leaned toward the flames, rubbing her hands together, the cloak still draped around her shoulders. She wore her thick hair short, and with a pang Rose Red noticed grey in it.

She’d never thought of Artemis as aging. She seemed eternally youthful, both in looks and lithe strength and endurance. Mistress of Animals, Protector of Wilderness, it was inconceivable she would age and weaken and, perhaps, one day, die. The thought made Rose Red feel cold. One by one, the most important people in her life seemed to be leaving.

She made tea, and at the same time put soup on to heat. Artemis looked as though she needed it.

She handed a steaming cup to Artemis, who gratefully wrapped her fingers around it, before sitting with her own cup. “Are you warming up?”

“Yes. It’s one of those days that’s far colder than snow. I’m glad to be here. I wanted to see you.”

“Is everything all right?” Rose Red asked, feeling childishly fearful. “I mean, everything’s not all right. I know that. But do you bring bad news?”

“I bring news. It sounds as though you have some, too.”

“You go first.”

Artemis sipped her tea, which contained a good slug of Gabriel’s mead, sweet and heady.

“Mmm,” she said with appreciation. “This is wonderful. Just right on a day like today.”

“Gabriel makes mead every year.”

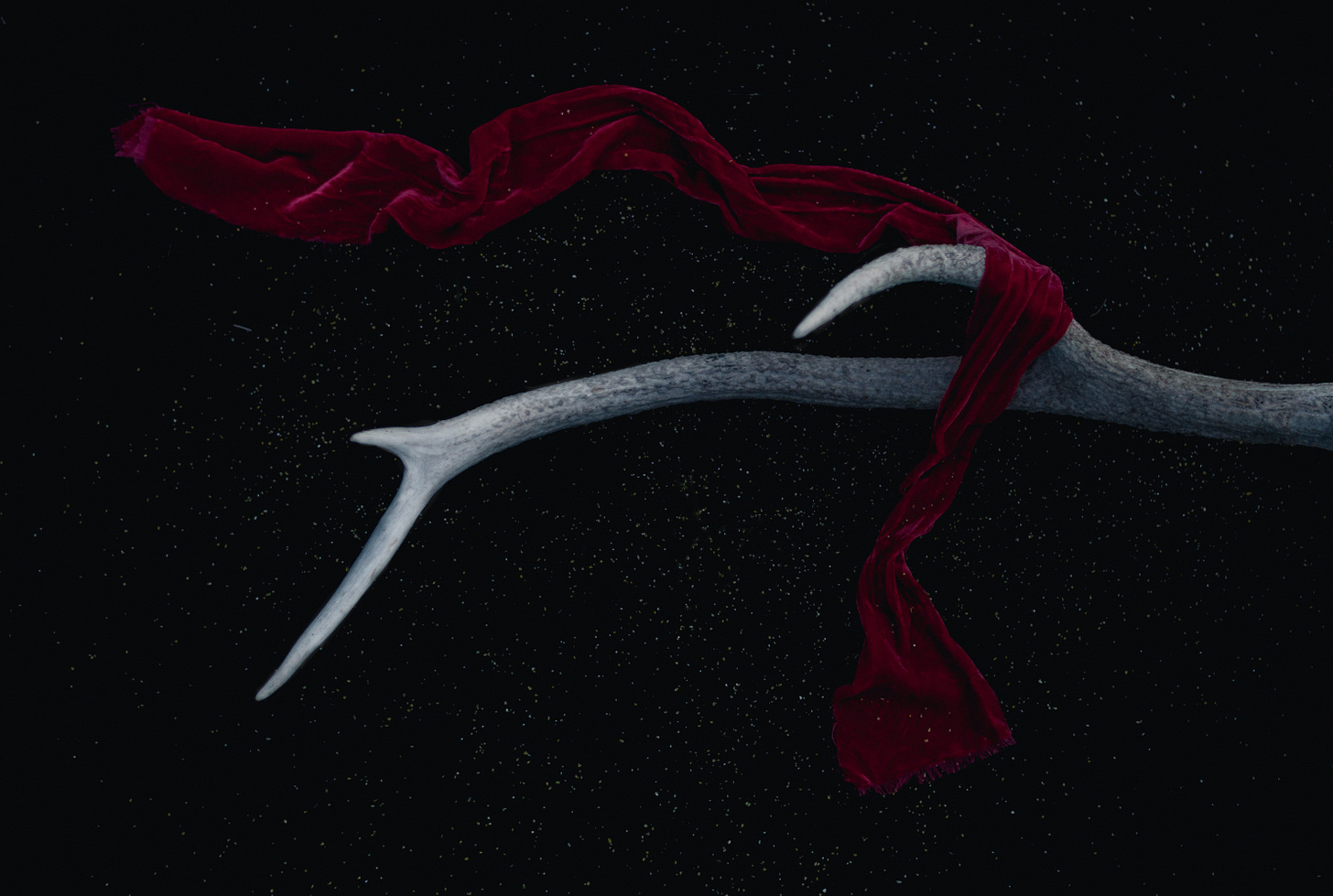

“Good for him.” She set the cup down on the hearth. “Rosie, the White Stag is dead.”

Rose Red heard, but couldn’t understand.

“What?”

“The White Stag is dead,” said Artemis clearly and slowly, holding her gaze. “He’s gone. This is made from …him.” She turned back an edge of her cloak and ran her fingers over the white pelt.

“But…how?”

“He sacrificed himself at a Samhain ritual. I was there, and Baba Yaga, and Hecate. Odin and Death were there, and Rumpelstiltskin. Morfran and Vasilisa participated, as well as the Rusalka, and Heks, Eurydice and Persephone.”

“Eurydice? But she and Heks left for Yggdrasil weeks ago!”

First, they traveled to Baba Yaga’s birch forest. From there they traveled to Yggdrasil with Rumpelstiltskin. They successfully helped the Norns, and they’re on their way back here now, except for Rumpelstiltskin, who’s spending some time with his people.

“I can’t believe it,” said Rose Red blankly. “I thought the White Stag was eternal.”

“Yes and no. His true name was Cerunmos. He was the Horned God. The Horned God is eternal, but he doesn’t always inhabit the same body. The White Stag was a shapeshifter. He could take a man’s shape. He was my sacred consort, and we worked together for many years, but Cerunmos is always sacrificed in the end, and he and I both knew the sacrifice would come one day.” She looked away from Rose Red, into the fire, her face bleak.

Dead. The White Stag was dead. Rose Red sipped her tea, feeling numb. The hot liquid burned the roof of her mouth. She set it down carefully, folded her hands together in her lap, and studied them. Without warning, tears fell down her cheeks. Dead. As though her tears dissolved some kind of armor, then she did feel. The White Stag, that kingly, stately creature with his glowing coat and big, dark eyes, was dead. He had comforted her, walked beside her, been there during every difficult moment of breaking away from her parents and finding her place in the world. He was gone. Forever gone. She wouldn’t see him again. And if she grieved, how much more must Artemis grieve?

She wiped her streaming eyes and nose ineffectively. “Oh, Artemis, I’m so sorry. I don’t know what to say.”

Artemis shook her head wordlessly, and Rose Red realized she too wept. She wondered if Artemis had mourned with anyone since the ritual, or if she’d been alone, traveling through bony forests and frostbitten hills.

Tears for the White Stag and Artemis became tears for her parents, whom she loved but felt unwanted by; Rowan; her oak tree; the loss of the Rusalka, and Eurydice’s absence. For a few moments Rose Red gave herself up to grief and fear, finding comfort in the presence of another woman’s tears.

“Everything is changing,” she said when they were quieter. “There’s so much loss and uncertainty. I’m afraid of what’s coming next.”

“Change is hard,” said Artemis. She drained her cup. “I feel uncertain and frightened, too. I’m also weary. I can’t protect the wild by myself. Cerunmos was more than a lover. He was my mate, and our roles required we work together.”

“What about us -- all your handmaidens?”

“You are each essential,” said Artemis, “but a sacred pair is required, a balance of male and female energy. The forests, the hills, the animals -- they all depend on that balance. People speak of me as the virgin goddess, the chaste protector, because I control my own sexuality, but I’m neither virgin nor chaste. Nothing is more powerful than union arising from commitment and consent between male and female. It fuels the very roots of life. I have honored that power with my body and my choices, as did Cerunmos.”

“What will you do now?” asked Rose Red.

“I’m not sure. I haven’t thought much past coming to tell you. I suppose I ought to visit my other handmaidens and spread the word that the White Stag is gone, but this isn’t the time of year to travel, especially alone.”

“Stay here with us,” Rose Red urged. “Spend the winter and set out in the spring.”

“Perhaps,” said Artemis. “You’ve heard my news now. What’s yours?”

“I don’t know where to start,” said Rose Red.

“Start with what you wept for.”

Encouraged by Artemis’s loss and her unapologetic frankness regarding her relationship with the White Stag, Rose Red told her about Rowan, from the first time she’d met him on a night she and Artemis woke the trees to the last time she’d seen him. Although several of her friends understood she and Rowan were lovers, she hadn’t fully revealed their history or her experience of the relationship before, partly out of innate shyness and delicacy and partly out of shame that an animal had such power to rouse her passion.

“I didn’t think we’d stay together always,” she said. “I understood he was a wild animal. He could take a human shape, but even then, he was all fox. The truth is when we first came here, I felt lonely for a human mate, a man who could help me plan and build. Rowan saw no need for either, and felt no interest in the future. He hunted, ate, slept and mated as naturally and thoughtlessly as any other animal. When I was with him, there was nothing but now, nothing but flesh and scent and passion. He didn’t feel embarrassed or ashamed or self-conscious, and I do all the time. He freed something in me, and with him I became a different person. With him I became as wild and primal as he. It scared me, but I also love that part of myself -- the part that responded to him.”

“He was exactly the right lover for you,” said Artemis. “You’ll remember what he taught you, and you won’t be satisfied with anyone who’s unable to rouse the same passion in you.”

“But we weren’t a sacred pair, like you and Cerunmos,” said Rose Red. “We had no commitments to one another.”

“And now you’re both free to go forward with what you taught one another,” said Artemis, and Rose Red felt comforted.

The conversation moved on to the oak tree, the Rusalka’s revelations about mother trees and their departure, Eurydice’s observations and fears about Rowan Portal, and the community’s small doings.

After a bowl of soup and a fresh pot of tea, Artemis related the events of the Samhain ritual and what she knew of Eurydice, Heks and Rumpelstiltskin’s travels. While in Baba Yaga’s birch woods, she had talked at length with the Rusalka, and learned for the first time of Yrtym. She too had noted the dullness of the falling leaves and dead and dying trees. Autumn had brought heavy winds, and weakened trees fell by the dozens, blocking paths and lying down swathes of forest.

“I wanted to tell you about the White Stag before Heks and Eurydice did,” she said to Rose Red. “I also want to hear what they found at Yggdrasil and how it is with the Norns. I’ll stay at least until they return. We need information, but information will be harder to share if the portals break down. I know the birch wood portal and the one here are affected, but there are others connecting one place and people and another.”

“Have you heard anything from Gwelda?” asked Rose Red. “I thought about trying to get a message to her. She and Jan will certainly notice problems with the trees, and they may have heard other news.”

“That’s a good idea,” said Artemis. “I haven’t heard anything from her.”

“I’ve sent Rowan with a message for her before,” said Rose Red, “but I don’t expect to see him again.”

“And I would have asked Cerunmos to go to them,” said Artemis. “We’ll find another way.”

Artemis agreed to stay with Rose Red, and they spent the rest of the day talking. Late in the day the sky became heavy, the air smelling of snow. Snug in Rose Red’s little house, with plenty of food and firewood, they stayed where they were for the evening. After a meal they sat by the fire until Artemis began to nod. She crawled gratefully into Rose Red’s bed. The wind rose outside, and when Rose Red stuck her head out the air was thick with snow. She blew out the lamp and joined Artemis under the quilts and the White Stag’s pelt. Comforted by Artemis’s presence and the cloak’s weight and warmth, she slid into sleep.

The following morning, they woke to drifts of wind-driven snow. Just outside Rose Red’s door the ground was bare, but they waded through hip-high drifts on Rowan’ Tree’s sloping hill to reach the community hall. Smoke rose from chimneys and several bundled figures with brooms and shovels worked, clearing paths to the animals, the root cellar and the large communal building, where breakfast no doubt cooked.

“We have a couple of new people,” Rose Red said to Artemis as they labored through the drifts. The wind had diminished, but the air felt icy. “They both turned up recently and asked if they could spend the winter with us. One is called Chattan. He hasn’t said much about how he came here, but he stayed with Kunik when he first appeared and Kunik is impressed with him. He knows a lot about living off the land and is willing to do any kind of work. He’s quite strong. There he is, see?” she indicated a figure shoveling a path to the goats with powerful thrusts.

“The other man is called Mingan. He was the second to arrive. He came with news of trouble. Fighting and conflict in his old home drove him out. He says people are behaving unnaturally and turning against their own kind. He asked Maria to let him stay here, at least for the winter.”

After brushing the snow off one another with a broom outside the community center door, the two women entered into the warmth and scent of frying meat and toasting bread. Maria worked in the kitchen, along with several other women. Two young girls watched a baby lying on a blanket on the floor near the fire. Artemis was greeted warmly but without fuss, and she and Rose Red joined in the cheerful chaos of a snowy morning requiring cooperative effort.

As food was ready, those present sat down to eat, and gradually those working outside made their way in to warm up and dry off. By that time, Rose Red and Artemis had enjoyed a hearty breakfast and Rose Red was washing dishes.

Artemis made no mention of the White Stag. She was introduced to Chattan and Mingan when they appeared, faces red with cold. She moved from the kitchen to the gathering space near the fire to the long dining tables, talking to everyone at least briefly. Somewhat to Rose Red’s surprise, she greeted Heks with an embrace. Heks, making no concessions to old womanhood, had been out wielding a broom with the men and seeing to Maria’s chickens.

Rose Red, watching from the sink, recalled Heks had attended the Samhain ritual in which the White Stag was sacrificed. She understood the bond shared ritual created, as she and Kunik had been through an Ostara ritual together. Aside from Eurydice, he was her closest friend at Rowan Tree. He’d been one of the last to come in, and he sat eating with Chattan and talking to Artemis.

“Rosie.”

Rose Red swam up out of deep sleep. She lay on her side, back-to-back with Artemis. The fire had burned down to a glow.

“Mmm?” she said.

“Listen.”

Rose Red, trying to wake herself enough to listen properly rather than fall back asleep, turned on her back and folded down the quilts, letting cooler air stroke her body. She lay still, listening hard.

“There,” said Artemis quietly. From somewhere in the dark winter woods came a low, wailing cry followed by desolate sobbing, as though the winter forest itself wept for the end of warmth and light. It raised the hair on the back of Rose Red’s neck.

“It’s not the trees, is it?” she asked confusedly.

“No. It’s moving closer.”

It was. The sobbing trailed away to a moan, and now Rose Red thought she could hear something huge and heavy moving in the dark. Weeks ago, a freak wind storm had knocked down hundreds of trees which, in addition to the recent heavy snow and drifts, made travel in the forest difficult, even in daylight. Whatever approached moved steadily though, breath coming in sobs, and Rose Red could hear heavy objects being shifted as the footsteps drew inexorably closer. Was it moving fallen trees out of its way?

Something nudged at the back of her mind, some memory of a time she’d heard something large moving through the trees before. Not a bad memory, a good one.

“It’s not an animal,” whispered Artemis. “Too big.”

“Yes,” breathed Rose Red in agreement.

“Rosie?” the thing outside said. “Oh, Rosie, I need help!” The words trailed away into sobbing. At the sound of the voice, Rose Red leapt out of bed and flung the door wide.

“Gwelda! Is that you? Artemis, make a light, will you? Gwelda?”

Lamp in hand, freezing in bare feet and nightgown, her gaze traveled from a pair of leather boots, each the size of a sled and lined with fur, up legs like tree trunks swathed in yards and yards of green canvas that reminded Rose Red of a tent, and a thick leather belt. The light provided by the lamp in her hand illuminated no higher. With a “whump!” the figure sat down in the snow and she recognized her friend Gwelda, a giantess who, with her human husband, Jan, planted and harvested trees and assisted Artemis in protecting the wild forests. What appeared to be a large, heavy blanket was pinned at her throat like a cloak, and a clumsily knit scarf of pink and orange swathed her head and neck. On one hand she wore an immense hide mitten. A dirty white cloth with an end dangling wound around the other hand.

At the sight of Rose Red, Artemis at her shoulder, Gwelda’s green eyes overflowed with tears. They fell down her cheeks and added another layer of ice to the scarf, crusted from her condensed breath and previous tears.

“He’s dead! They’ve killed Jan …burned the house…” She rocked back and forth, sobbing.

With great presence of mind, Artemis dressed and built up the fire. She poured what remained of Rose Red’s mead into a large bowl.

“Gwelda, drink this. We must get you warmed up. Here, let me pull this off for you.” Artemis tugged at the mitten, which slid off, revealing rabbit skin lining. Gwelda’s fingers looked red and stiff, and Artemis rubbed them briskly. “Get dressed, Rosie. It’s too cold to stand here without clothes on.”

Rose Red dressed hastily while Artemis coaxed Gwelda to take the mead. Rose Red longed to bring the giantess inside, put her in a chair in front of the fire and feed her, but she couldn’t possibly fit in the house, or in any building at Rowan Tree. She and her husband visited in fine weather, when they could live outside. And now Jan was dead, Jan with his humor and his sharp axe and devotion to Gwelda. Who could possibly want to kill Jan?

In the end, Gwelda sat as close to the open door as possible and Rose Red stoked the fire until it roared. She and Artemis felt quite comfortable and Gwelda’s front, at least, warmed. She unwound her scarf, revealing disheveled hair, fading purple in color and showing an inch of brown at the roots, and they hung the scarf near the fire to dry. As they tended her, Gwelda sat passively, tears continuing to stream down her face, though she stopped sobbing.

Rose Red thought she looked dreadful. Her eyes were red-rimmed and swollen, her lips cracked, and she looked as though she hadn’t slept in days. The unraveling bandage around her left hand concealed an angry-looking burn, blistered and oozing. Rose Red didn’t know what to do with it, so she tore up a linen sheet for a clean dressing. In the morning, she would consult Maria about how to treat such an injury. Gwelda mopped her eyes, blew her nose, accepted a towel wrung out in warm water and wiped her face.

“Thank you,” she said, handing the towel back to Artemis. “I’m sorry to get you up in the middle of the night. I didn’t know where else to go…” her lip trembled.

“Of course you’d come to friends when you were in trouble,” said Rose Red. “Where else? I’m only sorry we can’t do much for you until morning.”

“You were here,” said Gwelda. “That’s what I need more than anything.”

“Can you tell us what happened?” Artemis asked.

Gwelda heaved a sigh, running her uninjured hand through her lank hair. “I don’t know what happened,” she said. “I mean, I know what happened, but not how or why or who. Jan and I noticed something wrong with the trees this fall. Healthy trees are dying, and they all appear to be weakening. A tremendous wind blew a few weeks ago, and it knocked down hundreds of trees.”

“It happened here, too,” said Rose Red.

“Well, we’ve been worried, and Jan began to travel more, trying to understand what was wrong. Since he wasn’t working as much as information gathering, I stayed at home. I’ve traveled, too, but I can go a lot farther in a day than he can, so I’ve been returning home for the nights.”

“What did he discover?” asked Artemis.

“Not much. Nobody seems to know what’s happening, but he heard reports of trouble everywhere. It’s not just the trees, either. Jan noticed people seem less friendly and are surly and suspicious, though we’re well known and have generally felt welcomed wherever we went. He couldn’t understand it. The buildings we helped with are sturdy and strong, and the trees we’ve planted are growing. We’ve done nothing to give offense to anyone, just harvested wood, planted new trees and tried to help where we could.”

“What did you find?” asked Rose Red.

“I avoided towns and villages and went into forests and mountains,” Gwelda replied. “I wanted to see if the trouble with the trees was just local or more widespread. We thought perhaps there was some kind of disease at work in the trees and its effects were limited.”

“It’s everywhere, I’m afraid,” said Artemis.

“That’s what I found, too,” said Gwelda. “Everywhere I went, it was the same thing. The Mother trees are the most affected but smaller trees are dying by the hundreds, or already dead. It frightens me.”

“Me, too,” said Rose Red.